Many autonomous vehicle advocates will probably think of 2020 as the year that "driverless" tech got a disappointing reality check. But history might remember it as the year that robocars became a fait accompli — but for safe streets advocates, 2021 must be the year they get put in their proper place: at the bottom of our transportation hierarchy.

To hear most media pundits tell it, robocars have had a wild ride in 2020 — and arguably, a fall from grace. Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao kicked off January at a splashy consumer electronics show in Las Vegas, where she announced a new set of regulatory "guidelines" that essentially gave the industry an enthusiastic thumbs up to test the nascent technology on American streets with only voluntary, self-administered safety assessments.

But despite Chao sending them off to the races — and a global pandemic that many experts initially thought would speed the advent of driverless delivery — AV companies sputtered. By late April, industry insiders were confiding that the economic downturn coupled with delays in crucial on-road testing could push back the commercial debut of autonomous vehicles on our roads by four to six years; by December, e-taxi giant Uber had foisted its notorious AV division off onto start-up Aurora after reportedly losing hundreds of millions of dollars developing the technology.

It was only the latest in the wave of consolidations in an industry whose leading experts once estimated that there would be 10 million fully self-driving cars on our roads by the end of this year. Instead, there are zero.

Uber was supposed to turn a profitable quarter this year, but that's since been pushed back to sometime next year. So Uber selling its AV division, clearly comes in pursuit of that goal. Thing is, it hasn't handed over control entirely.

— Matthew Beedham (@mattbeedham) December 9, 2020

But there's another way to tell the story of the autonomous vehicle industry in 2020: as the year the industry planted the seeds for what could be a dramatic and potentially dangerous reshaping of American streets.

Just before the pandemic struck, Chao's DOT made good on its promise to greenlight as much AV development as possible by allowing delivery company Nuro to begin testing the first delivery vehicle without a steering wheel, brake pedals, or crumpling windshield on U.S. roads; this week, Amazon-owned autonomous vehicle company Zoox revealed an eerily similar robo-taxi without any of those safety features, either. Zoox's vehicle will be able to travel a whopping 75 miles per hour when it makes its debut on U.S. roadways.

