Philadelphia’s Route 47 bus snakes along narrow, one-way streets down nearly the entire length of the city. It starts about a mile from the house I grew up in (just on the other side of the city boundary) and ends just north of the ballparks in South Philly. Along the way, it stops on every single corner.

Not surprisingly, it’s one of the city’s most congested bus lines. Even running just six minutes apart, the 47 buses get so full they pass up more customers than any other line. The line also had the biggest time difference between its midnight runtime and its peak runtime.

That made it a perfect test case for a Transit First partnership between the city and the transit agency, SEPTA. The committee had existed since the 1980s but stopped meeting in the early 2000s when the partnership eroded due to years of resentment and mistrust among its members.

But with the administration of Mayor Michael Nutter, and his appointment of Rina Cutler as deputy mayor of transportation and utilities, the Transit First committee was revived. And they didn’t want to get bogged down in little fixes -- they wanted to see if they could make low-cost changes that would measurably improve service. In 2011, they implemented a pilot program along the southernmost 2.5-mile section of the 47 bus route, from Market Street in Center City to the end of the line at Whitman Plaza.

I talked to Philadelphia city planner Ariel Ben-Amos about the pilot earlier this week at the Transportation Research Board annual meeting, where the city and SEPTA were presenting their findings.

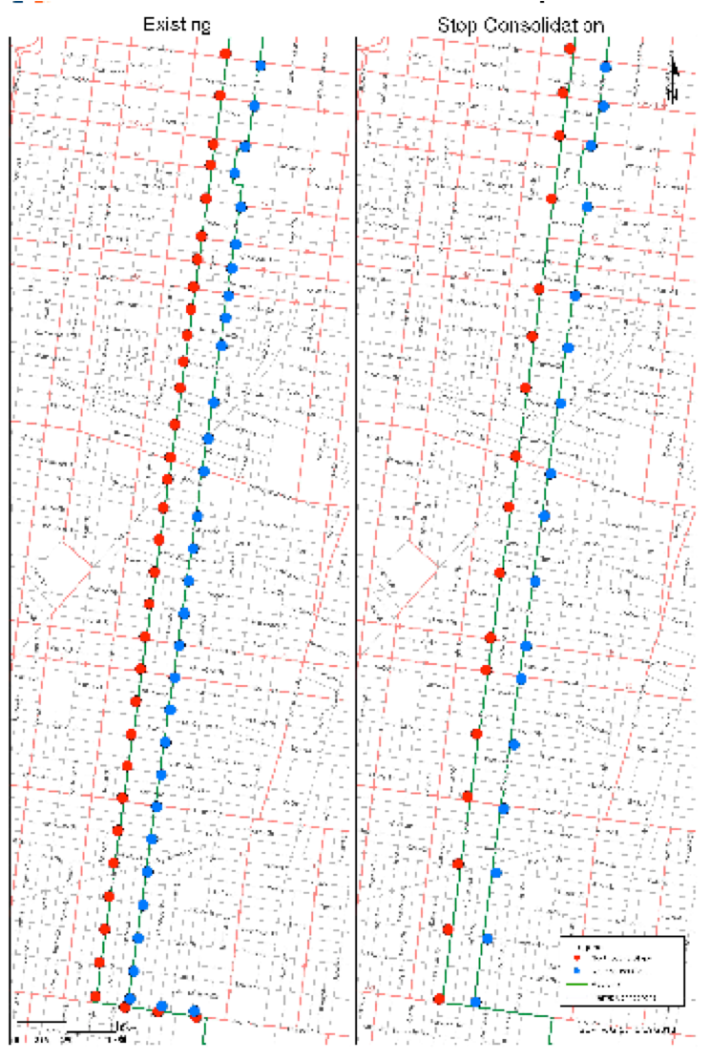

- Though “stopping every block is in many ways a venerable Philadelphia tradition,” according to Ben-Amos, they decided to consolidate half of the stops to save time. The blocks are short enough that riders still wouldn’t have to walk too far, and they were careful to eliminate the lower-ridership stops. Such an effort in Los Angeles had found that a 10 percent reduction in the number of stops yielded a 1.3 percent reduction in running time. Just yesterday, Eric Jaffe at Atlantic Cities spotlighted a story by News 1130 in Vancouver on research “showing that eliminating some bus stops ‘reduces travel times significantly without drastically affecting the number of people served along a route.’" Given the time savings from decelerating and accelerating, it would appear to be a winning strategy for the 47.

