How should we grade America's transportation systems?

The big, headline-grabbing transportation metric right now is the Texas Transportation Institute's Urban Mobility Report, which holds up the lack of congestion as the ultimate sign of a well-functioning transportation system. By that measure, cities like Kansas City, Phoenix, and Detroit -- where car commutes can be free-flowing but tend to cover long distances -- come out looking great, while large metros that do a better job of providing non-automotive transportation options -- like Chicago, Washington, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York -- look like failures.

But TTI's narrow focus on congestion has come under increasingly intense scrutiny in recent years, with critics pointing out that it is used to justify road-widening projects that purport to reduce congestion but mainly serve to encourage sprawl and lengthen commutes.

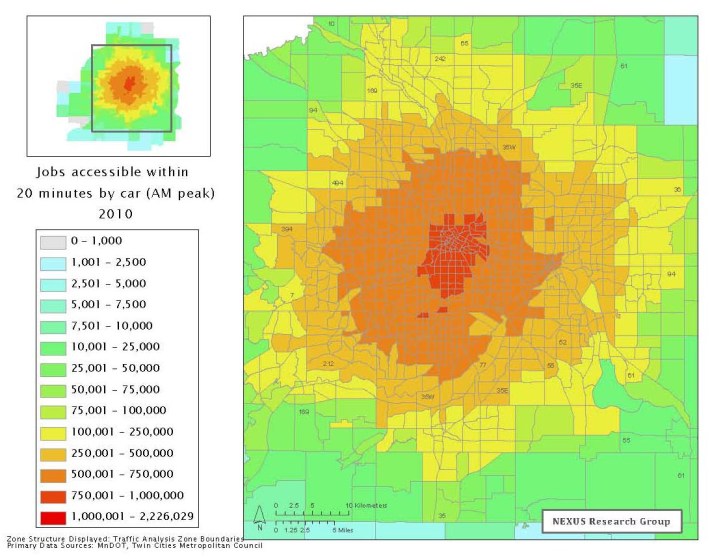

A study recently released by the University of Minnesota presents an interesting alternative to the TTI's metrics. UMN Transportation Engineering Professor David Levinson recently analyzed metropolitan commuting according to a very different criterion: accessibility, or "the ease of reaching desired destinations."

Levinson attempted to improve on the TTI report by tracking the time it takes for people in the 51 largest U.S. metro areas to reach jobs. His findings stand in stark contrast to the TTI's report. Large metros like Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York and Chicago offered the greatest number of jobs within a 10-minute car commute, Levinson found.

While TTI's methodology penalizes cities for locating homes and businesses close together, because that increases congestion, in Levinson's analysis, higher concentrations of destinations are rewarded for helping to reduce travel times.

"There are two ways for cities to improve accessibility—by making transportation faster and more direct or increasing the density of activities, such as locating jobs closer together and closer to workers," Levinson writes.

"Accessibility is not a new idea," he adds. But his is the first study that uses it to systematically attempts to measure how different metro areas compare. The report focuses only on auto access, but the same concepts could be applied to walking, biking, or transit access, he says.

To measure accessibility, Levinson factored in average job density, the average speed of car traffic in the transportation network (from the TTI analysis), and the circuity of trips (how indirect they are). The analysis also looked at the number of destinations within 10-, 20-, 30-, and 40-minute "donuts" around the city.

Levinson found that his measure of "accessibility" is linked to a number of positive economic indicators. For example, he found that home prices in a metro area increase 0.23 percent with every 1 percent increase in accessibility. He also found that doubling accessibility leads to a 6.5 percent increase in real average wages.

There are environmental and quality-of-life connections, as well. Levinson found that a 1 percent increase in accessibility is linked to a 0.06 percent reduction in the share of commuters who drive. He also found that accessibility tends to be linked to shorter overall commute times. A 1 percent increase in "accessibility," he found, is correlated to a 90-second reduction in average commute time each way.

All of this suggests that prioritizing "accessibility" in transportation investment -- rather than alleviating congestion -- might be more economically beneficial for metro regions.

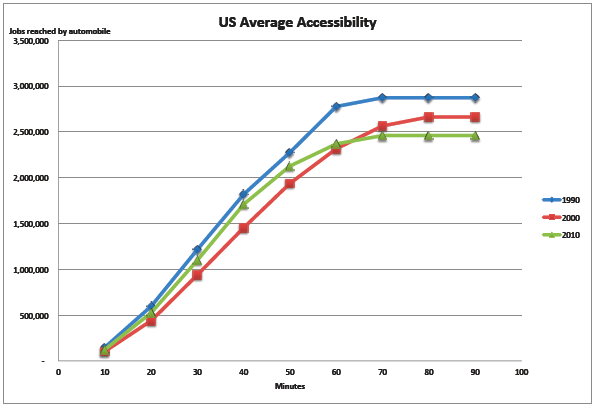

Levinson also measured how accessibility has changed in metro areas over time, finding that it has worsened in American regions overall, both since 1990 and since 2000.

Joe Cortright, an economist who works for the Brookings Institution, among other clients, conducted a critique of TTI's Urban Mobility Report for CEOs for Cities in 2010, finding that the report failed to capture how much time people actually spend commuting. Cortright said Levinson's work comes at an opportune time.

"It’s absolutely a step in the right direction," said Cortright. "It thinks about not just how fast you can travel but how much you can reach."

Cortright added that U.S. DOT is charged, right now, with developing performance measures to grade transportation agencies, as a result of the new transportation bill, MAP-21. If U.S. DOT were to incorporate a metric like Levinson's, rather than TTI's congestion analysis, it would likely lead to a greater emphasis by state and regional agencies on smart land use planning and less on widening roadways.