The fines that are generated by automated traffic enforcement fill some cities' coffers, but they may not be delivering the scale of street safety benefits we need— and they are definitely creating inequitable financial harm to vulnerable communities, a provocative new study says.

“There is little evidence” that automated traffic enforcement is an effective tool at either “improving traffic safety [or] limiting violent interactions between law enforcement and drivers during minor traffic stops ... when enforcement is predicated simply on the assessment of financial sanctions," the group Fines and Fees Justice Center argued in its report.

That statement might raise the hackles of some street safety advocates, many of whom have been inspired by the much-documented success of New York City’s speed camera program and the movement to reduce interactions between armed police and human road users.

Its authors, though, say mobility justice advocates must consider the nuances of how camera systems are used in unique communities — and not ignore other solutions that will make streets even safer.

“We all want safer streets,” said Tim Curry, policy and research director for the Fines and Fees Justice Center. “But there's kind of a knee-jerk reaction to use automatic traffic enforcement to get there. There are a lot of problems with that which we need to at least be discussing, even if we can't always agree on what to do about it.”

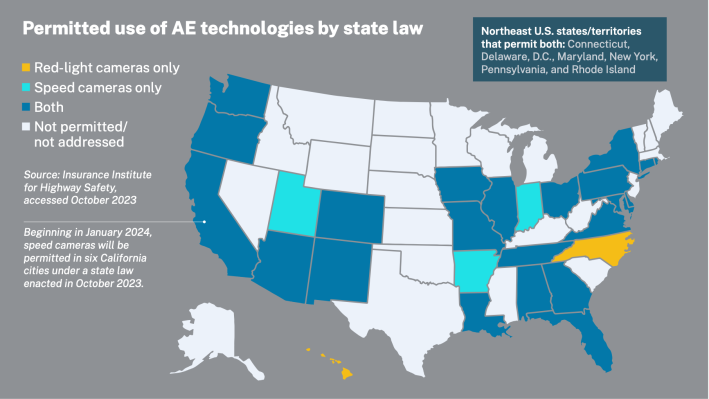

Curry argues those important discussions aren’t always happening, even as camera enforcement proliferates across America. Between 2012 and 2022, the use of speed camera programs alone increased 40 percent, with other communities introducing legislation to allow other forms of automated enforcement, like red light cameras, noise cameras, school bus stop arm cameras, and more.

Many of those programs have been pushed as a less-dangerous alternative to in-person police stops on the road, but the report authors say there’s little evidence that they’ve actually reduced contact between cops and road users, who police continue to stop for other crimes.

“Because the U.S. Supreme Court has held that pretextual traffic stops are constitutional, even if the true purpose of the officer is to engage in other types of investigation, automated enforcement does not stop officers from profiling Black or Brown drivers and targeting them for traffic-based stops,” the report said. “Instead, the expansion of automated traffic enforcement simply creates a new and more effective way to fine exponentially more people.”

Of course, supporters of automated enforcement might argue that cameras have done something else pretty significant: saved lives in avoided traffic crashes.

Curry acknowledged that speed cameras have been shown to reduce collisions 20 to 37 percent, and that red light cameras at least reduce some crash types — including injury crashes. But the effectiveness of other kinds of automated enforcement hasn’t been comprehensively studied, he said — and no study has conclusively determined that steep fines themselves drive safety, as opposed to the simple presence of cameras alone.

Meanwhile, some studies have shown that roadside signs that sense and display a car’s velocity are enough to get motorists to reduce their speed by 30 to 50 percent for those driving more than 10 miles over the posted speed limit, even if there’s no threat of a financial penalty attached — and hard infrastructure like road diets and roundabouts, of course, are even more effective at encouraging safe driving.

It would be one thing, of course, if automated traffic enforcement were being used to raise money for infrastructure change, eventually rendering cameras unnecessary. Curry argues, though, that even some of the most robust programs in America haven’t done that, citing Washington D.C. and Chicago, which have come to rely on cameras to plug holes in the general revenue stream.

He even argues that camera revenue may itself create a perverse incentive to keep designing dangerous roads — and keep fining drivers who may not even know they’re exceeding a limit that’s set far lower than the design of the road suggests.

“A big part of the theory of [crime] deterrence is immediacy,” added Curry. “And getting a ticket weeks or months after the fact may not have that immediacy to create long-term behavior change. … What an automated traffic fine is, fundamentally, is an after-the-fact financial penalty that we hope may slow you down next time — whereas engineering changes will slow people down in the moment, before they can hurt somebody. That’s true safety.”

Even if cities do dedicate automated fines to infrastructure, Curry argues that road users shouldn’t have to wait for reckless drivers to rack up tickets and hurt people in crashes before their transportation leaders build infrastructure that’s all but guaranteed to slow them down.

“Infrastructure changes should be funded by something that’s stable,” he added. “By treating them as a line item that is only funded through — or is primarily funded through — automated traffic enforcement, we're creating a dependence on that money.”

Of course, safe streets advocates who have fought for changes for years may be doubtful that transportation leaders will ever find allocate sufficient resources for safe infrastructure without installing a camera to actively collect it through fines. Because cameras themselves often cost more than hard infrastructure, though, Curry doesn’t accept the argument that ATE is a financial necessity — especially when you factor in the ongoing maintenance and supervision required to keep a camera program running. The FHWA, for instance, estimates that installing speed humps cost between $1,000 and $8,000, with only occasional maintenance costs as the roadway surface degrades in a few years; a recent New York City audit, by contrast, found that its speed camera program spent $4,000 in maintenance fees per camera.

Other supporters argue that cameras are better in the short term because they are faster to install than serious infrastructure improvement. But Curry dismisses that notion, too, given how well tactical urbanist approaches can work.

“It doesn't always have to be the giant roundabout,” he said. “There's a lot of low-cost things that communities are finding success with, like painting streets to create the illusion of narrower lanes. … If you’re looking for something that's short term that we can do right now, there are alternatives to fines.”

The report also offers a devastating take on the regressive nature of automated fines, which cause far more harm to low-income motorists than wealthy ones, even though the danger each poses to his neighbors is the same. And it also notes that fines are often not enough to deter rich motorists from dangerous driving.

“A $200 ticket to one person is nothing, and a $200 ticket to another person is life altering,” he added. “And how that plays out is often racialized. … I haven't seen a significant study that suggests that increasing the fine increases the rate of deterrence at all. I know plenty of people, unfortunately, who see a traffic fine as the price of doing business. But for other people, one or two traffic tickets is the difference between eating or paying your rent.”

In addition to scaling fines to income and eliminating associated fees, Curry and his co-authors recommend that cities treat automated enforcement as a temporary tool as officials build more holistically safe places. And that means demanding more from the engineering, education, and emergency services layers of the “safe systems” safety net — and making sure that equity doesn’t get overlooked.

“We hear a lot in traffic safety circles about the ‘four E’s,’” he added. “But the only ‘E’ that everyone seems to talk about is enforcement. … But we can't punish our way out of most public policy problems."