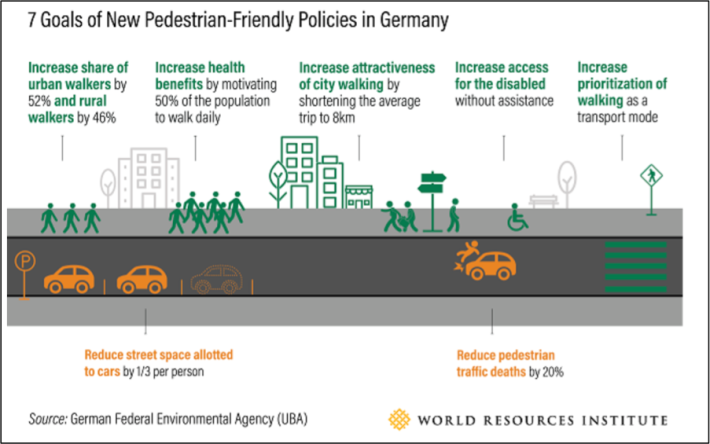

Germany doesn’t have a single goal to improve the pedestrian experience on its streets — it has seven.

That’s right: Germany not only has a comprehensive National Walking Plan — something American street-safety advocates only dream of — but its transportation leaders are holding themselves accountable to seven distinct benchmarks for measuring how their policies affect the safety and comfort of people on foot.

Seriously, just check out this infographic, which spells out exactly how walkable Germans want their cities to become by 2030:

It’s a shocking contrast to the American approach to pedestrian policy and goal setting. The Federal Highway Administration doesn't even have national pedestrian-fatality-reduction goals; its last safety plan focuses, instead, on such non-quantifiable targets as "Motivate drivers to look for and stop for pedestrians" and the maddening "motivate pedestrians to use crosswalks and designated-crossing locations."

That's perfectly in keeping with America's broader approach to roadway safety. Last week, U.S. delegates only reluctantly agreed to an international pledge to reduce total roadway fatalities by 50 percent in 10 years, giving the excuse that “not all” nations had agreed to the target before the pledge was drafted. (Read: They didn't think halving road deaths was realistic, even as city after city eliminates them.)

Germany signed the 50 percent pledge, which makes its pedestrian-only safety goals even more impressive. Deutschlanders are pledging to reduce non-driver/cyclist fatalities by at least 20 percent by 2030; they're also requiring states to set aggressive cycling-fatality-reduction targets as part of a National Cycling Plan.

But the push doesn't just stop at safety. The Germans also aim to make walking more attractive and convenient by shortening the average pedestrian trip to under 5 miles, increasing accessibility for disabled people, and reducing car use.

That’s a night-and-day difference from U.S. pedestrian policies, which focus almost exclusively on increasing safety through modest gains in pedestrian infrastructure — and don't address the question of whether walking is comfortable and attractive.

But as a decade of rising American pedestrian-fatality stats has shown, adding meager amounts of pedestrian infrastructure to otherwise completely car-focused streetscapes in hopes of saving lives doesn’t even work. “This supply-side oriented approach has not delivered the expected benefits [in the realm of pedestrian safety,]” German consultancy group GIZ said in a report about its country's pedestrian policy. “Induced traffic has been created and roads continue to exhibit unacceptable levels of congestion, greenhouse-gas emissions and other externalities. For this reason, the traditional approach is nowadays regarded as obsolete.”

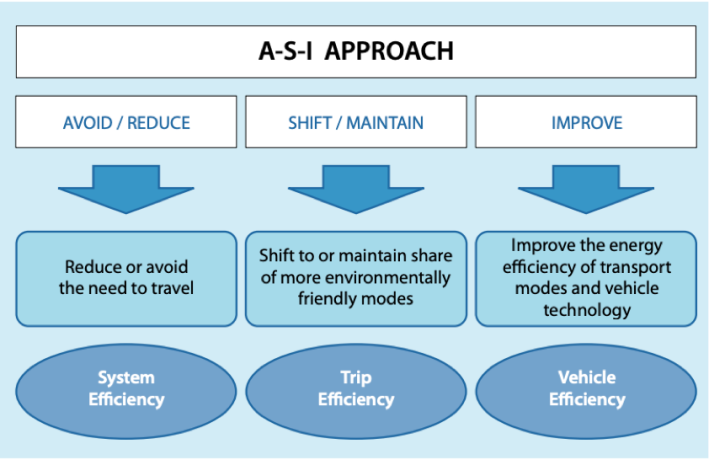

That’s a very German way of saying that the traditional — read: American — style of cars-first, pedestrians-later transportation planning totally sucks. There’s a better way, and it’s called the Avoid, Shift, Improve model, or ASI.

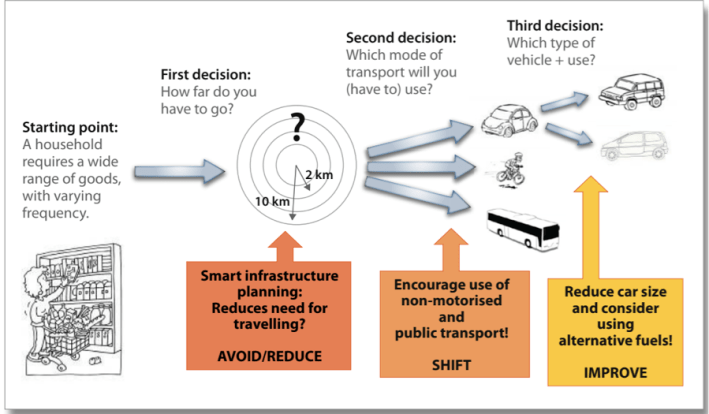

Rather than simply focusing on pedestrian-friendly infrastructure, an ASI approach demands that cities, states and even nations think more holistically about saving lives on their streets. The “avoid” column — which refers to policies designed to reduce the necessity of long trips usually taken by car — is especially under-discussed in American transportation policy, because, of course, it falls outside the realm of traditional transportation planning. The ASI model insists, however, that leaders think broadly about housing, commercial development, and creating complete neighborhoods in which people don’t need to drive to the grocery store or their kids’ school, because essential services are right next door.

Here’s another look at the ASI approach that even more concisely illustrates why Americans need to stop treating pedestrian safety as just an infrastructure problem, and start thinking bigger.

It’s refreshing to see a transportation plan that doesn’t start with cars, and instead positions private motor vehicles exactly where they should be in our road hierarchy: as the mode of last resort. If America wants to do better by its pedestrians, we should open up our minds, set many ambitious goals to make sustainable transportation better, and — just maybe — start thinking like the Germans.