- They also switched from timepoint scheduling to headway scheduling, meaning that instead of arriving at a certain time, the bus should arrive six minutes after the last bus.

- By leveraging the partnership with the city, they were able to re-route sanitation trucks, which would block buses on narrow streets during peak hours.

- They switched three stop locations from the near side of the intersection to the far side, allowing the bus drivers to clear the light before they open the doors for passengers.

- At one especially busy intersection in each direction, they implemented a low-tech solution for all-door boarding by hiring a “rear-door loader,” stationed at that stop all day, to collect fares.

- They added a short-turn bus for the busiest section during the morning peak.

If they could save six minutes, they reasoned, they could add another bus to the schedule, since they ran on a six-minute headway.

But somehow, the pilot fell flat. All those innovations failed to improve performance. In fact, performance got worse.

They had 16 performance measures but the ones that really mattered were runtime, headway maintenance, and bunching and gapping.

- Runtime did improve by 1:27 (roughly 2 percent) in the northbound direction but actually got worse in the southbound direction, increasing by 10 seconds. At peak times, the effect was even more pronounced, with 1:37 time savings northbound and an 11 second added delay southbound. “This is important since the pilot focused on these directions and times of day,” the report said. Although they did get some northbound time savings, they clearly wouldn’t be able to add another bus. And the southbound deterioration of service was perplexing.

- Headway maintenance didn’t fare much better. Even though they were shooting for six-minute headways, they considered the buses on-time if they were anywhere between three and 10 minutes apart. Before the pilot, they met that goal 49 percent of the time; during the pilot, just 40 percent.

- As would be expected when headways are so uneven, bunching and gapping also got worse. Indeed, severe gapping, where headways stretched to at least double the scheduled six-minute gap, increased by 10 instances daily.

The city restored regular service, still scratching its head about where the pilot went wrong. They discovered some problems: First, conducting the pilot on only one section of a busy route didn’t make sense, since it couldn’t address problems happening elsewhere along the line. Signal delay was responsible for nearly all the delay during the pilot, something that SEPTA and the city’s efforts weren’t able to address. Adding transit signal priority could have made a big difference in the results, but it costs money, and the other changes they made were low- to no-cost.

“The urban environment has a far more significant impact on service than is easily quantifiable,” Ben-Amos said. “We eliminated stops but we still had stop signs.”

They also realized during the course of the pilot that some drivers were still stopping at eliminated stops for elderly passengers they had developed a relationship with.

Interestingly, though drivers reported a 34 percent decrease in customer pass-ups, customers reported a 4 percent increase -- indicating that perhaps they were waiting at stops that had been consolidated without realizing it.

Still, the city considers the first truly collaborative inter-agency effort to improve transit service in Philadelphia in many years to have been a resounding success. Simple things like changing stops wouldn’t have been possible without it, since the city dictates where the stops are, not the transit agency. Re-routing sanitation trucks is something else that requires cooperation with various agencies.

It restored the relationship not just between the city and SEPTA, but also with the public. “The true win of this was establishing a relationship of trust between the transit authority and its passengers,” Ben-Amos said. By publicly admitting that the experiment had failed and undoing the changes, they bought themselves the goodwill of the people they were trying to serve. And rather than admit defeat and stop trying to find ways to improve service, the pilot put them in a position to continue.

“We’re now planning and testing other pilots to implement,” Ben-Amos said, “and we can get political support for stop consolidation because we have a track record of sticking to our word.”

NOTE: Streetsblog won't be publishing Monday, in commemoration of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday. We'll be back to a normal publishing schedule on Tuesday.