Some places just talk about prioritizing transit and walking over highway construction. But Akron, Ohio, is putting its money where its mouth is.

The Akron region will spend more money this year to reduce road capacity than to add it, according to Jason Segedy, head of the Akron Metropolitan Area Transportation Study, the regional planning organization. Of the 39 projects approved for funding this year, the largest is $5 million to decommission a portion of State Route 59, the Akron Innerbelt Freeway.

That project will account for 17 percent of AMATS's 2014 budget. That is a portion of the 74 percent of AMATS's budget is being spent on maintaining existing roads, while 14 percent will go toward adding bike and pedestrian infrastructure. And 12 percent will go to projects that add road capacity.

That's not an accident. Leaders at AMATS are deliberately attempting to control the size of the region's road infrastructure -- and for good reason. At the height of Akron's reign as the center of the American rubber industry, the city had almost 300,000 residents. Today, the home of Goodyear Tires is down to less than 200,000.

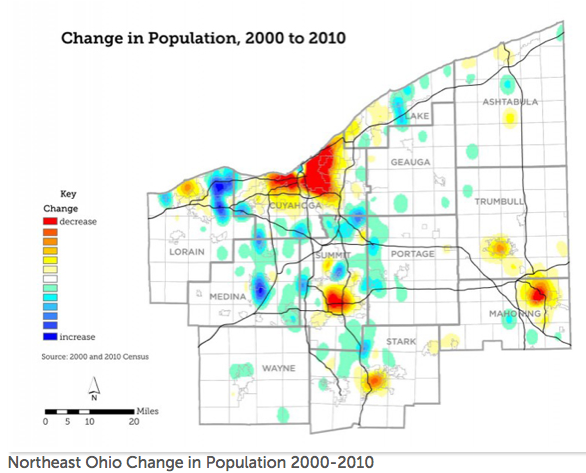

Although many Akronites have moved to the suburbs, the whole of northeast Ohio is losing population as well. The area, which includes Akron, Cleveland, and Youngstown, peaked in the 1970s, and has declined 7 percent since, according to recent research from the Northeast Ohio Sustainable Communities Consortium, the region's sustainable communities planning effort.

But even as the region bled population, it continued to expand its highways. Northeast Ohio has added 323 highway lane miles since 1990, even though the regional population continually declined, according to NEOSCC.

Most shrinking regions haven't yet come to the same realization Akron has -- that continuing to expand its infrastructure in the face of declining population and revenues is a recipe for disaster.

Segedy called this year's budget proportions "a start, in a shrinking region." "Maintaining the roads we already have and creating transportation alternatives are the highest priorities for Akron Metropolitan Area Transportation Study," he said.

AMATS uses a scoring process to rate projects submitted by local entities for funding. The way the process was designed, communities that submit projects to expand roads are at "a pretty big disadvantage," Segedy said, and they respond accordingly.

The Akron Innerbelt Freeway was a product of the old-school build-it-and-we-will-grow mindset. When it was built as part of the urban renewal era in the 1960s, local leaders predicted traffic would quadruple from 1947 levels. But what has actually occurred is closer to the reverse.

Akron's Innerbelt is notoriously underused. This six-lane, limited-access highway was designed to carry at least 100,000 vehicles a day. Instead it has been seeing a maximum of about 25,000, according to Segedy.

The road is aging too, and it's in need of costly repairs to bridges and ramps. Akron's longtime Mayor Don Plusquellic first came up with the idea to remove the highway more than a decade ago, after visiting Milwaukee and seeing the work being done to tear down the Park East Freeway.

The city hopes to leverage this first $5 million investment to decommission the sunken highway completely and redevelop the roadway. AMATS's contribution will help repair the service roads along the stretch closest to downtown. Eventually Akron wants to use the service roads exclusively to carry traffic through the corridor, while seeing if investors will be interested in using the roadway space for development. It hopes to develop the area into a biomedical corridor. That would leave about two dozen acres newly open for development between downtown and the city's west side. Akron is seeking money from the state and other sources to complete the project.