Here's a confession that some folks in the Streetsblog audience might be find a little shocking: I own a car.

More specifically, I resentfully maintain an 11-year-old Toyota with fewer than 80,000 miles on it, despite multiple cross-country road trips for various moves in my mid-20s. Outside of long drives like those, that much-neglected Yaris stays parked outside of my St. Louis apartment most days of the week, paint peeling to a leprous patina because it rains a lot here and I never bother to wash it.

It is not an exaggeration to say that I hate pretty much everything about owning a car. I hate the panic attacks I get nearly every time I drive it, I hate the money I have to spend to keep it running, and I hate knowing that every time I turn it on, I am contributing to the not-so-slow demise of the planet, not to mention multiple pandemics that are disproportionately killing my BIPOC neighbors.

But the truth is, sometimes, I need my dumb little Toyota — and if I'm honest, it's not just because I live in an auto-dependent city that thought it was a good idea to ram two highways straight through our core downtown, and put every single doctor's office that takes my insurance umpteen highway miles away.

When the e-bike company Rad Power Bikes offered me the opportunity to try out its relatively inexpensive $1,699 Rad Wagon 4 electric cargo bike, I knew it wouldn't help me surmount some of my biggest day-to-day barriers to biking — and of course, there are enormous barriers that people with fewer privileges than me face every day. No bike, no matter how fancy, can protect a rider from dangerous drivers who are reassured by a raft of legal policies, roadway designs, and our entire culture that if they kill a person outside a car, they will almost certainly face no consequences. An e-bike alone can't put a grocery store within easy reach if your city relegates them to strip malls off of high-speed highways; it also can't prevent gender-based harassment and abuse, or racial profiling and police assault against people of color, or any number of barriers I can't fully comprehend as a white, cisgender person with a host of economic and social privileges.

But there were a handful of barriers to riding that I thought an e-bike might be able to help me overcome, so I could leave my piece of crap Toyota in its city-subsidized parking space just a little more often. Here are a few.

Riding in a mask

Fun fact about me: I have mild asthma. (Fair warning: you're going to hear about some of my various medical conditions throughout this post, because they sometimes impact my mobility, and also, because stigma is stupid.) Because I have the extraordinary privileges of great medical care and the time to get the exercise I need to manage my condition without medication, this is very much not a big deal for me most of the time. But I'd be lying if I said that the first time I tried to get on a manually-powered bike in a mask, I wasn't a little uncomfortable by the end of the two-mile mostly-uphill ride to the grocery store.

Like all e-bikes, the Rad Wagon is powered by a pedal-assist mechanism, which means that when you pedal your bike even just a tiny bit, a motor kicks in to keep the bike moving at a speed of your choice, and when you stop pedaling, the motor stops, too. You do need to keep your feet moving throughout your ride — though the pedal assist goes up to a respectable level 5, at which point you don't need to exert yourself very much at all to maintain the bike's top speed of 20 miles per hour, which is pleasantly zippy without feeling out of control.

(Side note: if you want a workout, or your bike is running out of battery, you can select a lower level of assistance, or ride the Rad Wagon with no pedal assist at all. You can even skip using the bike's thumb throttle feature, which is darn handy for getting a beastly 76.7-pound bike moving from a full stop. Personally, I feel zero shame about using the throttle every single time I hit a stop light, and keeping that sucker on maximum pedal assist at all times.)

Perhaps there is no better endorsement for an e-bike these days than this: with an electric boost, riding a bike in a mask is shockingly easy, even when climbing huge hills. And with enough assist, you won't even break a sweat, much less find yourself sucking wind.

Hills

While we're on the topic of hills: I hate them! And contrary to what you might have heard about the midwest: we've got them!

Case in point: I lived in Santa Fe for years, and thus I regularly and literally dream about eating Hatch green chiles. But the only quick way to get home from the single restaurant in my city that serves even remotely passable New Mexican fare involves summiting a 250-foot hill — and I have to do it after I've eaten my body weight in sopapillas.

That hill was about the only time during my month of e-biking that I felt my quads engage, and they didn't engage much. On a steep incline, the Rad Wagon slows down and taps out at about 15 miles per hour — and if you load the bike down with cargo, it will go a little slower than that — but it will make the climb, no problem.

Ginormous grocery hauls

Until recently, I found it pretty easy to get my household groceries on a standard bike, with the help of a basic rear rack, a couple of cheap panniers, and the willingness to make a smaller run to the store a couple times a week on my lunch break rather than embarking on a gigantic, semi-monthly haul.

Then a little thing called "the coronavirus" happened.

