Only 73 percent of pedestrian master plans even acknowledge the importance of equity considerations in how we build our walking infrastructure — and just 40 percent of plans commit to concrete goals to actually reduce those disparities, a new study finds.

But that same study suggests an intuitive new framework to get those numbers up — and it could be a game-changer for cities who want to create transportation systems that are antiracist, anticlasssist, and all-around better.

In their groundbreaking new paper, Kansas State University-based researchers Amber Berg and Gregory Newmark took a deep dive into 15 pedestrian master plans from major cities across America to understand how some of the largest departments of transportation were — or weren't — centering the needs of marginalized communities in their policies. "Equity" has long been a buzzword in the transportation realm, of course, but there is still no single federal definition of what the word actually means when it comes to pedestrian planning — nor are there many federal requirements for the equitable distribution of key resources and interventions that could save lives on our roads.

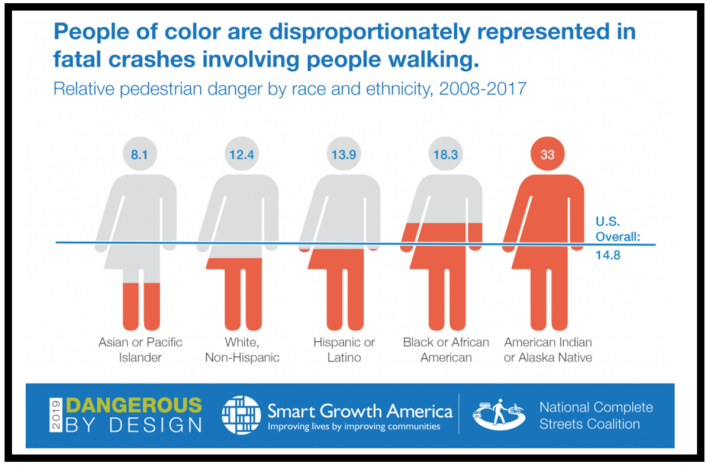

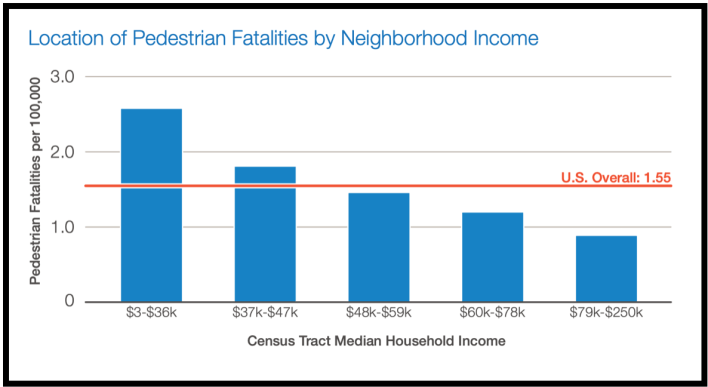

That could help explain why there are still such disturbing disparities when it comes to the safety and convenience of walkers from different racial and socio-economic groups. According to the advocacy group Smart Growth America, walkers who are non-White, elderly, and traveling through low-income communities are disproportionately more likely to be killed by drivers — even after controlling for differences in population size and walking rates.

"I think Amber’s always been acutely sensitive to systematic injustice," said Newmark, who assisted Berg in developing the paper as part of her Master's thesis. "Hopefully, with this framework, planners won't be able to hide behind not knowing what 'equity' really means anymore."

Even among those who bothered to include the word "equity" in their master plans, Berg and Newmark found a wide discrepancy in how our transportation leaders seemed to define the term.

"A lot of cities had what we call a 'horizontal' approach to equity, which is about seeking equity in how things are distributed — they'll might say, for instance, 'we need to build an equal number of crosswalks in each neighborhood this year, and that’s how we’ll achieve equity," Berg says. "But that approach doesn’t address the non-infrastructure-based [barriers], and even the non-physical barriers to walking that are so difficult to overcome in areas with high death rates. Nor does it address what resources some areas might have already had."

A 'vertical' approach to equity, by contrast, might first take a thorough inventory of which neighborhoods already had a lot of crosswalks, and which had none — and do vigorous community engagement around what the residents of underserved areas might need besides crosswalks in order to feel safe on the road, such as taking inter-agency action to end brutality in street policing.

