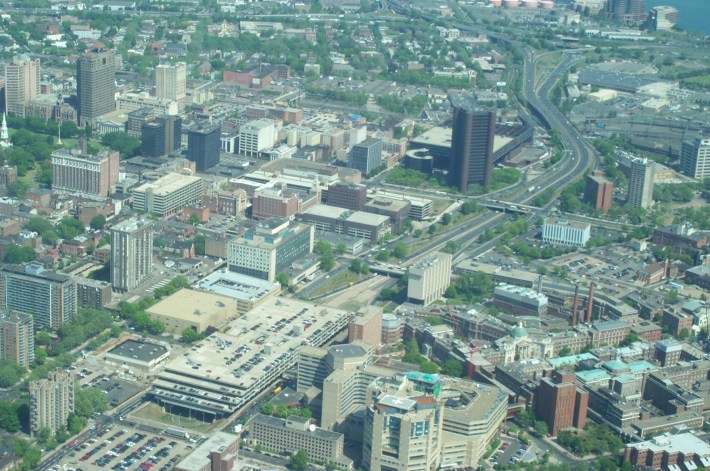

The "most defacing scar from the 1960's Urban Renewal era" -- that's how local advocates describe the Route 34 Expressway through downtown New Haven. Just about a year and a half ago, this small New England city won a TIGER grant to heal that scar. But another disfiguration may be growing in its place.

The city's plan to dismantle about one mile of the road in 2016 was sold as a way to open up 11 acres of downtown land to development and increase walkability and connectivity. But local advocates are sounding the alarm that it's starting to look like 1960 all over again. Instead of reclaiming urban fabric from car infrastructure, New Haven is dangerously close to replacing one urban freeway with another urban freeway.

Last week an independent group called the New Haven Urban Design League issued a scathing, 30-page report titled "A Highway Rebuilt, Not Removed" [PDF]. In it, the League -- one of the biggest proponents of the highway teardown -- says the city of New Haven should scrap its current plans to build a partially grade-separated, limited access roadway and begin the process from scratch, with a public planning process.

"Essentially, the highway is being re-configured and re-built rather than removed," the report states. "We don't feel that $30 million in public funds ... should be used to create a plan that fails."

The problems with the existing plan are many, the League says. The plan contains two four-lane roads, less than a block apart -- an "eight-lane monstrosity," according to Norm Garrick, a transportation specialist at the University of Connecticut.

The plan doesn't add any cross streets, obliterating any claims to improving the street grid. Furthermore, much of the new roadway design would be sunken below grade, portions of which the League claims could create an "even more formidable barrier to connectivity than the previous formation."

The idea to tear down Route 34 began with a push from the Urban Design League in 2004. After a series of public meetings, the organization, working with other advocacy groups, was able to win city support for the tear-down concept, plus $5 million for engineering studies. But the actual planning phase was held up by a peculiarity of Connecticut state law. The planning process had to be put on hold for a year and a half while the regulation was revised.

Meanwhile, Carter Winstanley, a prominent developer and owner of a local biomedical firm, hired a design team and developed a plan of his own. The plan centered around the construction of a large office building to house his firm -- complete with a 800-space parking garage (which would add to a 2,600-space structure nearby) -- in the existing highway trench. At first the city said it was out of the question, said Anstress Farwell, president of the Urban Design League. After all, the public had been completely left out of the planning process.

But city officials changed their tune when the TIGER program launched and the feds started offering millions for "shovel-ready projects." The city took up the Winstanley plan and won $16.5 million to make it a reality.

Farwell was surprised that the Winstanley plan, with all its shortcomings, won the highly competitive grant.

"There's an astounding amount of parking in this area,'" she said. "We thought, 'How could they even look at a project that has an 800-car garage attached to a 2,600 car garage?'"

Meanwhile, City Hall has been less than responsive to public misgivings about the plan. The League organized public workshops last summer to gather ideas to improve the plan, but so far they haven't swayed officials to adopt changes.

The Urban Design League says even without eliminating the Winstanley building and parking garage, the plan could still be salvaged if "adequate traffic, transit, market and environmental studies" are conducted and the remaining portion is reworked with the project's original goals in mind. But time is running out. Under the terms of the grant, the city needs to obligate the funds for the project by September of this year.

"This is public land. I think you really have to engage in a public process, you really have to work with the intelligent desires of the public when they come out to public meetings," said Farwell. "We're not going to have this opportunity again."