On a weekend vacation not too long ago, a few friends and I climbed to the top of a six-story building and looked out over what may soon be one of the most bikeable regions in North America.

More specifically, we'd gotten to the top of that building — known locally as the Ledger – without getting off our bikes once, thanks to a wide ramp that wraps around the entire structure and lands visitors on a rooftop patio overlooking Bentonville, Ark. with its maze of slow neighborhood streets and off-street bike trails, as well as the long sweep of the Ozark mountains reaching into downtown.

The Ledger was lauded as the first "bikeable building" in the world when it was completed earlier this year, but the northwest Arkansas region it overlooks is seemingly working to become something even more novel: not just the mountain biking capital of world, as they've been dubbed by its local tourism office, but the biking capital of America, period, and an unlikely model for communities across the U.S.

To say that journey has been unusual, though, would be bit of an understatement. As recently as 20 years ago, bike paths barely existed anywhere in Arkansas, much less in northwestern cities like Fayetteville and Bentonville, which have historically been better known for housing the headquarters of auto-centric Fortune 500 companies like trucking conglomerate J.B. Hunt, chicken processing monolith Tysons, and Walmart. Like countless car-dominated communities around the country, though, locals say northwest Arkansas — or NWA, as some Arkansans call it —have always had a latent appetite for active transportation. They just didn't have anywhere safe to ride.

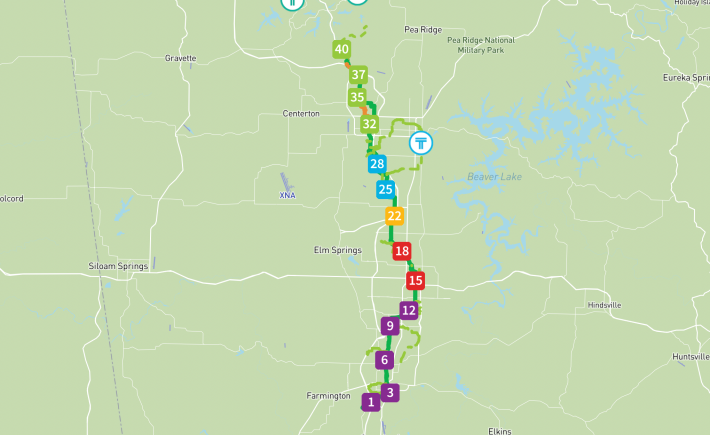

That slowly began to change sometime around 2011, when the Walton Family Foundation and a coalition of regional governments began working together to make invest in bike infrastructure. Their efforts began with handful of single track trails for mountain bikers, eventually expanding into a $30-million matching grant from the Foundation that helped secure the federal money necessary to complete the Razorback Greenway, a massive, 37-mile multi-purpose trail connecting seven distinct cities.

In the years since the initial route of the Razorback was finished in 2015, it's grown by an additional four additional miles, and bike projects have popped up on ballot measures across the region to connect residents to that strong spine. Collectively, those efforts have snowballed into a sprawling, 500+ mile network of trails built to serve everyone from cyclocross pros to workday commuters and little kids — a pace is particularly astonishing considering that no city in the area has more than 100,000 residents, and especially when compared to the glacial progress of bike infrastructure building in larger metros.

"Being from the middle of the country, there's [traditionally been] a lot of car-centric focus in towns like this," said Nelson Peacock, president and CEO of the Northwest Arkansas Council, an economic development agency in the area. "But [biking] really started taking off from that Greenway. Now, in pretty much every city, whenever they do a bond issue, it's replete with cycling: building the infrastructure, getting protected lanes, doing more to make it easier to get around. ... Now, you go to the store, and you'll see several people on a bike; even if you're out driving, you'll see people cycling on the trails [and you'll see] bike shops everywhere. And I think that [ubiquity] just breeds into people that you need to give it a shot, because it's so easy here."

Of course, some critics might say that NWA's success came too easily, and that it's not exactly replicable in U.S. communities that don't have access to deep-pocketed donors.

After all, the philanthropic outfit that helped fund many of the region's trails is itself funded by the single richest family in America — yes, those Waltons, who are less known nationally for their passion for building bikable cities than for building massive parking lots outside their namesake megastores. As the popular narrative about northwest Arkansas' cycling revolution goes, two of the outdoorsier heirs to the Walmart fortune — Sam Walton's grandsons Tom and Steuart — developed a deep love of cycling as a sport while at college in Flagstaff, Ariz. and Boulder, Colo., respectively, and decided to bring it back to their Ozark hometown, eventually transforming the larger region into a Disneyland for their personal hobby.

Peacock says that narrative, though, drastically over-simplifies what's actually been a complex, multi-decade biking push with many stakeholders involved besides the Walmart heirs — and that it especially ignores how residents have embraced biking for transportation and recreation alike.

