Across the country, city transportation planners are stymied by two fundamental problems: how to map the most dangerous segments of their local road networks, and how to calculate exactly how many lives and public dollars could be saved by simply re-designing them. Now, a potentially groundbreaking new tool could help give them both elusive pieces of information with the click of a single button.

But some professionals are wary of the company who made it: one of America's largest automakers.

Last week, Windsor, Canada became the first North American city to start using the Ford Safety Insights Platform (yes, that Ford; no, not that Insight), a traffic safety analysis tool that proponents claim could help solve two of the most enduring problems in transportation planning: identifying the most dangerous intersections with ease, and making the case to local officials that redesigning them makes safety and business sense.

The former problem, in particular, has long been a thorn in the side of Vision Zero advocates and safety-minded transportation planners alike.

At a state and regional level, car crash reports are notoriously inconsistent, with each municipality collecting a unique set of data about incidents of road violence that might differ drastically from reports collected by neighboring departments. Some law enforcement bodies even deliberately instruct officers not to report on crashes that don't involve significant property damage — which means that countless pedestrian and bicyclist crashes, in particular, are left out the reports that planners rely on to make safety recommendations. And even the most detailed crash reporting standards are still subject to the discretion of individual officers, who might fail to report key details of a crash at all.

"In past work I did in Buncombe County, N.C., we found that nine in 10 bicyclist crashes and three in 10 pedestrian crashes went unreported, meaning they didn't show up in the state's crash database taken from police reports," said Don Kostelec, a planner who's worked with departments of transportation across the country. "For example, if you or I run our car off the road and into a ditch, it is a reportable crash that goes into a crash database that engineers use to help define project investments to address safety concerns. If I run my bike into the same ditch for the same reasons, it is not a reportable crash. "

And then, of course, there's the far stickier problem of how to identify dangerous intersections in which relatively few crashes might occur, but terrifying near-misses happen every day. A recent study of traffic camera data found that a high concentration of narrowly avoided car crashes were among the strongest predictors of future incidents of traffic violence, but few cities have access to the type of continuous, anonymized footage necessary to spot potential tragedies before they happen — and without that data, they can't be proactive about stopping them.

Ford Safety Insights seeks to address those shortcomings in a straightforward way: by aggregating as much available data about a city's road network as possible, and then using artificial intelligence to isolate all the traffic violence hot spots at lightning speed. That dataset doesn't only include those imperfect crash reports; it also includes information from any "smart" traffic lights or other digitally connected infrastructure that a city might happen to have, and of course, anonymized data from late-model Ford vehicles themselves.

That might not seem like a huge cache of information, but the company emphasizes that the "millions" of newer Ford vehicles on the road are more than enough to provide a meaningful snapshot of traffic violence trends — and that the anonymized data they provide might be a crucial missing piece of the Vision Zero puzzle.

"Crash data has a lot of limitations — and connected vehicle data also has some limitations, but it has its own benefits," said Cal Coplai, who leads the project. "[Connected vehicle data] can tell you not just where cars tend to strike another car, but also where drivers tend to speed a lot, or where there are a ton of hard-braking events. ... It can be updated much more frequently, and you’re getting potentially a bigger amount of events — and a more complete picture of your roadways."

Coplai is himself a planner and a former data analyst for the city of Kalamazoo, and says his team sought to build a tool that's useful for safety-minded professionals like him. Safety Insights was also inspired, in part, by a U.S. Department of Transportation competition that offered a $350,000 prize for the best data visualization tool to improve road user safety. (Safety Insights made it to the final stages of the competition.)

"That was a recognition from the US DOT that there's a bit of a gap in the traffic safety space," said Coplai. "There's so much data emerging from connected vehicles, smart traffic signals, and all these other inputs, but what we don't have are a lot of tools to help people access and make sense of that data."

But there's another gap in the traffic safety space that may be even harder to fill: what to do with all that data to actually save road users' lives.

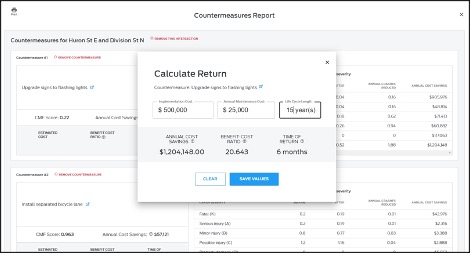

Ford's answer to that question is, basically, to provide planners with a list of common countermeasures to their most persistent problems — say, installing a flashing pedestrian beacon at a segment of road where walkers are frequently hit — and then using industry-standard formulas to automatically estimate the potential cost savings of that countermeasure over time. (The same software will even estimate how many human lives might likely be saved by a particular bit of good road design — though Coplai is smart to recognize that, depressingly, the human argument alone isn't always enough to get a project funded.)

Safety Insights itself doesn't recommend one redesign over another, but Coplai hopes that it could help planners make the case for good design in dollars and cents.

"From my perspective, there’s no amount of artificial intelligence that could replace a planner or engineer," said Coplai. "But that doesn’t mean that there’s not a role to play for data analysis like this. We’re not reinventing the wheel here; we're relying on best-practice methods to estimate savings for various solutions, and doing it quickly...If a planner wants to implement that solution, it gives him or her a tool to help make the case for it in terms of crash savings and societal costs."

Planners themselves are understandably reluctant to welcome the automaker as an ally in the fight to build safer cities, even if Ford itself has rebranded itself as a full-service mobility company in recent years. Some planners we spoke to for this story were skeptical that Safety Insights' "industry standard" algorithms would adequately emphasize the needs of non-drivers, or adequately account for the less easily quantifiable benefits of making streets safe for people — far beyond the money saved in avoided car crashes.

"Any source of information or analysis from the auto industry is suspect in my mind, especially [given the past] advertising from Ford about 'petextrians' and the histories these companies have in lobbying against the safety and rights of vulnerable road users," Kostelec said. "[But] it could help automate what historically is done through intense academic study."

Ultimately, it will be up to street safety advocates to decide whether they agree — and whether the enormous power of companies like Ford can be harnessed to build a world that's safer for everyone.