Bus ridership had dropped like a stone even before COVID-19 — and if we want to stanch its decline, we need to end public subsidies to car drivers.

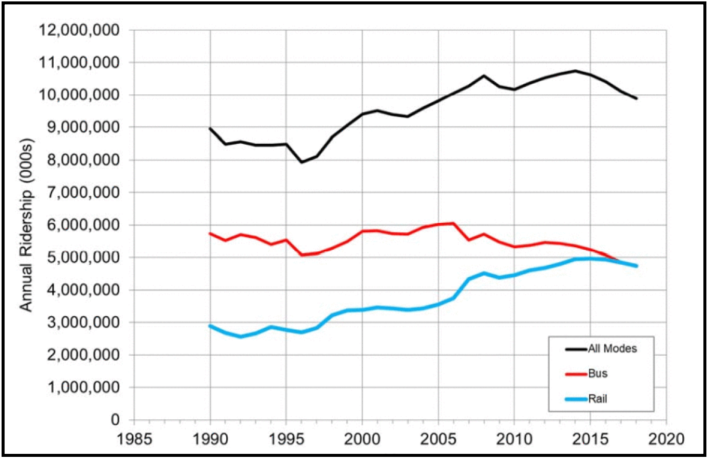

That's the conclusion of a Georgia Tech study that reviewed national bus-ridership data and found that the number of passenger trips declined every year from 2012 to 2018 — reaching its lowest point since 1965. Preliminary data from the American Public Transportation Association suggests the downward trend continued last year. Rail networks also have lost riders since 2016, but not as much as the bus industry.

The drop in ridership comes even though public-transit networks have added miles to their service routes and serve routes more frequently, despite cuts to federal transit funding for three of the five years studied.

The data might seem to indicate that Americans were souring on mass transit — especially buses — long before the coronavirus. But the study's authors concluded that the declines had more to do with the many hidden subsidies America paid drivers during the early to mid 2010s — subsidies that we couldn't afford then and can't now during a pandemic-prompted recession.

Here are three forces driving bus ridership down — and how we can reverse them.

The Rise of Rideshare

Services such as Uber and Lyft have gouged huge holes in transit ridership — and the American taxpayer has helped them do it.

A 2019 study found that bus ridership in San Francisco fell a shocking 12.7 from when Uber entered the market in 2010 and 2018, even when controlling for other possible reasons. In New York City, annual transit ridership fell by almost exactly the same number as e-taxi ridership rose from 2015 through 2018; other cities experienced average bus-ridership declines of 1.7 percent in the year after a macro-mobility app entered the local roadways, and declines continued every year after.

Rideshare's success in snatching riders off of city buses has come at a steep cost to American society. That's because app-taxis maintain their low prices by relying on gig economy labor that offloads the cost of unemployment benefits, healthcare, and even food stamps for their drivers onto the public social safety net. The average gig economy driver’s wages are just $9.21 per hour, with zero benefits. Venture capital backing, meanwhile, further subsidizes the e-taxi industry.

Underfunded transit networks, meanwhile, struggle to meet the complex needs of city residents, even when they offer on-demand services in smaller shared vehicles — because they employ union labor. The worst paid U.S. bus drivers, in Hawaii, make an average of $12.61 an hour plus benefits; the best-paid, in Illinois, make $29 dollars an hour.

The cost of paying union wages, meanwhile, have not been passed along to riders. The average on-demand paratransit trip, for instance, costs a transit agency about $29, but can cost the customer as little as two dollars — a steep loss, but one that the mass-transit industry could afford with robust public investment, which could expand on-demand service to more riders.

Ending subsidies to the rideshare industry by closing gaping loopholes in gig economy employment laws could help fund it — and if states won't do it, our federal government should.

Cheap gas and cheap cars

For almost a century, plunging fossil fuel costs subsidized by taxpayers have depressed transit ridership while boosting the auto industry.

Since 1993, Congress has stubbornly refused to raise the federal gas tax, even as the backlog of highway maintenance (which the tax funds) has worsened. Meanwhile, price wars in oil-producing nations have so cut the price of a gallon of gas that in 2017 it cost less than in did in any year since 1975, when adjusted for inflation — a powerful incentive for Americans to drive private cars. Increasing the gas tax or shifting to a better taxation system could end the massive subsidy to the auto industry and tempt riders back to affordable modes like transit.

We also should reform the lax policies that have allowed a predatory auto lending crisis to grow since the 2008 financial crisis — putting one-time bus riders in vehicles they can't afford.

Trading buses for trains

The Georgia Tech researchers didn't consider whether Americans who abandoned buses boarded trains instead — but if they are, our declining bus ridership may not be so bad.

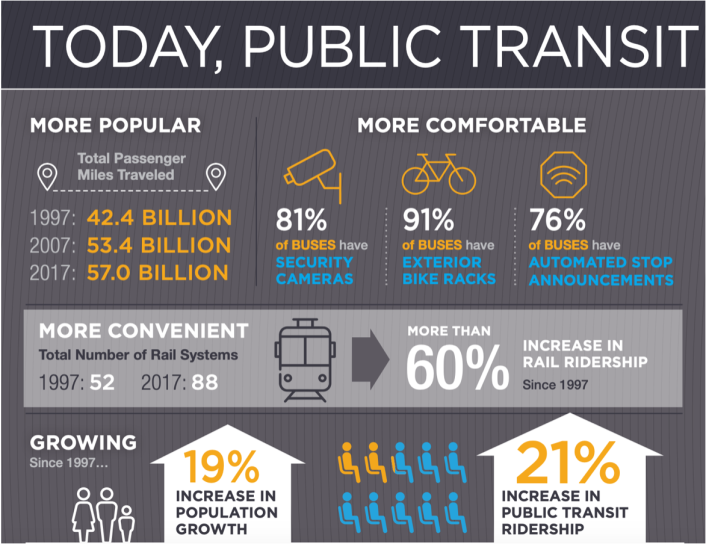

Rail travel declined slightly from 2012 to 2016, but it had risen sharply in the years prior — so much so that trains drove up transit ridership numbers sharply overall. From 1997 to 2017, rail ridership rose 60 percent, and transit ridership outpaced population growth by 2 percent.

That trend suggests that if Americans are souring on bus travel, it may be because cities made good rail investments or rail service changes that better met their needs. In the context of growing driving subsidies and frequent cuts to transit during the study period, it's fairly remarkable that rail networks have kept so many riders — and exciting to imagine how many riders they could gain with better policies.

Of course, because trains and buses are part of the same transit ecosystem, investing in rail doesn't have to mean that bus networks lose riders — or that losing bus riders to train travel is really a loss. The smartest cities often expand bus networks as a prelude to more expensive rail investments, using ridership data on inexpensive bus-rapid-transit routes to help forecast the popularity of proposed train routes. A decline in bus ridership accompanied by a swell in rail ridership could be a healthy signal — and a sign that we should give cities more federal dollars to test bus routes that could lead to more permanent investments.