In the vein of several other recent reports that have highlighted significant transportation reforms that can be made now, with or without a reauthorization bill, the EPA has published guidelines for states and MPOs to make livability plans a reality [PDF]. They illustrate how using performance metrics can lead to better-designed transportation networks, especially when it comes to livability.

The EPA focuses on 12 important indicators that transportation agencies should be measuring:

- Transit accessibility

- Bicycle and pedestrian mode share

- Vehicle miles traveled per capita

- Carbon intensity

- Mixed land uses

- Transportation affordability

- Distribution of benefits by income group

- Land consumption

- Bicycle and pedestrian activity and safety

- Bicycle and pedestrian level of service

- Average vehicle occupancy

- Transit productivity

The EPA recommends a range of tools familiar to urban planners and reformers, like scenario planning and performance monitoring.

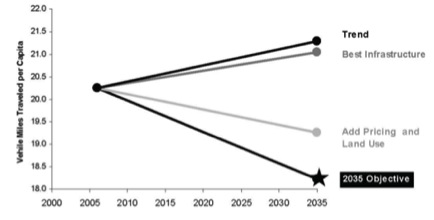

It acknowledges in the fine print that in some places, lack of data is still an obstacle to adequate performance measurement – especially on issues that DOTs are less likely to invest in, like bicycle mode share. Meanwhile, everyone collects data on VMT, for example. And when San Francisco established their performance measures through a planning process like the ones recommended by the EPA, they discovered just how far they were from their objective -- even if they put ideal conditions in place:

You don’t decide to start measuring transit access through long-range planning and corridor studies without having a goal in mind, though, and the EPA has several. It seeks to “protect natural resources, improve public health, strengthen energy security, expand the economy, and provide mobility to disadvantaged people" by improving states’ accountability for making sure these livability measures are implemented.

Speaking of transit access: the guidelines get specific about how to measure access, explaining that access is determined by establishing how many jobs, residents, trip origins, or trip destinations are within a ¼- to ½-mile radius of a transit stop. And getting even more detailed, the EPA spells out exactly what those measurements should be:

- Share of population with good transit-job accessibility (100,000+ jobs within 45 minutes).

- Number of households within a 30-minute transit ride of major employment centers.

- Percentage of work and education trips accessible in less than 30 minutes transit travel time.

- Percentage of workforce that can reach their workplace by transit within one hour with no more than one transfer.

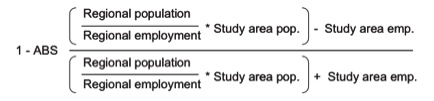

Determining success in mixing land uses is a little more complex. It goes a little something like this:

Follow all that? Yeah, me neither.

Performance measures, as a tool for getting the most value out of what we spend, are working their way into the mainstream discourse on transportation, embraced (at least rhetorically) by both sides. Planning, on the other hand, is still seen by many conservatives as the occupation of coneheaded urbanists, always trying to rein in man’s wild nature (which, I suppose, is to drive SUVs in exurbia).

Getting specific about how planning can be used to hold government accountable for its spending – and how those tools can help improve out health, economy, and environment, as well as our traffic throughput – could be a big step forward for transportation reform, even if Congress never passes a reauthorization bill. And by the looks of it, “never” sounds about as reasonable a timeline as anything else.