Americans are taking on more debt than ever at the car dealership — and the rise in risky auto lending has everything to do with our national rise in pedestrian fatalities.

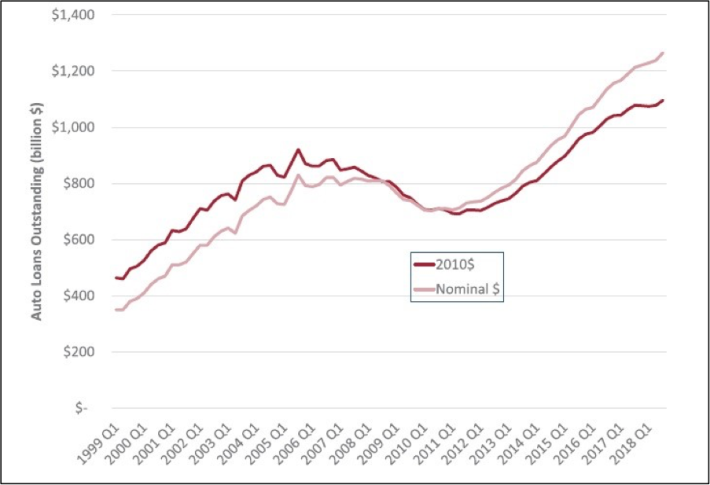

The total amount that Americans owe on their cars rose a shocking 75 percent from 2009 to today, according to a new report from the Frontier Group. But the trouble isn’t just that more people are buying cars they can’t afford. It’s that lax lending policies are allowing them to pick huge, expensive cars — and, as Streetsblog has documented, the bigger the car, the more lethal it is to pedestrians.

SUVs and light trucks have become the vehicle of choice for U.S. drivers over the last decade, grabbing a record 70 percent of the market in 2019. That’s a stark contrast from 2009, when Americans tightened their belts in the wake of the financial crisis and opted for cheaper rides. Smaller cars outsold assault vehicles just 10 years ago — but as the economy recovered, so did buyers' appetites for big cars.

And as cars got bigger, more pedestrians started dying. Many media outlets have connected the 10-year explosion in pedestrian fatalities to the growing number of SUVs on our streets, largely because more massive cars strike walkers at the head and neck rather than at the chest or the knees, which is less fatal.

We can stop this trend — and reforming the car-loan industry could be a crucial step. But how did we get here?

Easy money for killer cars

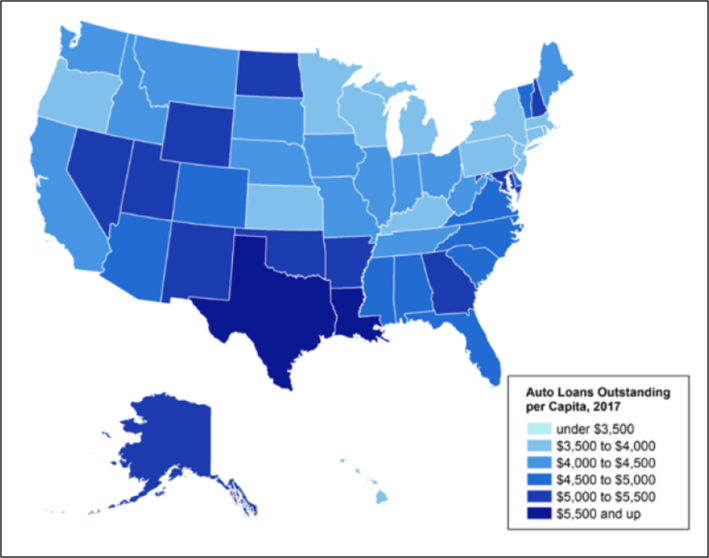

A raft of factors contributed to the rise of the mega-car on American roads: Low gas prices, consumer perceptions that big vehicles are safer, and a strong jobs market all played a role. But though the influence of loosening auto-lending standards on SUV purchases is less well-documented, it shouldn’t surprise us that, when you give consumers in an SUV-obsessed culture easy access to large auto loans, many will pick the biggest car they can get their hands on.

And when we say “easy access,” we really do mean easy. In the wake of the financial crash, the auto-loan industry not only expanded access to high-interest “subprime” loans for borrowers with low credit scores — a predatory tactic that leaves low-income vehicle owners vulnerable to default. It also extended the life of the average loan — 42 percent of auto loans issued in 2017 carried a term of six years or longer, compared to just 26 percent in 2009.

“It changes a person’s calculus of what car they should buy,” said Frontier Group policy analyst R.J. Cross. “In the era of Netflix and endless monthly subscription services, people are starting to determine how much they can afford not by the sticker price, but in terms of what they’ll actually pay per month. Cars are no different.”

A "low" monthly payment is a powerful incentive to pick a spendy SUV over a sensible sedan — and it opens up a new market of buyers who otherwise might have chosen a smaller, cheaper car that would be less lethal to a pedestrian in a crash.

The rise in “roll over” financing has been a boon to SUV dealers, too. Increasingly, car dealerships allow buyers who trade in old vehicles with outstanding loans to add their unpaid balance to their new car payment. The practice allows drivers to upgrade to bigger cars they can’t really afford even before their current ride is paid off — and puts them at huge financial risk if they can’t make the new-car payment.

Ballooning car loans leave drivers stranded

But whether or not they realize it, drivers who take on big loans for big cars are getting a raw deal.

The average American household already spends about 13 percent of its income on transportation — a proportion that will only rise as Americans get more access to loans at the dealership. It’s not hard to imagine what will happen to a nation full of debt-saddled drivers in the event of an economic downturn: mass repossession.

“In the wake of the financial crisis, we think people reasoned that, well, if worst came to worst and I lost my house again, I’d still have a car, and at least I’d be able to get to work,” Cross says. “But what if you took on so much car debt that you can’t afford the payment anymore? What if you lost your car, too?”

If our collective car-loan burden is bad news for individual families, it could be even worse news for the national economy. While the ballooning auto-loan industry isn’t exactly a “bubble” in the way that the 2008 mortgage industry was — the average new car only holds about 35 percent of its value five years after its driven off the lot, which means that almost all auto borrowers are technically “underwater” on their loans — a car-repossession crisis would still be devastating in auto-dependent communities. And because almost all American cities are auto-dependent, that'd be a disaster for the entire GDP. In most American cities, even the poorest workers rely on their cars to commute to their place of business — or drive to the store and support anyone else's.

But even if such a crisis never happens, the auto-lending balloon is still a national concern for one reason: because it’s helped unleash a growing number of pedestrian-killing SUVs and trucks on American streets. We need to use every weapon in our arsenal if we want to reverse our horrifying traffic-violence trends; perhaps reforming the auto-loan industry should be the one we reach for next.