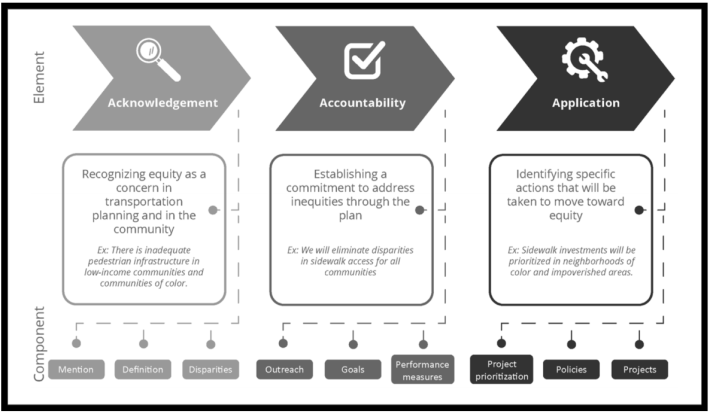

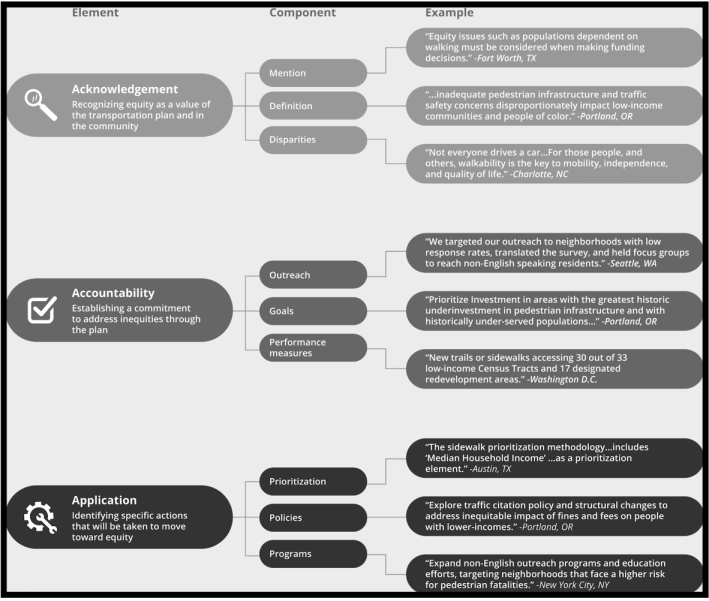

But Berg and Newmark found that even cities with more "vertical" approaches to equity planning weren't necessarily reducing disparities in their equity metrics — and to understand why, they evaluated all the plans through a framework they're calling the "Three A's": Acknowledgment, Accountability, and Application.

An "acknowledgement," as the researchers defined it, is a statement of simple recognition that some specific inequity is a cause for concern in the transportation planning community — and that these disparities deserve the agency's attention and resources to solve. If a master plan acknowledged disproportionate pedestrian death rates in communities of color, that would count as one equity acknowledgement in the researchers' tally; if they also acknowledged that elderly walkers were being struck by drivers at higher rates than young ones, that would count as a second equity acknowledgement.

An "accountability" statement, by contrast, is some concrete commitment to actually address an inequity, such as setting a deadline to achieve Vision Zero, or making putting a promise in writing to increase sidewalk access in underserved areas.

The third A, "application" is where the rubber actually meets the road: a distinct statement where the agency described how it would meet its equity goals. So an agency that promised to improve sidewalk access for pedestrians of color, for instance, would score a point for accountability, but not for application; but if transportation leaders also said they'd actually build sidewalks in certain areas, they'd get another tally mark for putting their money where their mouths were.

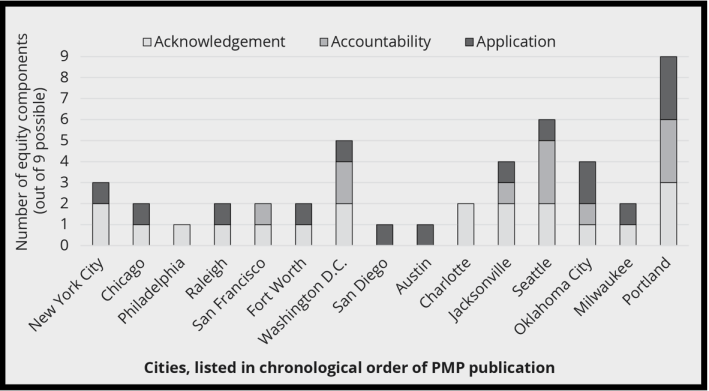

Berg and Newmark combed through the 15 pedestrian master plans in their sample and added up every distinct acknowledgment, accountability statement, and clearly articulated application of an equity solution they could find.

Activist-rich and walk-friendly cities like Portland and Seattle soared on all three metrics. But even some super-walkable and arguably woke places, like New York City, failed to set concrete accountability goals for their plans — and others, like Austin, struggled to articulate why, exactly, increasing equity mattered to their unique place, or to quantify the disparities their programs and policies purportedly sought to solve.

These seemingly subtle differences, the researchers say, can have huge implications for a region's long-term equity efforts.

"Transportation planning that has not set explicit equity goals will not lead to progress in achieving equity, and “socially neutral” approaches to transportation reinforce and may even exacerbate disparities," they wrote.

Still, Berg and Newmark stress that applying the three A's framework is just a place to start — and that every community should do the work of having sustained conversations about what real justice would look like in their unique transportation network. If they don't, the A's could become just another handy list of boxes to check.

"This framework is a great jumping off point, and I really hope that cities implement it so they can be more intentional and more holistic about their plans," said Berg. "However, it’s not the end-all-be-all. I hope that cities are open to the communities that they serve, and continue to add to it and mold it to the needs of their constituents."