It's more than a little ironic that in many places, hospitals are some of the worst offenders when it comes to perpetrating unhealthy transportation patterns. Often surrounded by enormous parking decks, hospitals have earned a reputation as isolated institutions hermetically sealed off from surrounding neighborhoods.

But that's beginning to change. Healthcare providers are undergoing a fundamental shift from focusing on contagious diseases to treating chronic conditions that are often related to unhealthy lifestyles, like diabetes and heart disease. Industry leaders like Kaiser Permanente are pushing reforms not only in healthcare policies and procedures, but in the physical form of hospitals and the role they plan in their communities, write Robin Guenther and Gail Vittori in their book, Sustainable Healthcare Architecture.

I asked Guenther which hospitals are leading the shift to healthier transportation practices, and she singled out Seattle Children's Hospital as the best model by a wide margin. It is indeed impressive.

In 2008, under pressure from the city of Seattle, the hospital mapped out a comprehensive transportation plan [PDF] calling for major reductions in solo car commuting. Even before that, the hospital had demonstrated leadership. Beginning in 2004, it used a combination of strategies to reduce the share of daytime commuters who drive alone to work from 50 percent to 38.5 percent.

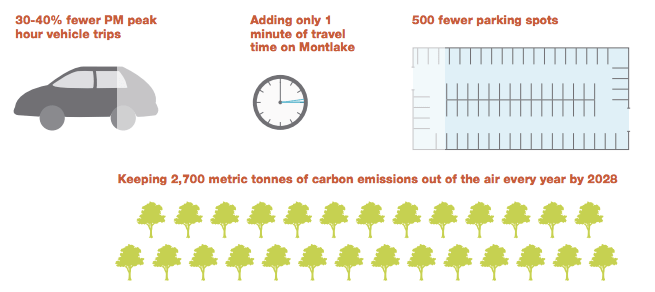

The 2008 plan laid out a new target: to reduce the share of commuters who arrive alone by private car to 30 percent by 2028. As part of an agreement with Seattle City Hall, the hospital's permitting to build new clinical space is tied to reductions in solo car commuting.

"The reduction of [single occupancy vehicle commuting] in our case is tightly tied to our ability to grow our business," said Jamie Cheney, the hospital's manager of transportation systems. "We have commitment at the highest level of Children’s."

So the hospital has rolled out a multi-faceted strategy to cut down on driving, running more than a dozen programs to reach its goal.

"One way we think about reducing [single occupancy vehicle] commuting at Seattle Children’s is to think about tipping the scales," said Cheney. "We make it more attractive to take alternatives and less attractive to drive."

For starters, the hospital offers free transit passes to all employees. In addition, employees who pledge to bike to work two or more days a week are given free bikes. Those who don't drive also get a bonus in their paychecks: $4 a day.

Parking policy also plays a huge role in the hospital's efforts to reduce driving.

"Whether you’re a physician or an administrator or clinician, everybody pays to park," says Cheney.

The rates are variable, depending on when workers arrive and how long they stay, ranging from $2.25 to $10 a day. Charges are highest for employees who arrive during prime commuting hours.

Another key aspect is the way parking payments are structured, says Cheney. The hospital charges drivers daily, rather than by week or month, to apply the strongest possible incentive.

"There are no monthly parking passes," she said. "You pay by the day. That monthly pass is really a 30-day investment. It sends a signal to somebody to optimize that investment by getting as much parking as possible by driving."

The hospital also requires some employees to park in an off-site lot and take a shuttle to the hospital.

Seattle Children's Hosptial also offers one of the largest vanpool programs in the Seattle region. The program is administered by King County Metro, but the hospital provides discounted rates to its employees. Vanpool vehicles also receive free parking at the hospital. About 35 vans serve the hospital, and about 19 percent of the hospital's 6,000 employees rely on a vanpool or carpool to get to work, said Cheney.

The hospital sweetens the deal by providing people who opt for a shared vehicle a "free ride home" from a taxi service in the event that an emergency with one driver leaves the other one stranded.

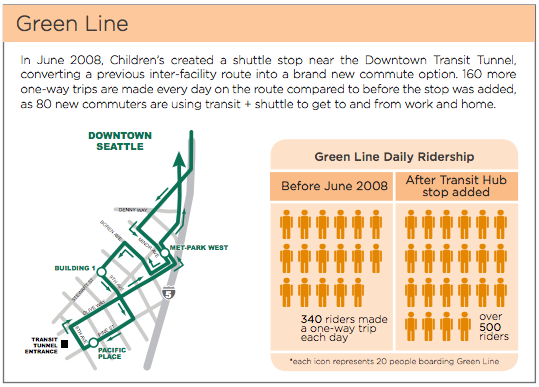

That's crucial, because Seattle Children's Hospital is located in a residential neighborhood that isn't well-served by buses or trains, said Cheney. Even so, about 19 percent of employees opt for transit. One way the hospital assists is by shuttling commuters from nearby transit hubs to the hospital.

To make the campus itself more walkable, the hospital made a a special effort to attract useful business and services for employees, like restaurants and daycare centers, to the neighborhood.

In part because of the hospital's limited transit access, biking is a big part of its strategy. About 25 percent of employees live within three miles of the hospital, making for an ideal bike commute. In addition to the free bike program for bike commuters, the hospital recently opened its own, on-site bike shop, offering employees free maintenance and discounts on bike gear.

Among hospital employees, about 9 percent now bike to work, nearly double the citywide average, says Cheney. Lisa Brandenburg, the hospital's president, is a bike commuter herself. The hospital hopes to increase its bike commute mode-share to 10 percent.

If the hospital reaches its ultimate goal of a 30 percent car commuting rate by 2028, it will avoid constructing 500 parking spaces. That will save 225,000 square feet, enough to support 56 patient beds. At a construction cost of $40,000 per structured parking space, it will save the hospital an estimated $20 million.

While the hospital's driving reduction programs do cost money to administer, much of that is offset by revenues from parking fees, said Cheney. And the programs are viewed as perks that help retain and attract employees, she said.

"Our employees really appreciate that we subsidize transit and bicycling and walking and carpooling," she said. "It’s essentially seen as a benefit. It’s helpful in our attraction."

While Seattle Children's Hospital is already more than halfway to its goal of getting from 50 percent car commuting to 30 percent, Cheney says the hardest part is yet to come.

"The low-hanging fruit is kind of gone," she said. "It was fairly easy to move certain people out of their vehicles."

Cheney says one of the biggest obstacles that remains to reducing driving is where people live. Seattle is an expensive city, and increasingly, she said, employees choose to live in far away areas with limited or no transit access. The next phase of the hospital's transportation demand management planning might involve trying to steer employees toward living nearby, or at least in areas well-served by transit.

"We’re looking at how we can influence where people live," Cheney said. "We attract people from all over the world to come work at Children’s. We’re interested in developing some resources and strategies about how to help them decide where to live."