This month’s bipartisan deal on the MAP-21 transportation bill in the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee hinged on a compromise to make major changes to the popular and successful Transportation Enhancements (TE) program, which primarily funds projects for biking and walking. The final deal eliminates dedicated funding for TE, instead making a smaller amount of money available for funding bike/ped -- and a host of other activities --under the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement program’s “Additional Activities” category (CMAQ-AA).

TE, which previously received a dedicated 10 percent cut of all Surface Transportation Program funds ($878 million in 2010), will now be competing with Safe Routes to School and the Recreational Trails Program (the other major pots of previously dedicated bike/ped funding) as part of CMAQ-AA, which will be funded at TE’s 2009 level of $833 million. (Note that although TE received 10 percent of all STP funds, it constituted less than two percent of the entire federal transportation program.)

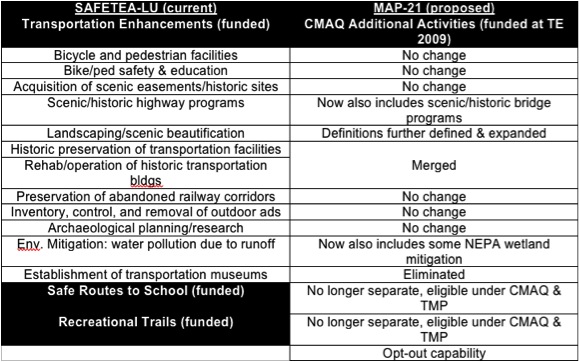

In an even more dramatic shift, bike/ped-averse state governments will be able to opt out of CMAQ-AA altogether. The chart below, which distills a document published by America Bikes [PDF], illustrates the changes, project type by project type:

Running CMAQ Up the Flagpole…

Under the new system, most bicycle and pedestrian projects are still eligible for TE funds. What's noteworthy are the other categories of projects that are now eligible, or not. Transportation museums are thrown out of the program, while eligibility is expanded for landscaping, environmental mitigation, and scenic and historic bridges. It’s some of those expansions that worry Jesse Prentice-Dunn of the Sierra Club, who told Streetsblog that projects like wetlands management—while obviously important as a matter of environmental stewardship—could squeeze out some bicycle and pedestrian projects. However, he applauds the last-minute decision to remove HOV lanes, another expensive category of projects, from eligibility under CMAQ.

“Overall, we really want this bill to construct a planning and funding process that enables projects to advance on their merit, particularly, in our opinion, [projects] that can reduce dependence on oil,” said Prentice-Dunn. “This bill can be a way to break that addiction.”

Still, he cautioned that any new transportation bill will need to be assessed on the basis of two things. First, funds should continue to be dedicated—or at least reliably disbursed—to non-motorized transportation projects, given the historical bias favoring automobiles. Second, project selection criteria should be altered in order to ensure that non-motorized projects have a shot even without dedicated funding from programs like TE. The changes in the Senate bill, then, signify a step backwards on dedicated funding. There's no indication that other aspects of the bill would compensate for that setback by establishing criteria that reward investment in active transportation.

…But Who Will Salute?

What would these changes mean for bike/ped projects on the ground or in planning stages? Price Armstrong, program manager for MassBike in Boston, says he can’t overstate how important TE funding has been. Armstrong points out that Massachusetts, ranked ninth among states for bike-friendliness by the League of American Bicyclists, is one of the few states to have adopted a statewide Complete Streets policy. However, the progress in Massachusetts was not accomplished in a vacuum:

Massachusetts has made a lot of progress just over the past five years, partially on its own but significantly thanks to the federal contribution to its bike/ped projects through TE, CMAQ, and Recreational Trails Program dollars. In a cash-strapped environment, even in a bike-friendly state, active transportation projects are the first to get shelved. Since the [U.S.] Senate, which is controlled (barely) by more bike-friendly Democrats, proposed a 20-30 percent reduction in funding, an opt-out clause for states, and increased the competition for the funding, we are extremely concerned.

Armstrong specifically cited the Bay State Greenway as one project currently underway that could suffer substantial setbacks as a result of the changes to TE. Such difficulties are likely to beset the larger projects first, according to Dr. Joseph Hacker, the manager of Transit, Bicycle, and Pedestrian planning at the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission in Philadelphia: “The scale of projects may shift from desire lines on maps [i.e. sweeping statewide visions] to more local initiatives… Advocacy is going to have to change to projects which are possible rather than big picture ‘bicycle highway’ planning.”

Hacker added that while some states may opt to flex all their funds to road projects (Montana or North Dakota), and some metropolitan areas with nascent bike movements could be drowned out by rural interests at the state level (Georgia or Pennsylvania), other states might devote their full share to bicycle funding (Colorado or California).

“A stronger local case is going to have to be made regarding the benefits of new bike/ped projects in order to garner funding,” Hacker said.

The Storm Before The Calm?

The aversion of many states to funding active transportation only makes the job of implementing bike/ped projects that much harder. As one possible immediate adjustment, the League of American Bicyclists’ Darren Flusche suggests, “Advocates should be getting DOTs to fund as many of these projects as possible, as soon as possible, because we still don’t know what the future holds.”

The “increased flexibility” touted by the authors of the Senate bill essentially gives states an easy way to "opt out" of the program. The new provision allows states to drag their feet on spending the money, only to be rewarded for their tardiness by not having to use those funds for their intended purposes. “This could really set the clock back on all of the progress towards a more bicycle-friendly America we’ve made in the past 20 years,” said Flusche.

Flusche says that his organization and others like it will keep the pressure on Congress in the meantime. Their aim will be to convince lawmakers of the value and importance of protecting active transportation projects before MAP-21 becomes the law of the land. Afterward, advocates will shift their focus from Congress to states and local governments, as Flusche and Dr. Hacker predict, with many implications yet unknown.