In 2004, Salt Lake City faced a challenging question: How do you fit 1.4 million additional residents into a region hemmed in by mountains on the east and water on the west? In the course of solving that problem, the city ended up answering several other head-scratchers, like: How do you get buy-in for smart-growth policies from conservatives wary of urbanism? And, how do you make new greenfield development both sustainable and wildly popular?

At the Rail~Volution conference last week, Andrew Gruber, executive director of the Wasatch Front Regional Council, showcased the transit-centered solution that’s now propelling development in Utah’s capital city.

If official projections are right, the high quality of life and thriving economy of the Wasatch Front could invite population growth of more than 65 percent by 2040.

If the region continued along current growth trends, Gruber explained, it would add more than 300 square miles of development to meet the housing and commercial demand by 2040. Vehicle miles traveled would nearly double, from 49 million to more than 90 million per day, by 2030. By 2020, the cost of new infrastructure could balloon to more than $26 billion.

In just a few decades, a region known for its open space and outdoor lifestyle would be a mighty congested and costly place to call home.

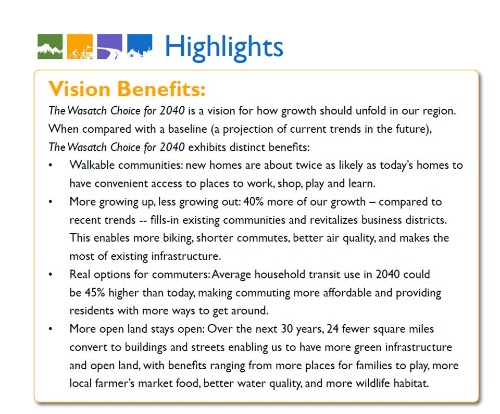

So, in 2004, the state’s two largest MPOs came up with a comprehensive plan for growth and development in the four-county region. "The Wasatch Choice for 2040" prioritizes housing and transportation choices — and earned a $5 million Sustainable Communities Planning Grant from HUD in 2010.

Now, Salt Lake City is investing more, per capita, in new public transit than any other metro area in the country, and exporting ideas to the rest of the country.

Starting in 2005, citizens and planners in the Wasatch Front evaluated different scenarios for growth, looking at the long-term consequences of each development pattern. Perhaps surprising for such a conservative state, the consensus that emerged included a set of progressive growth principles focused on efficient infrastructure, transportation and housing choice, and coordinated planning.

By following those guidelines, Wasatch Front residents could look forward to benefits like an 18 percent reduction in congestion (compared to the baseline projections).

The focus on town centers and TOD isn’t just a selling point for baby boomers and Gen Y professionals who are looking for walkable, urban neighborhoods. It also placates conservative Utahans, who don’t want the government encroaching on their lifestyles with newfangled sustainability mandates. “Not everybody wants to live in a town center. That’s fine,” Gruber said. “But if we can develop in a more concentrated way, with new homes and jobs in town centers, we’re preserving the character of existing neighborhoods, too.”

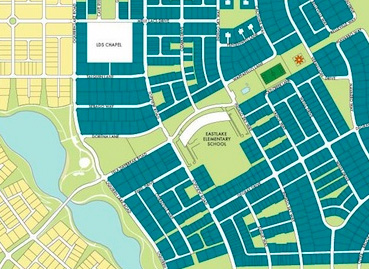

One model of this approach is the new Daybreak development, just southwest of Salt Lake City. “This community was planned with transportation choices in mind from the very beginning,” Gruber explained. A rail line extending from downtown has two stops in the mixed-use development. The community design prioritized sidewalks and walkability, organizing the streets in a connected grid that makes it easy to get from Point A to Point B without having to navigate a maddening maze of cul-de-sacs that seem to go in circles.

Those simple principles have had a dramatic impact on how residents get around the mixed-use neighborhoods. For instance, in Daybreak, an incredible 88 percent of kids walk or bike to school, compared to just 17 percent in other neighborhoods in the region.

And folks are lining up to live there. In 2010, the National Homebuilders Association named it Community of the Year, and this year, real estate consulting firm Robert Charles Lessor recognized the development as the 11th best-selling community in the country. “Daybreak is the most successful housing development in the region, and one of most successful in the country,” Gruber said. “It’s not that everybody wants to live in this type of development, but there’s a demand out there that’s not being met… This is a model for greenfield development done in smart, sustainable way.”

Salt Lake City officials have also coordinated housing and transit policies in the urban core, as well. In recent years, the region has made big investments in public transit. The per-capita investment in transit over the past 10 years is the highest of any region in the nation, according to Gruber. Since the first TRAX light rail line opened 10 years ago, three more lines have debuted, including two just last month, as well as a commuter rail line to the north. A commuter rail link to the south and a TRAX line to the airport are set to open in 2013.

The commuter and light rail systems meet at an intermodal hub on the west end of downtown Salt Lake City, in an area that the mayor described as a “derelict, downtrodden piece of our city.” The city is trying to change that by encouraging infill development near the transit hub, but for now, it poses some challenges.

“There’s a dead zone between the hub and the rest of downtown that’s impeding people’s desire to use the transit system,” Gruber said. “Right in that area, we’re doing a mix of uses — housing, commercial and retail — and using streetscaping to try to make this area a vibrant, vital area that people want to come to. So we’re using transportation as a catalyst to redevelop an under-developed area and enhance the use of the entire region’s transit network. This one project downtown benefits the entire region.”

The work in Salt Lake could also benefit cities around the country. As part of its HUD grant, the Wasatch Front Regional Council is using its experience to help other governments and citizens overcome two major barriers to sustainable development: lack of information and antiquated zoning requirements.

On the zoning front, the council is working on a form-based code that doesn’t splinter development into commercial areas and residential areas. “It focuses on the form of the building, instead,” Gruber said. “So, in a particular area you might want two- to three-story buildings with a certain set back from the streets, and whatever the market will bear is OK, as long as it fits the character of the neighborhood… That model will be available to folks across the country.”

Officials are also developing free, open-source technology that will help planners and empower advocates to make more informed choices about their communities’ development. The “Envision Tomorrow +” tool allows stakeholders to “paint in different scenarios” for growth and development, Gruber says, and see how it impacts important metrics like energy consumption, air quality, tax collections and return on investment. “It will allow more people to come to the table with good information and evaluate scenarios at the local level,” he said.

Art Guzzetti of the American Public Transportation Association praised Salt Lake’s progress. “What you’ve done in that region over the past decade,” he told Gruber, “is just extraordinary.”