It's not every day that safe streets advocates have a reason to celebrate drivers going faster, but here's a rare one: with private vehicles largely purged from American highways by COVID-19-curbing travel restrictions, truck delivery of essential goods is reaching cities quicker than ever.

Freight trucks along Atlanta's infamous "Spaghetti Junction" intersection are moving 258 percent faster than normal. Ditto New York City's notoriously congested I-495, where freight speeds have more than doubled, too.

Even in Los Angeles, which is also experiencing a reported surge in freight demand by homebound Angelenos, the trucks are zipping along. Truckers who try the thorny intersection of I-170 and I-105 during peak morning travel hours hit average speeds of 53 miles per hour last week — a velocity that's just a few miles short of the post speed limit. On a normal day before this whole crisis began, trucks averaged under 25 mph — frustrating for a trucker, and damaging to the national economy.

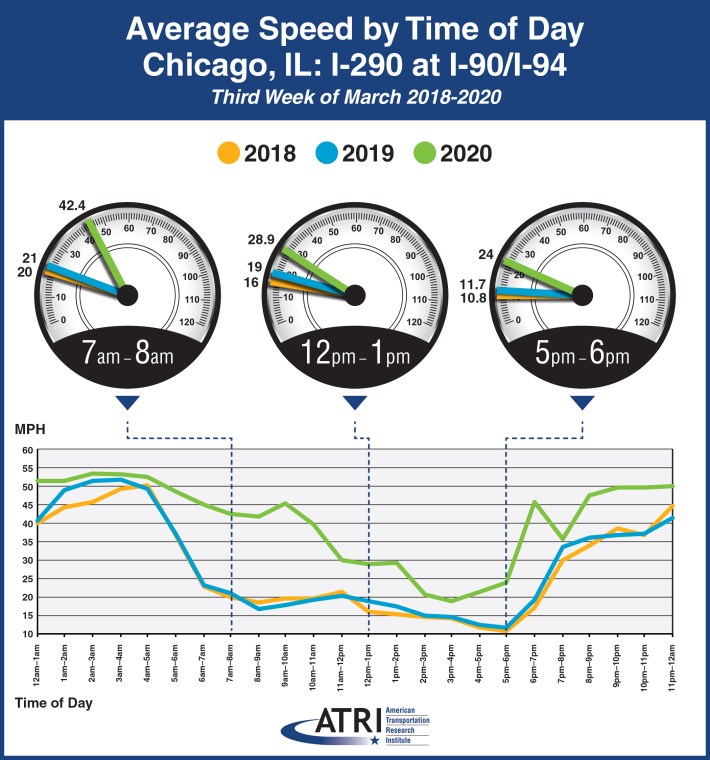

"We were definitely surprised," said Rebecca Brewster, president of the American Transportation Research Institute, which reported the latest data. "We knew trucks were moving faster, but we just had no idea just how significant those changes would be. It really points to how much we can do as a freight community when there are fewer cars on the road."

Though it's an under-discussed topic in the bicycle and pedestrian advocacy world, freight trucking is a bedrock of our current national supply chain. Even some #BanCars advocates acknowledge that the world would probably be better off if our highways were the domain of more fast-moving freight trucks rather than a slow-moving mix of trucks and cars — at least until we build a greener option, like a comprehensive national freight rail network.

But until that happens, road freight will be a big part of our lives. As much as 70 percent of our nation's goods are currently delivered by trucks rather than trains, planes, or boats, and slow-downs can cost the planet dearly in the form of idling emissions. And that's in non-pandemic times, when trucks are doubly essential to deliver the Lysol wipes and dried beans that panic-buying households across the country need — not to mention the medical supplies our hospitals are still struggling to get their hands on.

But even if we agree that improving truck delivery times is important, the things we've historically done to accomplish it have mirrored the worst parts of car culture. Freight efficiency is a frequent justification for highway expansion projects — even though we've known for years that adding lanes just makes congestion worse. COVID-19 has inadvertently revealed a method that does keep trucks moving: implementing policies that reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMT) by other private drivers, so commercial drivers can have the rule of the road.

Of course, the policies subtracting cars from American streets right now weren't intended to curb VMT — they're blanket travel restrictions intended to curb the spread of COVID-19. But there are countless less painful ways that we can reduce private driving on highways even after COVID-19 subsides, from good-old-fashioned tolls, to expanded work from home policies, and even cash benefits for non-drivers.

And it should be noted, of course, that when it comes time for trucks to exit the highway and venture into our cities, high truck speeds are a disaster — because fast-moving freight is deadly for walkers. That's why many safe streets advocates have long argued for a safer urban delivery model that requires large trucks to stop at distribution centers outside the city, to split their loads among smaller vehicles. (And yes: those "smaller vehicles" should include bike couriers.)

But until we have a true revolution in freight delivery, we can at least celebrate the fact that there are fewer private cars on the highway — and that trucks are getting respirators to hospitals a little faster because of it. And while Rebecca Brewster isn't sure that the trucking industry is likely to become an ally of the VMT-reduction movement anytime soon, she says the industry is enjoying the plunge in traffic while it lasts.

"Is it realistic that we’ll continue to see this kind of operational efficiency once COVID-19 is over and people get back on the road?" she says. "No, probably not. But are we thrilled that trucks are moving this fast now? Yes."