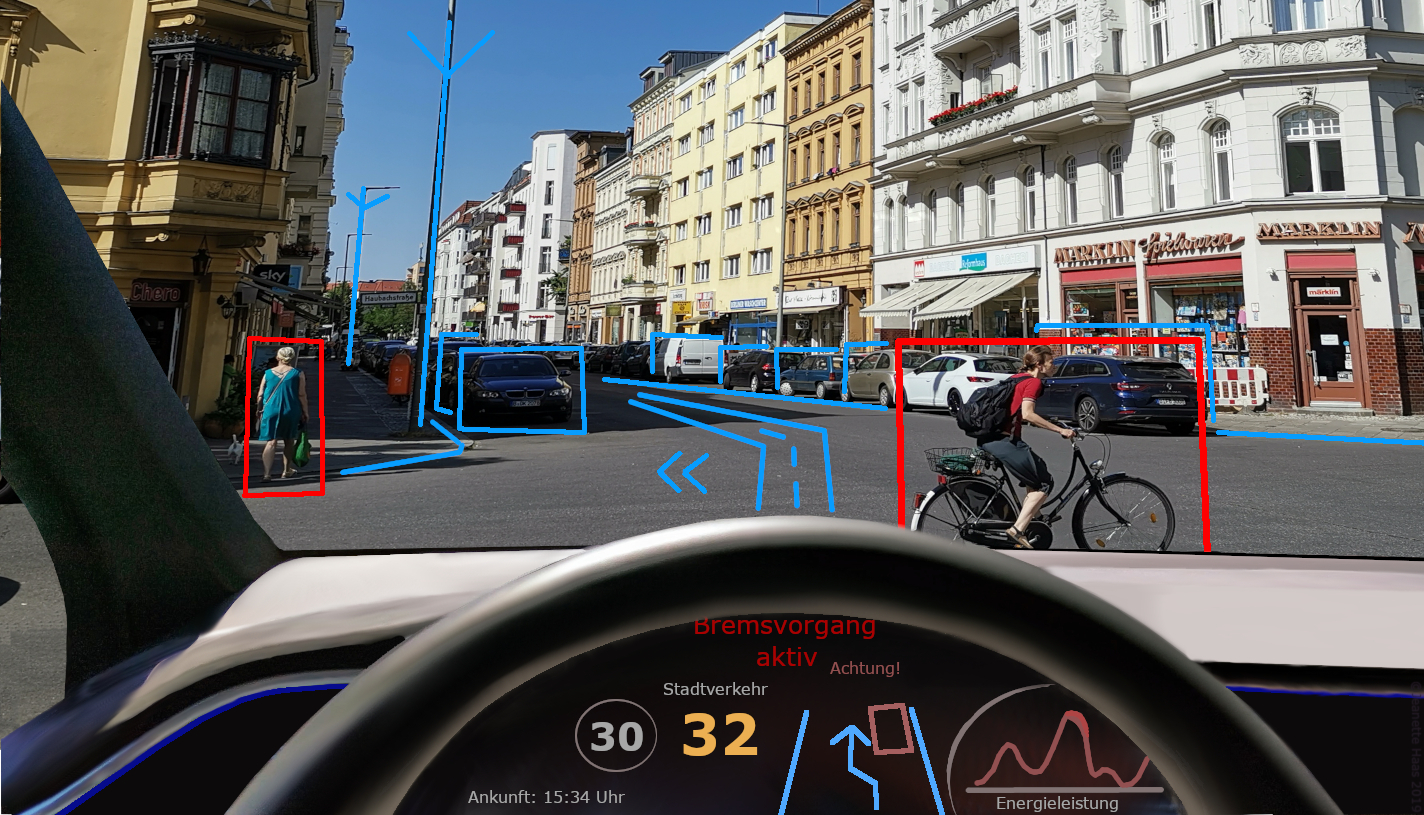

Zoox probably won't reach such deadly speeds immediately, but driverless e-taxi company Cruise is sending autonomous cars capable of high speeds onto the streets of San Francisco now, albeit only in limited nighttime trials and with a human passenger standing by to override the vehicle's autopilot. Unlike Zoox, Cruise's autonomous vehicles do have a steering wheel, brakes, and other basic safety features that a human driver could ostensibly use to take control; still, the company sat its human backstop in the passenger seat with a "kill switch" in his hand instead.

Even Uber's famed exit from the autonomous vehicle space wasn't exactly an indication that the company had given up on its dream of eliminating (already disturbingly low) driver wages from its list of expenses, despite countless headlines that claimed otherwise. Rather than selling off its AV division, the e-taxi giant actually gifted it to startup Aurora, and then invested a further $400 million into the smaller company to speed the development of its vehicle fleet. In the process, CEO Dara Khosrowshahi also joined Aurora's board, functionally guaranteeing that Uber will continue to throw its lobbying dollars towards maintaining lax federal regulations on the new technology. And Uber is not alone: Aurora's other investors include even larger giants like Amazon and Toyota, which are, of course, also invested in a range of other AV-startups that could potentially increase their companies' profit margins if the tech scales.

"Autonomous vehicles were a lot more expensive and complicated to develop than anyone thought they'd be," said Rob Ackerman, a Wyoming-based venture capitalist. "It seems pretty clear that Uber is moving money around on a balance sheet. ... Now that they're a public company, this is a good way for them to reduce risk to their investors by basically outsourcing their research and development to a smaller player. I don't think this move will slow the development of this tech at all."

That's a far cry from 2018, when many speculated that Uber would abandon AVs altogether following the horrific death of pedestrian Elaine Herzberg under the wheels of one of the company's autonomous vehicles. (In another 2020 low point, the human backstop driver who was behind the wheel of Uber's AV at the time of the crash — not the company that supplied her with a dangerous car with multiple disabled safety mechanisms — was charged with Herzberg's death.) And Silicon Valley's paper-shuffling aside, most experts agree that transportation companies will continue to pump money into AV development for one simple reason: they can't afford not to.

Despite classing its employees as contractors to avoid paying towards their healthcare, social security and other basic employer-sponsored protections, e-taxi companies still pay drivers billions every year, which is one reason they're still struggling to turn a profit. Traditional automakers, by contrast, are likely anticipating a day when our inconvenient climate change reality brings about the end of private vehicle ownership as we know it, and are hoping they can at least populate our streets with autonomous, electric e-taxis before our nation gets too comfortable with actually green modes like transit, biking, and walking.

