The American Southwest may have experienced one of the biggest bike booms in the world in 2020 — and the rest of the country wasn’t far behind, a new study finds.

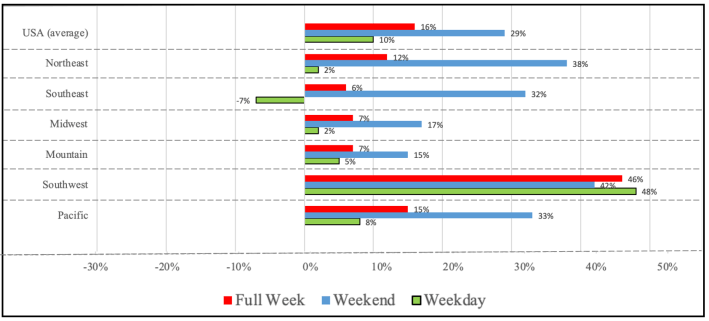

In a paper published in the latest issue of Transport Reviews, researchers compiled and analyzed data from thousands of bike counters, anonymized cell phone GPS records, and information from city departments of transportation to create perhaps the most comprehensive picture yet of cycling trends during the COVID-19 era. Just as countless researchers (and customers at sold-out bike shops) have found, the number of distinct cycling trips spiked during the lockdowns, averaging 16 percent more total journeys in 2020 than there were during 2019 nationwide.

But when researchers segmented the data by day of the week, they found that the average increase in the weekend cycling was almost double the full-week average. And in the Southwest, cycling surged all week long, including a stunning 48-percent increase over the weekend and a 42-percent increase during the traditional workweek.

The only U.S. region to show a cycling decline during any point of the week was the Southeast, which includes nine of the 10 most dangerous metros for non-drivers. States like Florida, Georgia and Mississippi collectively experienced a 7-percent drop-off in weekday bike commuting — but they also showed a colossal 32-percent increase on the weekends.

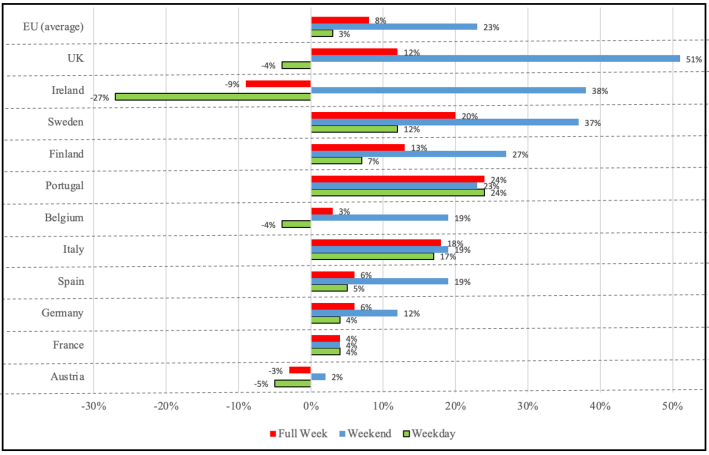

That surge may be even more impressive when compared with other countries across Europe and Canada. The only nation that experienced a bigger weekend bike spike than the American Southwest was the United Kingdom, which had 51 percent more weekend bike rides than the year prior.

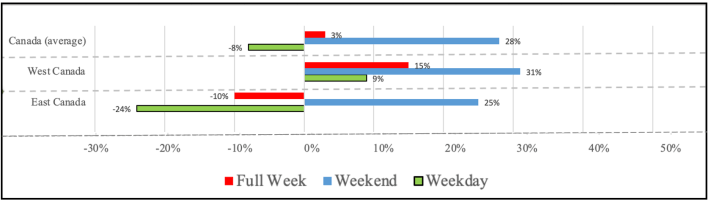

But during the week, the Brits actually rode 4 percent less than they did in 2019. That may be, in part, because of the rise of remote work; about 6 percent of UK workers commuted by cycle before the pandemic, or about 10 times the rate of U.S. workers. But by most measures, the desert states still had a bigger cycling surge overall.

Canada, where 7 percent of workers commuted to work by bike prior to the pandemic, experienced a similar phenomenon, posting a 28-percent weekend increase and an 8-percent weekday decline.

The researchers say the U.S. data, in particular, underscores something that was painfully obvious to safe street advocates long before the pandemic: that car dominance on our roadways is the biggest deterrent to active transportation.

“The experience of traffic danger is the biggest threat to people who want to continue bicycling after the pandemic,” said Ralph Buehler, a professor of urban affairs and planning at Virginia Tech and one of the co-authors of the paper. “Now, we need to keep the [car-light] places we’ve created, and expand them if we want people to continue to ride.”

But comparing U.S. bike stats with European data may be instructive to American advocates in other ways, too. Buehler, who is himself a native of Germany, said that European countries’ anemic cycling increases may actually be a testament to those nations’ pre-pandemic success at encouraging active transportation, which meant their cycling populations didn’t have as much room to grow. (Severe lockdowns in many EU countries that temporarily banned biking for exercise probably had an impact, too).

“In a lot of German cities, they don’t just get around by bike; deliver mail by bike, police on bikes — they do everything by bike, across all demographic groups,” said study co-author John Pucher, a professor emeritus at Rutgers, who once lived in Deutschland himself. “The only three large cities in Germany where cycling fell were bike-oriented university towns, because students transitioned to remote learning and they didn’t go much of anywhere by bike, car, or transit. There’s so much we can learn from other countries about how to encourage people to ride.”

Many U.S. communities, of course, took nearly unprecedented steps to make active transportation safer during the pandemic — at least when considered relative to the virtually total inaction that characterized their approach before. The researchers suspect that pandemic-prompted pop-up bike accommodations throughout the U.S. had a dramatic effect on the overall numbers.

“COVID made it politically and publicly passable for hundreds and hundreds of cities to restrict car use,” said Pucher. “Whole systems of open streets, pop-up bike lanes, reduced speed limits — and all these extraordinary things happened. It made cycling more comfortable and convenient, and I think that’s part of why people showed up.”

Those same programs, of course, have rightly faced criticism, in part for failing to center the needs of BIPOC, essential workers, and other groups who are less likely to have access to a car. Buehler and Pucher say there’s vanishingly little data about the demographics of the cyclists who populated U.S. roads during the pandemic, but their literature review did suggest that many new riders took to bikes for stress relief and mental health (58%), exercise and physical fitness (57%), or simply socializing with friends and family (43 percent), rather than to reach a workplace or essential service. (Survey respondents were invited to select multiple motivations for riding, but transportation did not make the top five.)

Still, the researchers are hopeful that the people who tried out cycling last year will ride again — and if cities create low-stress spaces for them without the assist of a global lockdown forcing drivers to stay home, maybe next time, they’ll even replace a car trip with a cycling trip.

“It doesn’t really matter why they started riding, because if they are out there riding now, they may consider the bicycle as a mode of transportation for other trips,” said Buehler. “Before the crisis, a lot of Americans may not have ever thought of riding their bike because they were afraid of traffic, or because the bike was rusting away at the back of the garage. But if they had a good experience on these pop-up bike lanes, they may consider the bike for trips in the future to go to the café, to the movie theater, to work.”