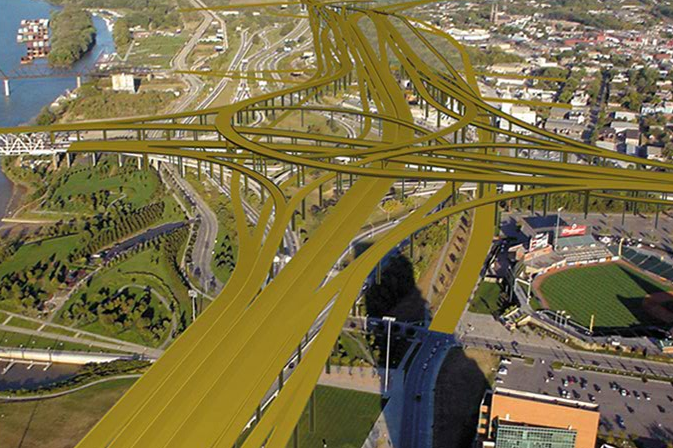

At $2.6 billion, the Ohio River Bridges project in Louisville, Kentucky, is the costliest in the state's history. It includes 18 elevated lanes, two enormously expensive bridges, a mammoth raised interchange, and a $225 million tunnel under an undeveloped suburban property ("Indiana's Big Dig").

For years, Louisville residents J.C. Stites and Tyler Allen fought for a more humane, down-to-earth solution. Their plan -- 8664 (short for "Remove I-64") -- proposed tearing down the elevated portion of the highway that stands between downtown Louisville and the Ohio River waterfront, to help integrate this mega-project into its surroundings. But it seems their fight may be over.

For a while it seemed Stites and Allen were getting somewhere. More than 11,000 people signaled support for the pair's highway-to-boulevard proposal at 8664.org. (This short video illustrates their proposed alternative.) Though the pair built a large grassroots organization to back the highway teardown plan, enthusiasm for the 8664 project never translated to political muscle.

"They crushed us," Allen says.

This week, on short notice, state lawmakers approved $753 million in bonding for the Ohio River Bridges project, which they hope to fund partly with tolls. The bonds were rated BBB, just barely investment grade. The project also expects to receive a $452 million federal TIFIA loan, according to Business First in Louisville.

Ultimately the fight to tear down and re-imagine the waterfront portion of I-64 fell victim to a political hornets nest surrounding the construction of the East End bridge. The 8664 plan hinged on the idea that this bridge would be built, but wealthy, suburban property owners in Jefferson County bitterly opposed it. These property owners unsuccessfully tried to use historic preservation to stop the bridge project, eventually obtaining landmark status for the 55-acre Drumanard property based on the fact that Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of landscape architecture, was once commissioned to plan the garden.

But even these well-connected property owners couldn't beat the Ohio River Bridges plan. Both bridges will be built. The most notable concession East End Bridge opponents won was the construction of a $225 million "tunnel under the trees" that would leave the Drumanard property untouched.

Allen and Stites say they underestimated how committed their opponents were to the bridge plan, and how many political allies they had.

"Pretty quickly it became clear that the mayor was adamantly against [8664] and that he had the local newspaper in his camp," said Stites. "We weren’t successful in convincing them that this was a compromise they should support."

Stites and Allen fought almost 10 years for 8664. The bridge project briefly stalled a few years ago, when officials didn't know where the $2.6 billion would come from. For a moment, it seemed like a turning point.

But things got moving quickly two years ago, once a plan was introduced to fund the bridges with tolls. The introduction of private funds also reduced the influence of citizens who opposed the project, Stites and Allen say.

"Ultimately, the reason the bad project took flight is they figured out they could pay for it with tolls," said Allen. "[At that point] it became totally underground, as far as the public process."

"The machinery of road projects is so hidden," he went on. "At least [you can] talk to the legislature. Then they handed if off to the tolling authority. You couldn’t even ask supporters to call them."

The construction of the Ohio River Bridges project means some of Louisville's up-and-coming urban neighborhoods like NuLu -- featured in New York Times coverage of the project -- will be separated by an enormous concrete barrier. The interchange portion of the project, joining three highways, is particularly massive. It was reduced from an original width of 23 lanes to 18 because of funding issues. But even at 18 lanes, it will be a 325-foot wide expanse, slicing through downtown neighborhoods.

Allen and Stites say they were in a difficult position from the outset, without any prominent political supporters. Unfortunately, that never changed.

"We were able to start a conversation about something that the system really wouldn’t let us finish," said Allen. "That’s pretty frustrating."