The summary of the House Transportation Committee’s reauthorization bill – no legislative text has been released yet – includes several provisions for “streamlining” project delivery. While on its face, a little streamlining could help reduce excessive delays and bring costs in line, environmentalists are concerned that underlying the “streamlining” provision is a desire to gut environmental review processes and stifle public input.

The Senate bill outline revealed today also addresses streamlining, but gives fewer details. It says that it will "reduce project delivery time and costs while protecting the environment" by using "innovative contracting methods; creating dispute resolution procedures; allowing for early right-of-way acquisitions; reducing bureaucratic hurdles for projects with no significant environmental impact; encouraging early coordination between relevant agencies to avoid delays later in the review process; and providing incentives for accelerating project delivery decisions within specified deadlines."

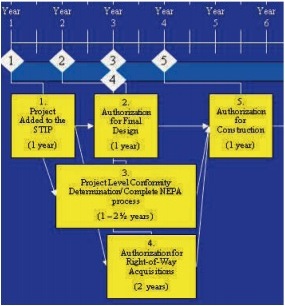

The House bill, on its face, is far more obsessed with accelerating project delivery. Nearly every section of Committee Chair John Mica’s bill has a part about streamlining. He has a chart about how concurrent, not consecutive, project development phases can make a 15-year process into a 6-year process for completing a project.

Most projects don’t take 15 years under the current system – in this case, Mica is holding up an extreme and unusual example as the norm. There’s room for improvement in the current system, but perhaps not as much as Mica indicates.

One of the principal places Mica seeks to save time is by shortening the environmental review process (known as NEPA, for the National Environmental Policy Act that mandated such reviews). But, in 2001, only three percent of transportation projects underwent a NEPA review at all. Even if, theoretically, that number has doubled in the decade since then, only a tiny percentage of projects undergo a full NEPA review. Those that do require a NEPA review tend to be the large, landmark projects which do, by their size and complexity, take more time to complete.

The process the GOP sets out could end up working at counter-purposes with the goal of streamlining. They propose to do all reviews, including NEPA, concurrently with the design and right-of-way authorizations. But that concurrency assumes that nothing substantial comes up in the review process that needs to change the design or the right-of-way. Certainly, there’s nothing “streamlined” about having to go back to the drawing board once a project is fully authorized because of issues that could have come up at the very beginning.

Indeed, SAFETEA-LU encourages transportation agencies to seek the participation of the environmental community early on, in order to reduce time delays and conflict later. Why spend all that time designing something that won’t pass muster?

Mica is also suggesting hard deadlines for agency reviews of projects, and the bill says that failure to meet the deadline would result in a default approval. “We don’t think that’s a responsible way to speed up the process,” said Jesse Prentice-Dunn, transportation policy analyst for the Sierra Club.

Some complex projects are simply going to take longer, said Kathryn Phillips, a transportation policy expert at the Environmental Defense Fund.

“If you’re talking about a 100-mile stretch of six-lane freeway going through a pristine area, it’s going to take more than 30 to 60 days,” Phillips said. “What if it takes longer because the things that are encountered in the review are so complex? Are we then just going to throw out the review?”

Besides, she said, many of these agencies are so underfunded they simply don’t have the capacity to work any faster than they already are. Indeed, Phillips said, underfunding is a primary reason for project delays.

“There are years and years between a project being added to the STIP (State Transportation Improvement Program) and it actually getting built because there isn’t any money – NEPA or no NEPA,” Phillips said. “The problem here is not NEPA, the problem here is money. And what is it [Mica] is proposing? A bill that is less than the current SAFETEA-LU!”

California has managed to speed up its environmental review process by taking the NEPA review in-house and doing the reviews at the state level. We reported before that “in order to be allowed to do this, states must have environmental protection laws that are at least as stringent as federal ones.” In addition to California, four other states were approved to take on their own environmental reviews under SAFETEA-LU: California, Alaska, Ohio, Oklahoma and Texas. They’re not necessarily the states that have the most rigorous environmental protection records, but their members of Congress were in key positions at the time the bill passed.

Those states haven’t accepted the authority, however, because if they took over the responsibility of the reviews they would be liable in court, not the federal government. Some states have argued that the feds should still be liable, even for decisions made by states, but so far that’s not the case.

Another potential hazard of Mica’s bill is that it “classifies projects in the right-of-way as categorical exclusions under NEPA,” meaning that as long as you’re not claiming new land, there’s no reason to investigate the environmental impact of what you plan to do on that land. That leaves open the option of highway widening or replacing rail lines with car lanes without any review.

“How do you address long term air pollution and climate impacts?” Phillips said. “It might be that the right-of-way is already so disturbed it won’t impact wildlife or water -- but how will it impact air quality?”

Many environmentalists worry that under the guise of “streamlining,” House Republicans are actually just trying to gut long-standing environmental protections. “NEPA has been a bedrock environmental law for decades,” said the Sierra Club’s Prentice-Dunn. “It’s helped reduce the impacts of transportation and infrastructure projects. Now is certainly not the time to go backwards in terms of protecting our environment.”