Young adults today drive less than previous generations did at the same age -- that much is clear. The question is why.

The cause of the shift is a subject of dispute. Graduated driver's licenses, changing attitudes among young people, economic contraction, and the rise of mobile communications have all been floated as explanations.

A pair of new studies by researchers at UCLA seeks to provide some answers [PDF, PDF]. Here's what they found.

Rising youth unemployment is a big factor

Using data from the 2001 and 2009 National Household Travel Survey, Evelyn Blumenberg and her colleagues at UCLA found that people age 15 to 26 drove about 18 percent fewer miles than previous age cohorts at the same stage of life. But the researchers concluded that this shift was primarily a reflection of rising unemployment.

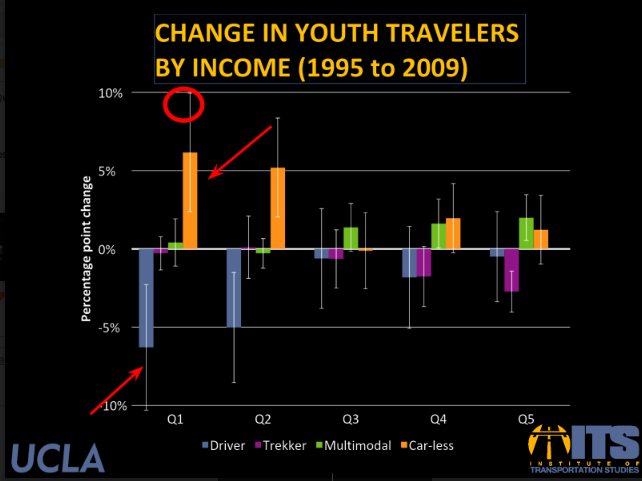

The employment rate for this age group fell from 70 percent in 2001 to 56 percent in 2009. During this time the share of carless young people rose from about 9 percent to about 15 percent. The increase in carlessness was concentrated among young people in the bottom 40 percent of the income scale.

While there was some degree of mode shift to transit and biking independent of changes in employment, the research team says this effect was much smaller than the decline in driving due to economic factors. "We see a situation where people are really not traveling much by other means, they're really not traveling as much at all," co-author Brian Taylor explained in a webinar hosted by the Eno Center for Transportation.

For many young people, transit isn't really an option

While there is evidence that young people prefer urban environments, the fact remains that there aren't that many walkable urban places in the U.S.

Only about 4 percent of U.S. neighborhoods are considered "old urban" -- dense, walkable, with good transit options. Half of those neighborhoods are in the New York City region, and 90 percent are in the nation's five largest metro areas.

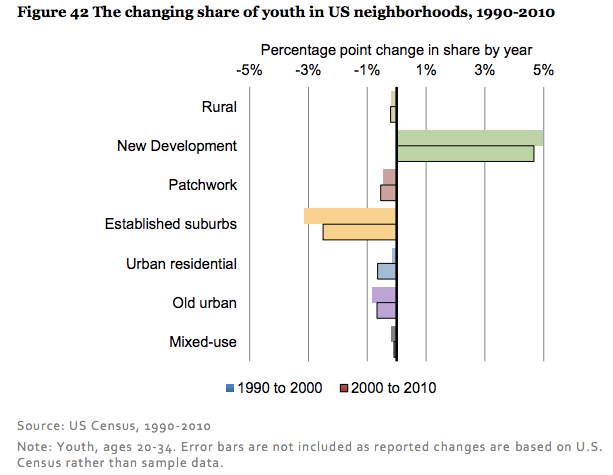

So the parts of the country that are capturing a bigger share of the population between age 20 and 36 remain sprawling new suburban development (see top chart).

As Taylor put it in his presentation, "The places where we're seeing the most driving still are the places that are growing the fastest, even with some of the urban revitalization that we're seeing around the country."

A big shift in travel behavior won't happen without big shifts in policy

Barring major changes in transportation policy or land use patterns, significant declines in driving are not likely to be sustained.

"We cannot see any evidence in our work that some demographic deus ex machina will come in and save the day," said Taylor.

Changing travel behavior still boils down to good old policy reform -- restructuring incentives to favor modes of travel other than solo driving, creating better access to transit and safe walking and biking, and allowing more housing and development in urban places.