One of the hallmarks of federal transportation funding during the Obama administration was a new willingness to support streetcar projects. With the first wave of these projects now in service, their shortcomings are becoming more apparent.

A report published earlier this year in the Journal of Transport Geography sheds light on the limits of these streetcars: They were always intended mainly to spur real estate investment, not to address urban mobility needs. As authors David King and Lauren Fischer explain, streetcar backers were often more concerned about land development than the transportation system.

The new streetcar segments typically run a short distance -- a few miles at most -- in mixed traffic, and they aren't well-integrated into existing transit networks. So it should come as no surprise that ridership is often underwhelming.

On Detroit's QLINE streetcar, for example, ridership dropped 40 percent after M-1 Rail, the company that operates the 3.3-mile route, started charging a $1 fare last month. Passengers now take about 3,000 QLINE trips each day. A spokesperson for M-1 Rail told NextCity he "fully expected ridership to dip a little bit" once the fare took effect.

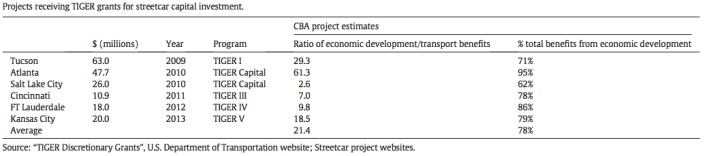

The primary benefits of streetcar projects were always intended to be related to development. King examined the official cost-benefit analyses that streetcar sponsors submitted to the Federal Transit Administration. About three-quarters of estimated benefits derived from economic development, not transportation-related improvements, he found.

King identified 12 new streetcars in operation and a few dozen more in various stages of development. All told, local and federal government spent $866 million on streetcars between 2009 and 2013, he reports, with 32 percent coming from the White House's TIGER grants. Several of the projects were subsidized with local tax incentives or special sales taxes.

The new wave of streetcars have a regressive effect, King writes, because the costs are widely distributed while the benefits are concentrated in the form of higher land values. Ironically, he says, that helped boost political support for streetcar projects, many of which are backed by business associations and downtown property owners.

Cities may have valid reasons for seeking more downtown investment, but these streetcars should be recognized for what they are: economic development projects, not solutions to the transit and transportation problems cities face today.