As school re-openings loom, the school bus industry is organizing support for the Coronavirus Economic Relief for Transportation Services Act, a $10-billion Senate bill that would provide relief to transportation providers — including school-bus operators — that earlier federal relief packages overlooked.

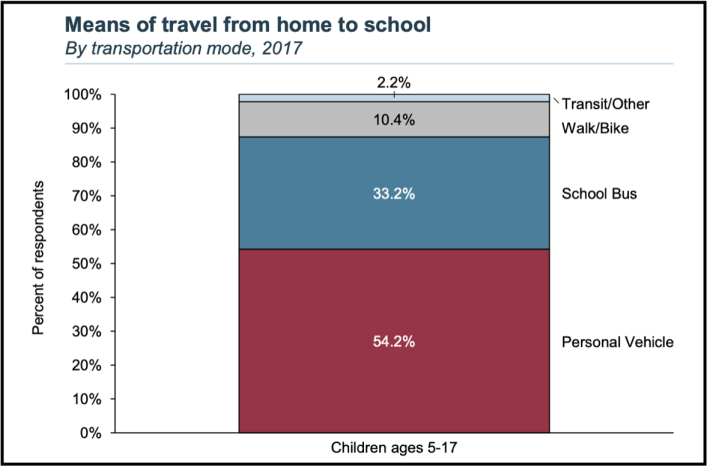

And if CERTS doesn't pass, transit advocates warn that the country is at risk of losing a huge segment of one of the single largest forms of public transportation we have — which would be a disaster for traffic safety and equity, if even a small majority of the 26 million children who take transit every day are forced onto other modes, like cars.

Less than six week before many states have pledged to reopen schools, Senate has yet to approve a new COVID-19 relief package like the Democrats' HEROES bill, which would include funds for K-12 schools to meet the high costs of following new CDC guidelines for cleaning, social distancing, and temperature monitoring in their buildings. Many CDC guidelines also apply to school buses — and guidelines on staggered schedules will add costs for school-transportation providers, too.

And even if the HEROES Act passes, advocates warn that some bus operators would still still be left in the lurch. Because 40 percent of school buses are not owned by school districts, the private contractors who schools rely on need their own financial lifeline — and if they don't get it, they could be facing their second mass unemployment event in less than a year.

"Over the last three months, we've seen tremendous pain on behalf of school-bus workers, through no fault of their own," said Jeff Rosenberg, director of government affairs for the Amalgamated Transit Union, which bills itself as the largest labor union representing transit and allied workers in the U.S. and Canada. "We had 10,000 members laid off in New York City alone in March. And when they got laid off, they not only lost their income; they also lost their healthcare."

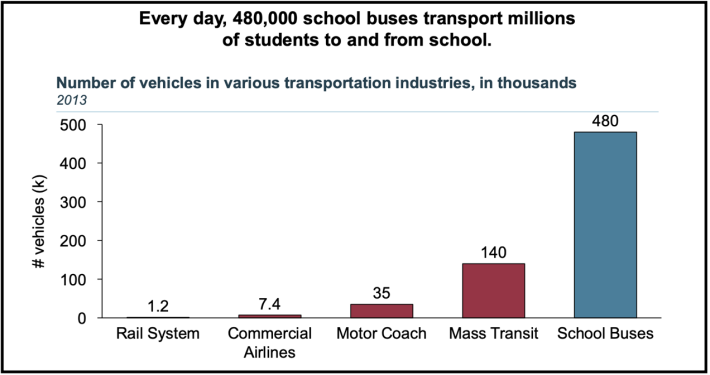

Labor advocates aren't the only ones who should be concerned. Buses are one of America's single largest forms of mass transit, despite a relative lack of support from public transportation advocates. School buses outnumber other forms of public transportation vehicles almost 3.5 to 1, and they're ridden by about a third of school-aged kids, who take a collective total of about 52 million trips a day. Other forms of mass transportation, by contrast, have 34 million daily boardings, and transport just 10 percent of American commuters each day — and that's including children who ride the city bus to class rather than the yellow bus.

The reasons why school buses have escaped advocate attention are complex. Unlike like other forms of mass transit, school buses aren't always purchased with public dollars, nor are their drivers directly paid with taxpayer funds. Today, only about 60 percent of school vehicles are owned by schools themselves, in large part because of federal and state cuts to education funding. The other 40 percent of buses are run by private contractors — almost of all of which were ignored in the last round of federal COVID-19 relief, the CARES Act. These companies have never recovered from the blow.

And that was before the research community discovered what it will really take to make shared transportation safe — or how much money it would require on the part of operators.

In its new guidelines for school re-opening, the Centers for Disease Control urged operators to limit students on the bus to as few as one child per every two rows, require masks for children and drivers, and provide comprehensive cleaning between rides — all of which would require more money, staffing and even vehicles. The ATU notes that its members would like to see even more safety measures than the CDC's minimum, including plastic partitions for drivers, UV-light cleaning systems on buses, and vehicles capable of rear-door boarding.

Meanwhile, President Trump tweeted on Wednesday that he would urge the CDC to soften its guidelines, saying they were "very tough & expensive," as well as "very impractical." (CDC Director Robert Redfield has already said the agency would not back down, but noted it would "provide additional information to help schools be able to use the guidance we put forward.")

In districts like New York City, which are planning to stagger students' schedules, bus operators will face even more challenges. Under such a program, students may attend schools only on two or three days, or depart and arrive at staggered times — leaving drivers either underemployed or overworked, depending on the day. Districts will almost certainly need to spend more on buses, drivers, and network planners as the pandemic and the policies crafted to respond to it continue to throw transportation patterns into chaos. The arc of the pandemic also complicate matters even further, especially if parents suddenly pulled kids off of buses in response to COVID-19 spikes.

But unless public schools shut down again — a move that would be a disaster for millions of families, especially low-income families of color — the need for school buses will never disappear.

"Not every parent has a car. Not everybody can even afford a car," said John Costa, ATU's International President. "And not every parent can drive their kids to school. They're relying on the school district to get their kids to class, and they're paying taxes for that service."

And even if all parents somehow could drive their kids to school, failing to save the American school bus would be a safety disaster — because kids are much safer on buses. Car crashes are a leading cause of death among children under 18; 675 children died of traffic violence in 2017, the last year for which data is available. Yet an average of only six children each year are killed in school-bus crashes, with another 19 killed in pedestrian crashes related to entering or exiting buses. Experts worry that taking kids out of buses and putting more cars on the road will kill more children.

"The school-bus industry is one of the safest modes around. They're built like tanks," said Rosenberg. "The operators are very hard-working and dedicated people who make sure that kids are safe from the time they get on the bus to the time they get off. But they can't do it unless the companies have the money to help them do it."