Urban streets serve a much different purpose than rural ones: They're for walking, socializing, and local commerce, not just moving vehicles. Unfortunately, American engineering guides tend not to capture these nuances.

That can lead to a lot of problems for cities. Wide roads appropriate for rural areas are dangerous and bad for local businesses in an urban setting.

But there's change on the horizon. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Engineers' "Green Book," the so-called bible of transportation engineering, has some new competition specially designed for urban places.

Last month, the Federal Highway Administration gave its stamp of approval to two new engineering guides: the National Association of City Transportation Officials' bikeway design guide, which features street treatments like protected bike lanes, and Designing Walkable Urban Thoroughfares: A Context Sensitive Approach, designed to help cities build streets that are walkable and safe for all users.

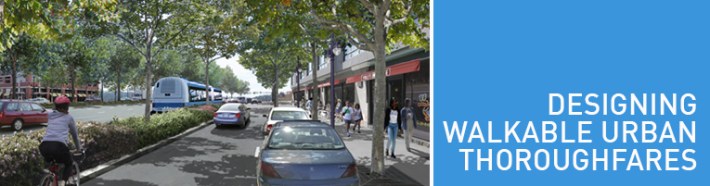

The urban thoroughfares guide, produced by the Institute of Transportation Engineers and the Congress for the New Urbanism, is based on the concept of "context sensitive solutions," which seeks to balance the movement of vehicles with other objectives, like promoting active transportation and fostering retail businesses. Both guides are now recommended by FHWA as companions to AASHTO's guide.

Jeffrey Tumlin, a consultant with NelsonNygaard and an adviser to the development of the urban thoroughfares guide, said the revolutionary thing about it is the engineering guidance about the important ways urban "arterials" differ from rural highways. Problems can arise when the Green Book is applied to cities because it is written by the organization of state DOTs, which are mainly concerned with highway building, not local streets.

"While AASHTO guidelines do accommodate a broad array of street designs, where they are weak is providing designers with information about the way in which local streets are very different," said Tumlin. "Engineers need more thorough guidance on the ways in which urban arterials are distinct from rural highways and ways in which to design those arterials to prioritize a wide variety of objectives."

The new ITE guide instructs engineers to "use performance measures that benefit all modes," and to consider the surrounding area -- the character of the community -- when designing streets.

The guide was developed over 10 years by ITE and CNU, with funding from FHWA and the EPA, and has been available for a few years. The city of El Paso, Texas, for example, has instructed its transportation engineers to use the guide on all city streets. FHWA's memo signals the first time it has been formally endorsed by the federal government.

Ian Lockwood, a livable transportation engineer and principal with AECOM, says AASHTO's Green Book already provides the kind of flexibility that allows engineers to do good projects that benefit urban environments. But this new guide could push a more innovative approach to livable streets.

"Efforts like this are ways to interpret the AASHTO guidelines and related guidelines to make it easier to do something a little more enlightened," he said. "This raises awareness; it gives people examples. It gives them what we call 'cover.' If engineers start to follow them, they can say it’s endorsed, bona fide."

CNU says the fact that the guide was published by a relatively conservative group -- the Institute of Transportation Engineers -- strengthens the case that great urban street designs are safe and tested.

"FHWA's statement puts the ITE Street Guide front and center on every traffic engineer's desk." says CNU Director John Norquist. "This is exactly what we hoped would happen."