In a new report, Highway Boondoggles 2 (the original came out in 2014), U.S. PIRG and the Frontier Group teamed up to profile the most wasteful highway projects that state DOTs are building. Streetsblog will be serializing the case studies in the report. Yesterday, we looked at Connecticut's $11.5 billion I-95 widening. Today, we focus on a proposed $3.3 billion highway widening in Tampa.

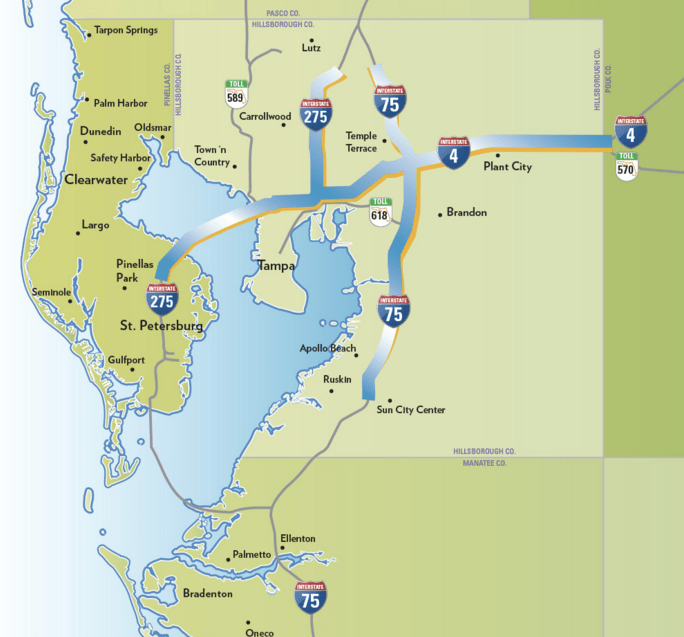

The Florida Department of Transportation acknowledges that a decades-old plan to construct toll lanes allowing paying drivers to bypass congested traffic on I-275, I-75 and I-4 in Tampa would not solve the region’s problems with congestion, but is pushing the project forward anyway in the face of community opposition.

Starting in the late 1950s, the Florida Department of Transportation built I-275 through the middle of Tampa, “ripping holes through neighborhoods such as the historic Central Avenue business district, Seminole Heights and West Tampa,” as a local newspaper columnist put it.

In 1996, plans to expand that stretch of I-275 were approved by the Federal Highway Administration. That project was never built. For years the plans laid dormant. In the meantime, the neighborhoods began to rebuild themselves.

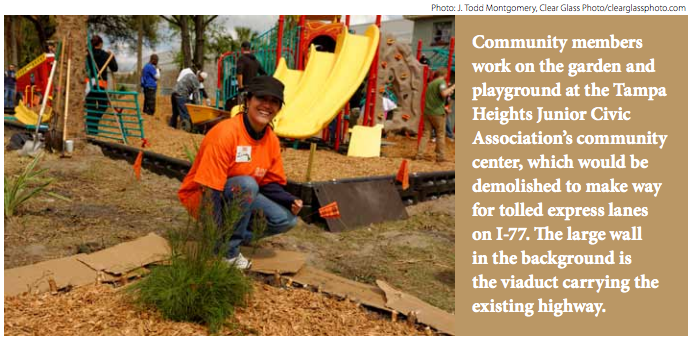

Under an agreement with the state, community institutions used land owned by the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) to expand their presence (on the condition that any structures would be demolished were the highway ever to go through). The Tampa Heights Junior Civic Association, for example, raised and spent $1 million to convert the former Faith Temple Baptist Church on the property into a community center that now offers pre-college and pre-professional classes for local teens.

Outside the center are a community garden, a playground and a walking and biking trail. Improvements in the building, both planned and already under way, were stopped by a November 2015 cease-and-desist order from FDOT, indicating the highway project is moving forward.

The projects were to build a teaching kitchen, an aquaponic garden and a sound studio, all for teaching young people new professional skills. Community leaders are concerned the order might mean the dismantling of some of the work already completed, and even require the refunding of donations.

In mid-December 2015, FDOT and the city of Tampa rejected a request from the community group to be allowed to continue improving the building. The highway expansion would also destroy historic homes and businesses, centers of culture and community life, and even part of a popular water park the city spent millions to build and open in 2014.

For nearly two decades, local officials thought the highway expansion would never come. “I sat on Tampa City Council and the Metropolitan Planning Organization [in 1996], but never believed that [the expanded highway] would be built because it was such a dreadful plan and so expensive. Surely we would embrace transit and quit widening the interstate and destroying neighborhoods,” wrote Linda Saul-Sena in a local newspaper in June 2015.

The community expressed its preferences in 2014, with Plan Hillsborough, the county’s transportation planning agency, approving a long-range transportation plan focusing significantly on transit improvements, and specifically aiming to decrease fossil fuel consumption and dependence on single-occupancy vehicles. Both would be increased by construction of the proposed highway lanes.

The long-range plan highlighted the facts that nearly half of Hillsborough County residents don’t have access to transit routes, and more than one-third of county residents are unable to transport themselves or purchase transportation. The plan detailed significant community-wide benefits for those investments, including boosting economic development, energy conservation, environmental quality and local quality of life.

Nevertheless, the dormant 1996 highway expansion plan came back to life in May 2015, under a slightly different guise. While beginning another major highway project in the area, the I-4 “Ultimate” expansion, FDOT decided to include the tolled express lanes along I-275, even though they were not included in the state’s upcoming highway project list, which extended out to 2040.

The DOT projects that the new highways would bring between 5 and 24 percent more traffic than would use the roads if the project were not built, making the highways likely to produce more pollution and noise than they currently do. Those threats to their community – and the potential for demolition of 100 homes and 30 businesses – brought out local residents in opposition.

In June 2015, after hearing from dozens of affected community members, the Tampa City Council voted to oppose the project, unanimously agreeing to lobby state legislators, local planning officials and other state leaders. The council also asked city attorneys to consider filing a federal complaint alleging the project would discriminate against the local residents.

Councilman Mike Suarez, a third-generation Tampa resident, denounced the highway project to a local newspaper as “not good for the neighborhood; it’s not good for the city.” In August 2015, Plan Hillsborough, the same agency that just a year before had approved the transit-promoting long-range plan, voted to include the express lanes in its five-year transportation plan.

But conditions on that approval include requirements to reduce the project’s effects on urban neighborhoods, and to reevaluate the 1996 plan. The region’s top transportation official, FDOT District 7 head Paul Steinman, told the Tampa Tribune that the new lanes on their own won’t solve the region’s congestion problem. He said transit will also be needed to address the problems Tampa residents and commuters have getting around.

So far, all FDOT has offered is $1 million to study an expansion of a city streetcar line. A significant opportunity for the state and local government to invest in a transportation project that would further the community’s goals presented itself in late 2015. Rail giant CSX is interested in selling 96 miles of existing rail tracks that connect downtowns in Clearwater, St. Petersburg and Tampa, as well as the key destinations of Tampa International Airport and the University of South Florida.

The tracks are currently used -- infrequently -- for freight but could be the basis for a revitalized push for commuter rail, which the region currently lacks. The cost is not yet determined, but a similar project in Orlando allows some comparisons. In 2011, CSX sold 61.5 miles of tracks for $2.4 million a mile, on which Orlando started a commuter rail line. The total cost for that project was $432 million, half paid with federal dollars and the rest with state, city and county funds.

Assuming a similar track-mileage-to-cost ratio, the Tampa track purchase could cost $234 million, with another $440 million in additional costs, such as rail cars and station construction.