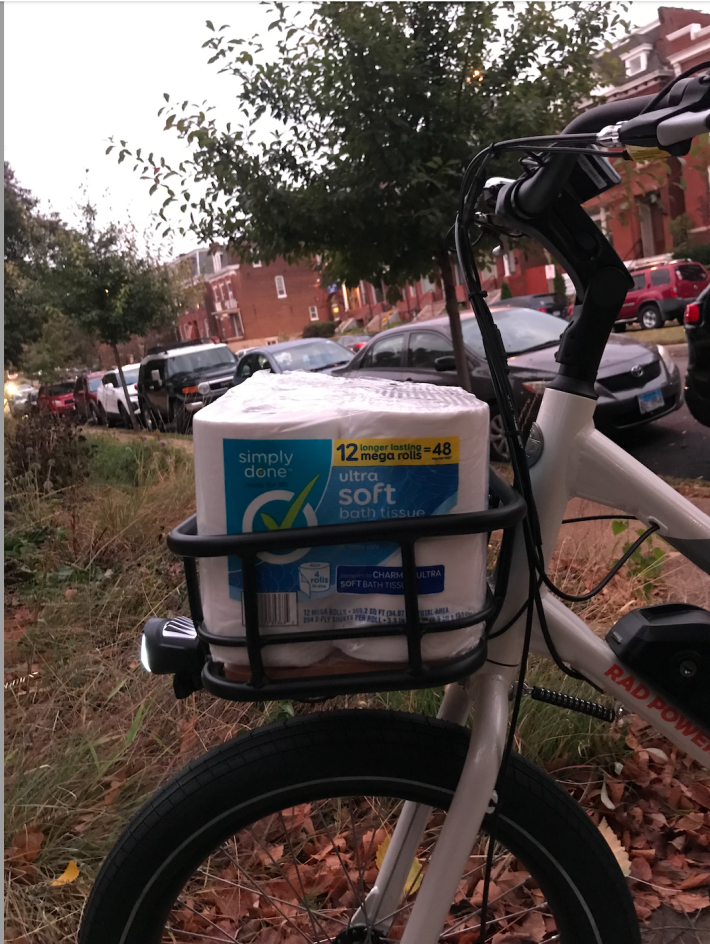

After listening to my friends who live in grocery stores beg everyone they know to stop treating the frozen food aisle like a daily social club, my husband and I cut down to one grocery trip every 20 days or so, and got really good at finding new ways to cook rice. But the trade-off was that we usually had to drive, especially when it came time to re-up on seriously bulky things like toilet paper or a bag of food for our 75-pound dog.

The Radwagon has integrated long-tail rack with a massive, flat platform for strapping down up to 120 pounds of cargo. (The payload for the whole bike is 350 pounds including the weight of the rider; I pushed that rear-loading limit a few times, but, for the record, nothing broke.) With a couple of super-sized Ortliebs, some basic straps and the help of a simple front basket, I was able to haul enough groceries for a whole month — including a month's worth of TP.

Huge stuff

Look: I'm not one of those people who relishes the challenge of hauling every single thing I buy on a bike, no matter how massive it is. If I didn't have my Dumb and Mostly Useless Toyota, I would probably be fine with renting a Zipcar the next time I needed to purchase a big piece of furniture. (Though I stand in awe of Streetsblog Chicago editor Courtney Cobbs, who once managed to haul a full-sized dresser on her Tern.)

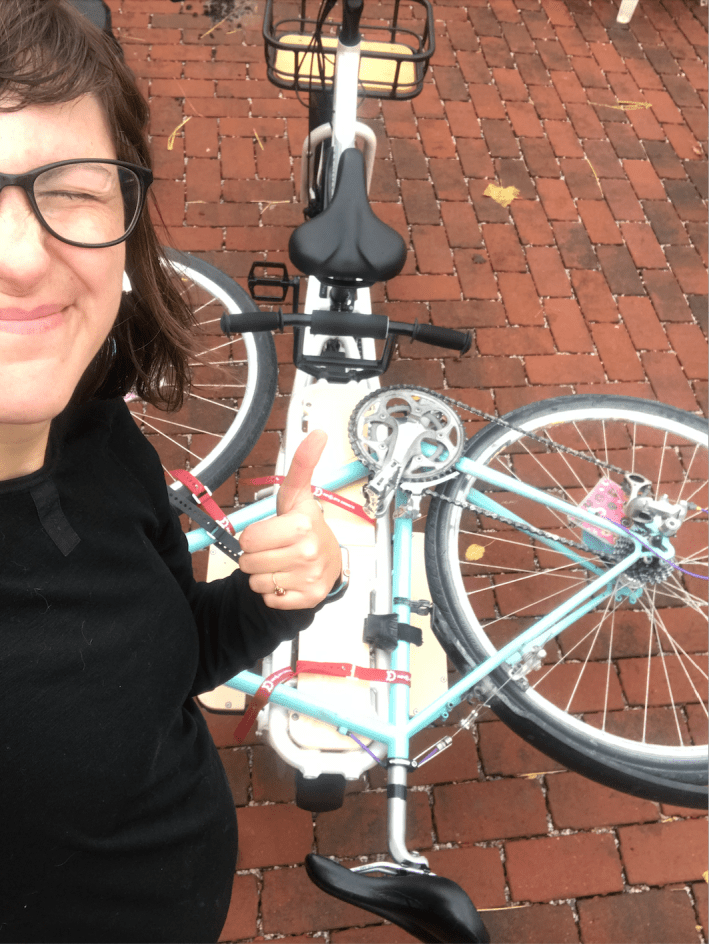

But there is one thing that I've always felt a little cognitive dissonance putting in the trunk of my car, even if I sometimes can't avoid it: my bike. And because there is no local bike shop within walking or bussing distance of my home, every time I shred a sidewall on a tire or otherwise break something on my Surly that I can't or don't want to fix myself, I find myself in the psychically weird position of burning a bunch of fossil fuels to get my favorite people-powered vehicle back in working order.

