Demand “Safe Streets for Everyone” at the National Bike Summit, hosted by the League of American Bicyclists March 15-17. Meet advocates from across the U.S. who are reshaping their communities and make your voice heard on Capitol Hill. Explore the Summit here.

Rideshare companies such as Uber and Lyft have been promising to end private vehicle ownership, make our streets safer, and cut car emissions since they rolled onto city streets almost 10 years ago — but a groundbreaking new study says the last of those promises has been broken.

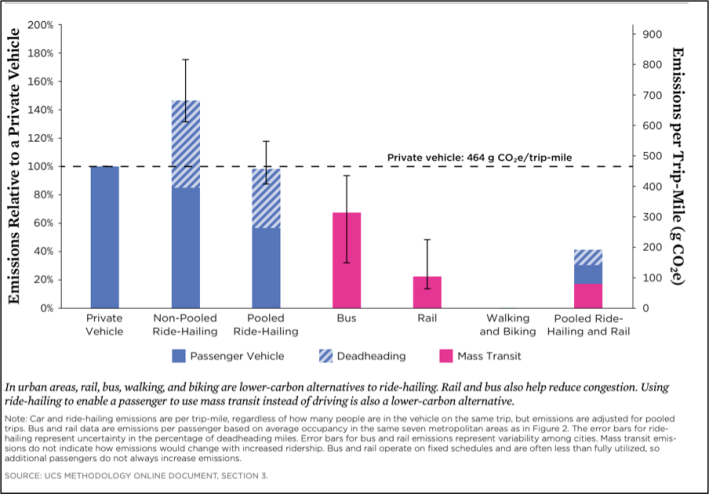

News broke last week that the average ride-hailing trip is responsible for 69 percent more carbon emissions than the trip it displaces, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists. That's in large part because the people who opt for a digital dial-a-ride are actually ditching a far greener transit, bike, or walking trip 24 percent of the time.

Driver "dead-heading," or the time spent circling the city waiting for a rider, is the other big reason why rideshare trips cause so many emissions — because the drivers of private cars park and turn off their engines more often while they go about their business than the average Uber driver does.

The study might seem obvious to sustainable transportation advocates — but it's a bombshell to average Americans who bought the hype of trip-hailing apps. As recently as two years ago, even the Union of Concerned Scientists was wondering whether ride share might be a boon to the climate, especially if the industry could increase the share of carpooling, provide links to public transit, and encourage electric vehicle adoption.

But, a decade into our national experiment, it's becoming clear that ride-share giants didn't do those things — and that they've hurt our cities.

Broken promise #1: Rideshare will reduce private car ownership

Lyft's president John Zimmer famously proclaimed that private car ownership would end in cities by 2025 — and that his company would help it happen. It's been four years since he made his prediction, and per capita car ownership has actually grown in the cities where ride share is most heavily used.

Bloomberg's Joshua Brustein recently reported that Lyft and its ilk haven't put a dent car in ownership because Americans see ride-share mostly as an occasional alternative to their everyday private vehicle. Drivers tend to call an Uber to avoid driving home rom a boozy dinner, or if they don't want to fight to find parking in a busy downtown area — but when it comes to their daily commute, they don't give up their cars.

As for people who don't have a car, ride-share is often responsible for putting them in one. "[Mobility companies] attract people who weren’t driving anyway," Brustein said. "When Uber and Lyft riders are asked in surveys how they would have completed a particular trip had ride-hailing not been available, they’re most likely to say they would have taken public transportation, walked, or stayed home."

Rideshare companies won't end private vehicle ownership for another simple reason: Almost every car in their fleet is a privately owned car, being driven by a gig-economy worker who the company is relying upon to keep making those car payments. As Uber expands into the largely untapped autonomous-car space, the company is still not investing in vehicles, and experts speculate that it couldn't afford to even if it wanted to. So much for a mobility revolution.

Broken promise #2: Rideshare will increase carpooling

Carpooling doesn't get a lot of press as a common-sense step to making transportation more sustainable in American cities, though advocates have been arguing for years that it should. That might explain why, as late as 2017, MIT researchers were breathlessly praising ride-share's trip-pooling potential as the hot new invention.

Using advanced computer modeling, the Cambridge researchers concluded that "carpooling options from companies like Uber and Lyft could reduce the number of vehicles on the road by a factor of three without significantly impacting travel time." It's the kind of thing that sounds plausible enough — after all, an app that puts you in the back of a taxi with a stranger you've never met instead of putting the onus on riders to hitch a ride with a stranger sounds pretty exciting.

But when researchers looked past the computer models and start studying street-level data, it wasn't so simple. As of 2018, studies showed that just 20 percent of Uber riders chose to share a backseat with a stranger over the convenience of solo trips. Lyft did a little better with their Shared Ride program — 35 percent of users took advantage of cheaper pricing on the pool option — but that's still a long way from American commuters putting aside their collective fears of being trapped in close quarters with smelly weirdo they've never met and piling in the back of some guy's van.

Broken promise #3: Rideshare will bolster transit

Remember when everyone thought that we'd all take Waze rides to the metro stop, and transit ridership would skyrocket? Yeah, we're not doing that.

The rise of rideshare was actually responsible for a 12.7 percent drop in transit use nationwide in its first eight years, according to one study.

Nonetheless, desperate public transportation agencies are clamoring to lure users who don't live near lines by subsidizing Lyft rides that end at train and bus stops. But many of them are finding that embracing rideshare is an expensive substitute for simply expanding the transit network. Metro officials in Toronto realized their Uber-to-Transit program's "success" was costing their city more money than the increased fares the program took in. An unscalable solution doesn't last long — so don't count on rideshare to integrate meaningfully into transit networks anytime soon.

Broken promise #4: Rideshare will help cure congestion

It's hard to understand why anyone thought taxi companies that encourage their drivers to circle the roads in order to reduce wait times for passengers would reduce traffic congestion.

But that's exactly what researchers at the University of Santa Barbara argued in 2016, on the strength of another abstract computer model. There are a few reasons why the model was wrong, but here's one big one: researchers assumed that human beings are rational people who will pay less money for a shared ride, rather than jerks who assume strangers are icky and will hand over cash to avoid them. Still, the media trumpeted the study — until the evidence that it was wrong became overwhelming.

In the fall, Uber and Lyft finally admitted that their fleets are crowding city streets — but pointed out that, because most cars don't have a gig worker in the driver's seat, private drivers are still responsible for way more traffic than rideshare. It was an audacious argument coming from a company that was named among biggest contributors to congestion in San Francisco, New York, Boston and more. When you factor in that ride-share is stealing passengers from transit, it's even worse.

Broken promise #5: Rideshare will save non-driver lives

Rideshare companies have never made many promises about their potential to make streets safer for non-drivers — probably because most Americans just accept an epidemic of non-driver deaths as the price we pay to get around. But still, the idea that Uber and Lyft drivers have a "market incentive" to drive carefully has become a frequent mantra among ride-share proponents.

The problem? Even the most careful ride-share driver is still driving a car — and more cars means more dead pedestrians.

As many as 1,100 traffic deaths per year are directly traceable to Uber, Lyft and the like, according to a 2018 study. That's enough to nudge our national traffic-death totals up two to three percent over that period.

If we want to save lives, the planet, our transit system and our sanity, we should recognize U.S. rideshare companies for what they are: just another way to super-charge car culture. Then we should talk seriously about how we can break that culture — and it won't be as simple as swiping for a ride.