Join us in July at the National Shared Mobility Summit — a month of virtual sessions on one topic: THE BIG SHIFT. Our existing physical, social, economic, technological and institutional infrastructure overwhelmingly favor private car ownership and private car use. This year, we ask, “How might we shift the the whole system!” Register now and save 25 percent with code BIGSHIFT21.

The installation of new protected infrastructure for bicyclists does not cause the displacement of people of color or of low-income residents of U.S. cities, a new study finds — but that doesn’t mean transportation leaders always do a good job of advancing comprehensive mobility justice for underserved groups when they improve cycling infrastructure.

In what is perhaps the most comprehensive longitudinal study on the topic to date, researchers at the University of New Mexico and the University of Colorado Denver analyzed socioeconomic and demographic changes in predominantly residential neighborhoods in 29 cities across America that had made investments into bike facilities between 2000 and 2019.

Unlike previous analyses, the researchers painstakingly scrutinized thousands of satellite images on Google Earth to catalogue exactly what kinds of cycling infrastructure each city had installed and when, offering a more insightful glimpse into the displacement impacts of different forms of investment into sustainable transportation than offered by previous researchers. (The study surveyed some of that research its literature review section, including papers that explored some of the more qualitative aspects of gentrification other than simple displacement; be sure to click through to read it.)

What they found may surprise advocates: aside from statistically insignificant decreases in the rates of new rich and White residents moving into neighborhoods with new bike facilities, there was no correlation between the installation of new bike facilities and major shifts in the socioeconomic makeup of those neighborhoods.

Or to put it more simply: bike lanes, trails, and even sharrows were not found to be associated with residential displacement, either along racial or economic lines.

Of course, displacement rates are far from the only measure of mobility justice, and study co-author Nick Ferenchak was careful to note that the finding did not mean that U.S. transportation planners are necessarily doing a great job at using cycling as a tool for broader mobility justice. In particular, the data revealed that transportation leaders aren’t delivering equal access to new bicycle infrastructure for people of color — and in the context of a quantitative analysis, they couldn’t determine whether transportation leaders were delivering equitable access to the transportation infrastructure for which those communities are actually asking, if leaders are even asking at all.

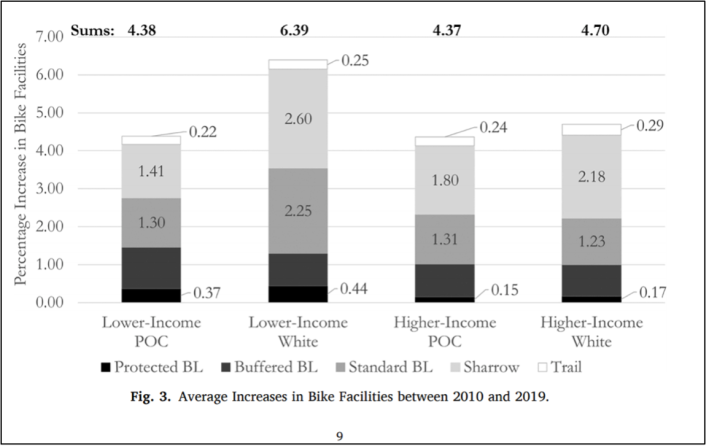

“When we’re looking at overall bike facilities, people of color are getting the lowest rates of bike facility installation,” said Ferenchak. “But, collectively, lower-income people [of all races] see the highest rates. The big question still hanging in the air is, does the supply we’re seeing in these various neighborhoods actually meet the demand of those residents? Could it be that less bike facilities are exactly what some of these neighborhoods want? Are [BIPOC communities] being meaningfully involved in the transportation planning process? There are definitely still mobility justice issues we need to consider.”

But even with those critical questions still unresolved, the study offers some surprising insights that complicate common narratives about how bike infrastructure is distributed throughout U.S. communities.

Earlier studies have shown that White neighborhoods receive disproportionately high percentages of bike facilities, but researchers have tended to calculate based on all bike facilities, such as bicycle parking and painted lanes, neither of which physically protect riders from potential car crashes. Much of the “infrastructure” built in White neighborhoods throughout the study period was nothing more than sharrows, which Ferenchak and his research partner, Wesley E. Marshall, proved have no impact on road user safety half a decade ago.

“We hear cities say all the time that they’ve got 1,000 miles of bike lanes, but when you look at it more closely, they’ve actually got 999 miles of sharrows,” laughed Ferenchak. “When we remove sharrows from the equation and just look at bike lanes, the numbers are much more even [between rates of new facility installation in White and BIPOC neighborhoods.]”

Low-income people, meanwhile, are getting better access to meaningful bicycle infrastructure than some may expect — though maybe not as fast as those communities actually need.

The percentage increase in new facilities on low-income blocks was slightly higher than on richer blocks, but “slight” probably isn’t good enough when you consider that 39 percent of bike commuting is done by the lowest-income quartile in the U.S. On the other hand, the researchers also found that "a rise in income in a neighborhood led to the installation of bike facilities more so than increases in White populations led to more bicycling facility installations."

That finding could mean that wealthy cyclists move into neighborhoods that lack bike infrastructure and then leverage their privilege to get it, while the poorer cyclists struggle to either move to bike-lane-rich areas or get lanes built where they already live — an inversion of a common assumption in the perennial chicken-or-the-egg debate over whether bike lanes attract rich, White cyclists or vice-versa.

Still, Ferenchak and Marshall are hopeful that the insights in their study could at least put to rest one of the most pervasive fears in advocacy: that new bike lanes are a guaranteed sign that the most vulnerable are about to be forced out.

“There’s at least a bit of a green light to cities,” said Ferenchak. “Yes, we have mobility justice issues in our neighborhoods that we need to address, and gentrification is a complex set of forces that goes beyond displacement. But if displacement is our primary concern, yeah, we can go ahead and build the bike lanes. We know we’re not going to be displacing people just by doing that."