Editor's note: a version of this article originally appeared on Urbanism Speakeasy and is republished with permission.

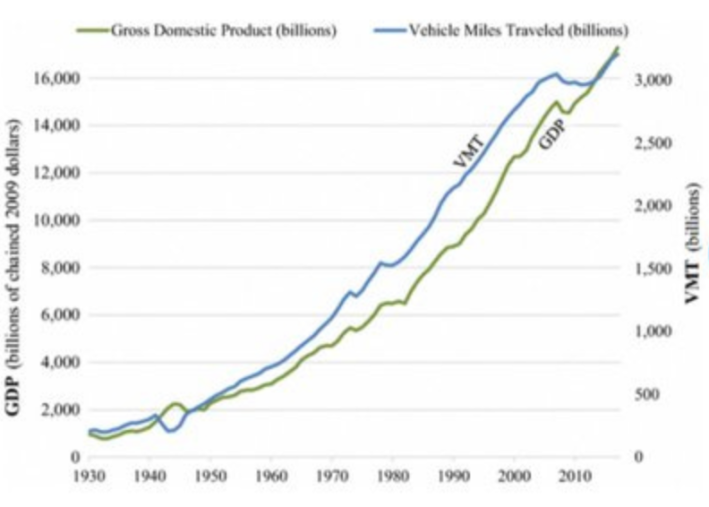

Motordom's defenders will frequently overlay vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and gross domestic product (GDP) as if the story must be "more driving equals more prosperity."

It's used in lazy attempts to prove road expansions for motor vehicles are necessarily good while traffic calming, road diets, bike lanes, transit lanes, etc. are bad. I do think the VMT/GDP overlay is an interesting talking point, but not in the way it’s generally spun by my fellow keyboard warriors.

Obviously, personal automobiles have expanded our reach incredibly and are a wildly important invention. There were periods when disadvantaged or outright hated groups of people had no convenient way to find work. Access to personal cars gave them point-to-point mobility.

But economic growth doesn't depend on all of us driving more. GDP doesn't tell the dirty details of the car-dependent lifestyle most of America is burdened with.

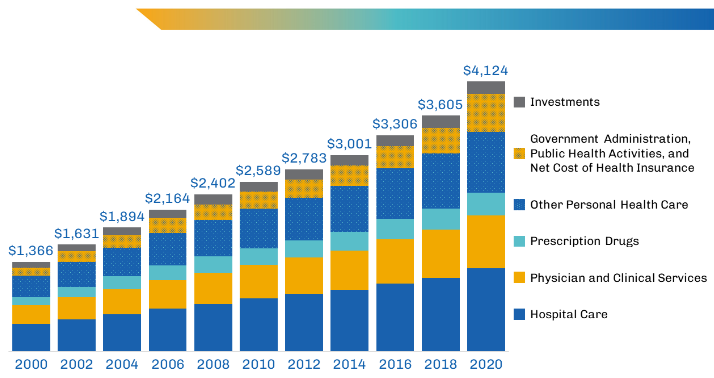

In 2020, U.S. health care costs grew 9.7%, to $4.1 trillion, reaching about $12,530 per person.1 At the same time, the United States lags far behind other high-income countries when it comes to both access to care and some health care outcomes.

—Association of American Medical Colleges Research and Action Institute

The United States has one of the most expensive healthcare systems in the world. Every dollar spent on healthcare services—from hospital stays to doctor visits to prescription drugs—is included in the GDP.

The more people get in life-altering crashes, the more they spend on healthcare, and the higher GDP goes. In 2019, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reported that motor vehicle crashes cost American society $340 billion, with medical expenses constituting a substantial portion of this total.

A 2021 study by the CDC, meanwhile, estimated that the economic cost of injuries in 2019 was $4.2 trillion, which includes $327 billion in medical care expenses. That’s all injuries, not just traffic, but important to understand it’s part of our GDP.

The obesity rate in the US has grown from 12% in 1975 to 43% in 2024. The CDC has estimated that annual obesity-related medical care costs nearly $173 billion (type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and other chronic conditions). Annual nationwide productivity costs of obesity-related absenteeism range between $3.38 billion and $6.38 billion.

The economic impact of obesity in the U.S. is profound, affecting healthcare systems and workforce productivity. But if you want to treat rising GDP as always a good thing, then these costs are good for society.

VMT rises out of necessity, not as a marker of genuine growth or wealth.

High inefficient land use and planning naturally drives up VMT, because it gives people no choice but to drive everywhere for everything. Car-oriented infrastructure increases transportation expenses like building and maintaining roads, buying or renting cars, and fueling, maintaining, and repairing our household vehicle fleets. A simplistic economic take would be that sprawl is good for GDP.

This year’s Your Driving Cost (YDC) study reveals that the total cost to own and operate a new vehicle is $12,297 or $1,024.71 monthly, an increase of $115 from 2023.

—American Automobile Association

There are countries that have managed to build strong economies with a much lower VMT per capita than the US. They have transportation systems that allow people to reach destinations with minimal car travel by taking advantage of sidewalks, bike lanes, and buses.

Of course, the underlying land use assumption is that a mixture of land uses is permitted. You might look at our soaring VMT trend as a reflection of disastrous land use and housing regulations rather than a direct sign of progress.

So by all means, continue to look at cultural and economic trends. But don't stop with vehicle miles traveled and gross domestic product. Look at sedentary lifestyles, physical activity, heart disease, obesity, chronic illness, depression, anxiety. Look at the costs of each family having to be a fleet operator. Look at whatever other factors come to mind.

The point is, if you're on the side of human flourishing, dig into the GDP to see how money is spent in the economy. You'll spot some startling costs that come with being dependent on motor vehicles.