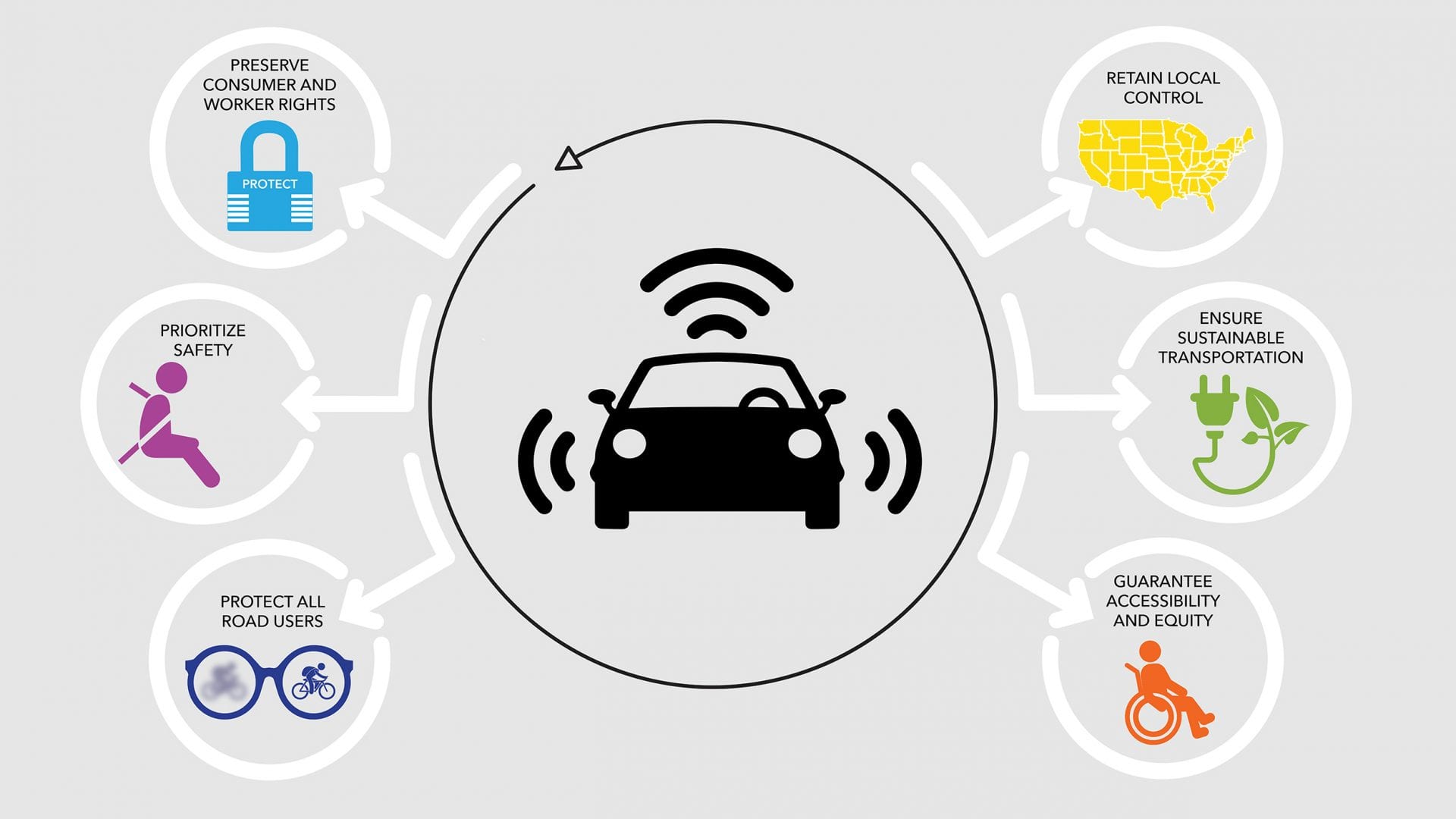

But the AV industry's relentless march to market doesn't necessarily mean that our country is destined to simply trade run-of-the-mill car dependence for autonomous car addiction. Recently, a broad coalition led by the Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety released a list of tenets "to guide federal legislation and policy on the development and deployment of AVs" that the group is hoping the next administration will look to as it, hopefully, rebuilds the regulatory framework surrounding new the new technology. Crucially, the tenets include the preservation of consumer and worker rights, as well as protection for all road users — two things that haven't exactly been a priority in the autonomous vehicle rollout so far.

And ideally, such regulations wouldn't just keep dangerous robocars off the road before they're ready. They'd also prevent American communities from treating autonomy as a silver bullet for road safety — at the expense of a more complex slate of reforms designed to combat car dependence, which has countless noxious effects on society beyond safety and emissions alone.

"Automated vehicles have the potential to decrease transportation emissions — or make them worse," said Scott Goldstein of Transportation for America, which is a member of the coalition. "With thoughtful policy, AVs can serve as an important connection, bridging the gaps in public transit and walking and cycling infrastructure. [But] alternatively, AVs may increase our emissions and worsen congestion by incentivizing sprawling development, further cementing driving as many Americans’ only transportation ‘option.’ We need to ensure that AVs do not incentivize spread-out land use patterns and therefore the development of more communities where it is unsafe or inconvenient to take transit, walk, or bike.”

Of course, some aspects of autonomous vehicle technology can save lives right now — or could, if federal safety standards required automakers to use them. Automatic emergency braking systems, blind spot detection, and lane departure warnings are all proven to help drivers avoid crashes, without providing so much assistance that drivers feel compelled to (literally) fall asleep at the wheel of imperfect autopilot systems.

In 2021, perhaps the most important question about autonomous vehicles is whether we'll pass regulations that put such proven technologies in every new human-operated car we put on the road. And we should also be asking ourselves how we can shape policy next year that puts even perfect autonomous vehicles where they should have been all along: at the very bottom of our roadway hierarchy, reserved exclusively for the people and trips that truly require a car.