Most people might not usually think of public space as being gendered, but this is how scholars of the built environment increasingly talk about it. In many countries, the architecture profession is largely male and white. That results in a design approach that privileges the male perspective, from licensing regimes that favor heterosexual male drinking establishments to parks and sports facilities built for boys.

These assumptions about who the built environment should serve, as well as others such as the heterosexual, family-oriented nature of suburbia, contribute to how it is designed. They can also affect how public spaces are experienced by women or men who don’t conform to masculine stereotypes.

Design failures, such as inadequate or poorly positioned lighting, only serve to make public space even more intimidating for marginalised groups who, as a result, try to make themselves invisible – or avoid open spaces altogether.

In the context of rising patterns of hate crime, the idea of “queering” public space might offer a solution. Through interviews with over 120 academics, designers, activists and other respondents, we have studied how considering the design and planning needs of LGBTQ+ people might make the public realm more inclusive.

Marginalized geographies

Since the 1980s, scholars have mapped out geographies of how different social groups access, or are marginalized and threatened, in public space. Much has been written, in particular, about the emergence of the “gayborhood”. From the 1950s, queer urban enclaves – such as Manchester’s Gay Village and London’s Soho – began to appear in run-down, marginal areas of cities across the world. Key initial factors were low rents, good transport links and accessible bars and other amenities.

These neighborhoods, however, are not without problems. Improvements led to increases in rent, so that these enclaves steadily became overly structured around relatively wealthy gay white males. Poorer LGBTQ+ people can often only access them via potentially dangerous transport networks. What’s more, as is borne out by police statistics, gayborhoods like Soho are marked by relatively high levels of homophobic crime.

These areas are also vulnerable to redevelopment. By contributing to the cultural value of a city, gayborhoods eventually attract investors. But regeneration and gentrification often results in the communities who used to visit or live in these areas being displaced. Almost 60% of London’s LGBTQ+ venues have closed since 2010.

So, while gayborhoods have provided much appreciated space in which LGBTQ+ people can be themselves, we still need to think about inclusion in public space more generally.

Inclusive design guidelines

In the UK, existing guidelines for inclusive design concentrate largely on accessibility for disabled people. In our research, we have identified three main principles to improve this.

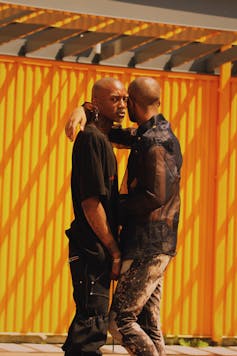

First, planning regimes should prioritize safety. LGBTQ+ people need more privacy in public space because common activities that most people take for granted (holding hands, with a partner, say) can draw negative attention.

Our respondents highlighted how greenery and lighting could be used to break up space and sight lines and provide more privacy. It’s about getting away from both claustrophobic, enclosed designs and large, open plazas dominated by the kind of harsh security lighting and wide sight lines dictated by surveillance strategies, and the protection of property.

Instead, as in New York, planners can follow the gender-sensitive approach pioneered in Vienna, Austria, to make city parks and streets feel safer and more comfortable on an individual level.

There they have installed better, warmer lighting to encourage footfall (which can help to counter hate crime) and created semi-enclosed pockets in parks that are visible but still offer a reasonable level of privacy for those who do not feel comfortable being visible from all angles and from far off.

Second, city planners need to cater to the specific needs of all sectors of the population. For the LGBTQ+ community, this does not just mean preserving venues and historic landmarks. Historically, housing has often been intentionally designed for heterosexual families. Changing design assumptions – planning for all kinds of people and families - will make cities and neighborhoods feel more accessible and diverse.

The distinctive services required by an aging LGBTQ+ population also need to be considered. This group is more likely to live alone than their peers. They often have distinct health needs and can lack support networks. Crucially, their experience of discrimination and exclusion often means they prefer to live in queer-specific accommodations.

Third, planners need to make spaces visibly inclusive. More representation of queer heritage – through statues, memorials, plaques and street and building names – would emphasize that these communities, though marginalized, have always existed. And making that history more visible, even temporarily, may help to undermine public hostility towards them.

Similarly, as on the South Bank in London, features including public artworks, artistic lighting or decorative street furniture, such as rainbow crossings, can help to signal inclusion to LGBTQ+ people.

It may seem that these recommendations are simply about general good public space design. And they are. Addressing these design issues would benefit all sections of the community, rather than just LGBTQ+ people by making public space safer, accessible and inclusive for all.![]()

Pippa Catterall is a professor of history and policy at the University of Westminster.Ammar Azzouz is a short-term research associate at the University of Oxford.

This article is republished from The Conversation with permission. Read the original article here.