Well...

Side note: If the RadWagon itself ever became unrideably broken, that beast would definitely not fit on a car rack. But that's what mobile bike shops are for!

When I first got the RadWagon, Rad Power Bikes was kind enough to get my local VeloFix franchise to pre-assemble my bike for me and drop it off at my house, and that gave me an opportunity to meet Francesca, the awesome mechanic who would help me out if I ever got stranded on the side of the road. Since the company keeps prices low by selling directly to consumers rather than to shops — and since many local shops don't work on e-bikes anyway — that's actually how many of their customers get their new rides. (Pro tip if you buy a Rad bike: if you can at all afford it, use a service like this. I'm a firm believer in the idea that no one should need to get certified as a bike mechanic simply to get on two wheels — after all, most drivers never need to learn how to service their own engines — and I'm told assembling an e-bike is a bit of an undertaking.)

Pain

Here's another fun fact about me: like approximately 10 to 20 percent of people with uteruses in the U.S., I have a chronic pain condition called endometriosis. I am privileged to have access great medical care that makes my condition totally manageable most of the time, but I am also unlucky enough to have a severe form of endo that sometimes impacts my mobility. The worst of my condition is intermittent, but I live most of my life with a low buzz of constant pain, and I pretty reliably have a few weeks a year when every individual muscle in my lower back, upper legs and pelvic floor feels like it's being twisted in its own, individual vice grip. On my very worst days, I can't walk more than a few steps without something or someone to lean on, and while riding a bike with a comfy seat and upright handlebars can help a lot, I'm pretty limited to routes without hills that would require me to engage my core muscles very much.

So, yes: endometriosis sucks! But even bad pain days do not make me feel particularly eager to use my Toyota as a the world's largest mobility aid. Hearing from other people with mobility challenges — especially those that are relatively invisible and intermittent like mine — made me curious about trying an e-bike as a possible solution, but cost was always a barrier. (Disclosure: Rad Power let me try the RadWagon for free, but at $1,699, it's easily among the cheapest e-cargo bikes on the market, and some of their other models cost as little as $999.)

Happily (?), I did have one of my nightmarish pain weeks during my 30 days with the Rad Wagon. I used the heck out of that pedal assist, and I even relied on the thumb throttle to propel me for a couple particularly painful blocks rather than moving my feet. I could still feel a little bit of the road vibrating under those teeny little 22-inch tires, and like everything else in my life that week, it hurt. But it hurt a whole lot less than any other bike I've ever tried riding on one of my high-pain days, and it's hard to articulate how freeing it felt to be able to get to the library book drop (mostly) on my own power on a day that I otherwise would have spent curled up in bed.

If there are any health insurers reading: please, please, please make e-bike prescriptions available to people like me.

Passengers

This doesn't need much preamble, so I'll just go ahead and nerd out: with a couple cheap accessories like running boards and some hand grips in the back, you can fit two full-grown adults on a single Rad Wagon. (I'm told you can actually fit three people if two of them are children, but no one would lend me their babies for this story, so you'll just have to trust the Rad Power website on that one.)

Now, lest this article become an ad for Radwagon: this bike definitely has its downsides.

Hauling a heavy, six-and-a-half-foot-long object up the eight stairs to my apartment was not easy or elegant, and on high-pain days, I definitely needed help. I'm not wild about the idea of setting up a ramp every time I need to store my bike, and a water-tight backyard shed is an investment I'm not prepared to make for a single vehicle right now.

The RadWagon's respectable 25-45 mile range also isn't ideal for cargo-intensive activities that I enjoy like like bike camping outside the city, and charging it to full takes a little foresight, since it needs to stay plugged in for about four hours. Knowing I could get home on my own power if my battery ever died was a comfort — and one I wouldn't have with an electric car — but riding the Rad Wagon without a pedal assist would undoubtedly be arduous compared to a lighter standard bike that's built for agility.

Still, despite those small drawbacks, the Rad Wagon easily helped me meet a range of needs that otherwise couldn't be comfortably accomplished on two wheels. Over the course of my 30 day e-bike experiment, I replaced 76 miles of trips that I almost certainly would have driven with electric-assisted bike rides — it probably would have been more, but, y'know, coronavirus — and didn't touch my Dumb and Mostly Useless Toyota once.

I'm not sure I'm quite ready to sell my car yet — St. Louis, build even a single mile of on-street protected bike lane and then maybe we can talk — but it's definitely a start.