“Transit alone is insufficient to make a real estate market,” said Dena Belzer, the president of Strategic Economics, an urban design consulting firm. Her group is a partner in the Center for Transit-Oriented Development (CTOD), which this week released a new report on the effects of transit expansion on real estate markets.

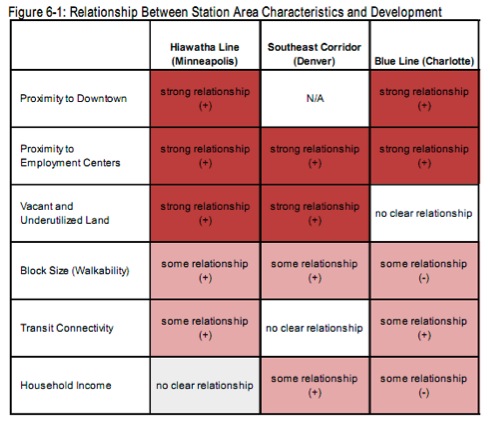

Transit won't, on its own, create a booming market for compact, mixed-use development, but if a city has a good, walkable grid and simply needs better access to jobs and centers of activity, it can do wonders. "There are sites where you can see that opening up access just really 'popped' things," Belzer said. For the best chances of success, you need to use transit to connect underutilized land with walkable downtowns and employment opportunities.

The new CTOD report, “Rails to Real Estate: Development Patterns along Three New Transit Lines” [PDF], picked corridors in the Southeast (Charlotte, NC), the West (Denver, CO) and the Midwest (Minneapolis) to see how transit affected development patterns.

The big success story was Charlotte’s Blue Line – where transit “popped things,” as Belzer said. It’s the newest of the three lines, having just opened in 2007, at the height of an ongoing real estate boom. (It went bust along with the rest of the country, and all the big investors pulled out, but until that happened, everything was going great.)

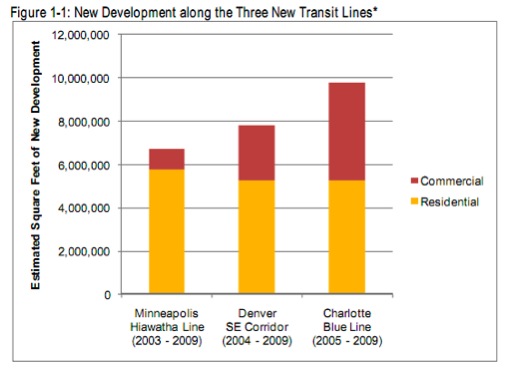

Even in that short timeframe, this corridor saw the biggest spike in development after the opening of the transit line – nearly 10 million square feet of new development, compared with 6.7 million in Minneapolis and 7.8 million in Denver – and that’s along a rail line that’s only half as long as Denver’s (though tightly packed with 15 stations, compared to Denver’s 14).

Charlotte was destined for greatness because the city aligned its transit along all the right places, according to Belzer.

“Charlotte was much more intentional about pairing these infrastructure improvements with the line and placing their stations in locations that would be accessible and enhance development opportunities,” she said. Light rail was built in the midst of a housing boom where demand was focused on high-density housing.

The biggest factor, Belzer said, was that “the line itself went through neighborhoods that were ripe for development.” Even so, that corridor didn’t develop evenly. Most of the development occurred in the downtown district, with some in the South End, an old manufacturing area. “Once it got into places with a more suburban development pattern – less street connectivity, the line is elevated and the stations are no longer at ground level – you see very little impact. The development activity drops off.”

A pedestrian-friendly street grid is a defining quality of places where TOD flourished. In addition to financing light rail, Charlotte voters have approved bonds for station area infrastructure like streetscaping and sidewalks.

That was where Denver came up short. The Southeast Corridor runs along I-25 and I-225, linking suburbs with office jobs. Given that the line follows a highway, and that stations are located in areas without a walkable street grid, perhaps it’s not surprising that development was more dispersed than in Charlotte, with much of it happening on greenfield sites. “The accessibility value there came from the highway,” Belzer said. “Transit was just frosting on the cake.”

The authors do speculate, however, that the transit line’s greatest impact may have been in the design of the new projects and a greater mix of uses.

Of course, transit is often built in places that have already experienced a significant degree of development, where there isn’t always room for much more. Belzer pointed to Denver’s West corridor, under construction now, where several of the station stops are being built in well-established, densely developed neighborhoods. “And there isn’t much opportunity for new development there,” Belzer said. “In that case, the opportunity is to have people who live in that neighborhood be able to use transit, and not have to own a car. So pedestrian connectivity would be a more important thing to focus on – it’s not about reframing a real estate market or enhancing development. It’s just about making a tighter connection between the land use and the transit.”

Minneapolis’s Hiawatha Line is the oldest of the three case studies, having opened in 2004. At the time, skeptics noted that the new light rail line would only go from the airport to the Mall of America and downtown – a benefit for tourists and businesspeople but not the majority of city residents. Regardless, ridership has far exceeded expectations. In fact, the 30,500 average weekday trips already exceeds Metro Transit’s goals for the year 2020.

Most of the new development that came in with the Hiawatha rail line was in the form of downtown condos and apartments – very little commercial development occurred. In some places outside of downtown, the relative inaccessibility of the stations from the neighborhoods meant that not all the station areas saw property values go up, as transit was less integrated into the neighborhood.

“There are still opportunities for infill development on sites in Minneapolis,” the report states, “many in neighborhoods with a need for better streetscape, pedestrian connections and other ‘placemaking’ investments.”

To date, most transit-oriented development has occurred in or near downtowns or major employment centers, according to the authors, in part because those places allow for “investments in neighborhood infrastructure and amenities [that] are critical for unlocking the potential for TOD, especially in areas where land use patterns were previously automobile dependent.”

The report is especially useful for localities looking to finance transit using value capture, a strategy by which the private sector, anticipating economic benefits and increased property values, helps pay for a new transit line. Value capture is tricky business, and having some added clarity about when TOD takes off – and when it falls flat – is enormously helpful for developers and planners.