The Razorback Greenway was in the works as far back as the early 2000s, when the Walton grandsons were still teenagers, and its proponents worked hard for decades to overcome skepticism from the state DOT and some community-members to keep the project alive. In many ways, the Waltons' biggest impact may have been simply accelerating the construction of the regional bike network by giving leaders with vision the funds they needed to design it around their constituents' needs — and without that local buy-in, none of the trails would have probably ever broken ground.

"Obviously, the funding helps," he adds. "But [the Walton Family Foundation] doesn't build any trails that the cities don't agree to maintain. ... You never want to discount resources, but leadership, I think, and sharing a vision, has really been what propelled things forward."

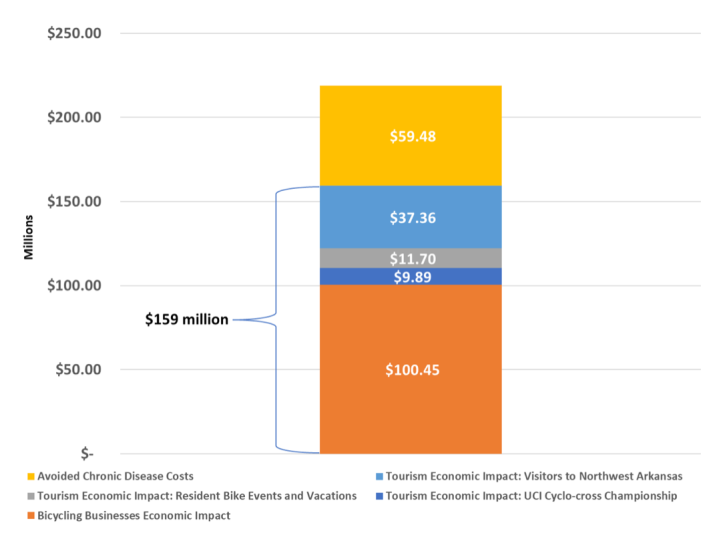

Representatives from the Foundation itself stress that their bicycling initiative has always been about making life better for Arkansans with trails, events, and programs of all kinds, not building pump-track playgrounds for billionaires. Tom Walton himself has spoken openly about the importance of building "safe streets [that] make it possible for kids to get around without their parents driving them all the time," and Peacock stresses that the Foundation doesn't fund projects that locals don't want or can't afford to maintain independently. That, seemingly, hasn't proven a problem so far; one recent study shows the NWA biking ecosystem has generated a whopping $159 million in economic impact, between tourism, the success of bicycle-oriented businesses, avoided public health costs, and other factors. (To be fair, like a lot of things in NWA, the Waltons funded the university that conducted the study.)

"It’s really been a key part of our effort to improve quality of life and continue to make Northwest Arkansas one of the best places to live in the country by making it as vibrant and inclusive as possible," said Robert Burns, director of the Walton Family Foundation's Home Region project. "We want people to feel comfortable getting their kids to school, to a workplace, to the store, no matter how they get around, and we want everyone to be able to [access these things] right from their neighborhoods."

In addition to matching federal grants for hard construction costs, Burns says much of the foundation's money has gone to critical (and often under-funded) "soft" costs that can make or break even the most modest bike lane — and can make the difference between a top-down project that alienates locals and one that inspires a groundswell of grassroots support.

"Philanthropy has the ability to set really ambitious goals and help our partners meet those goals, even when they’re stymied because of funding, or bringing stakeholders together," he adds. "Philanthropy can help regions be courageous; we can help accelerate a timeline, catalyze a project with some front-end risk support, do pre-construction examination that a city might be reluctant to invest in. And we can really help expand community engagement. ... We're always looking for creative community engagement strategies beyond just, 'Come to City Hall.'"

That community focus is a palpable dimension of the riding experience in Northwest Arkansas, even if it's harder to capture in photographs than action shots of stunt bikers flipping off ramps in the woods. As an avowed non-mountain-biker and relative wimp, I can attest that many of the trails I rode in Bentonville and Bella Vista were relaxed, paved paths that winded their way through short stretches of placid forests and landed you straight at the doorsteps of bike-oriented coffeeshops fliers with advertisements for family bike events, or stunning (yes, also Walton-funded) museums with ample racks out front. I saw way more toddlers on Striders and elders on e-bikes than speedy athletes on hardtails‚ though, notably, natural space is so easily accessible in NWA that even the most hardcore MTB enthusiasts I spoke to had biked straight from home to a nearby trailhead, rather than loading their bikes up in a car.

That's not to say that northwest Arkansas is exactly Amsterdam West. Most of its biggest cities rank around the 80th percentile of PeopleForBikes' annual city ratings, and during my most recent visit, many trail segments were still under construction. Dangerous arterial roads lined with strip malls and highway ramps are still very much a reality, as are freight trucks emblazoned with the names of the big corporations that dominate the region. Bentonville technically only completed its first protected, on-road bike path last year, but many of the city's downtown multi-modal trails perform a similar function of separating people from cars entirely, because they run through under-utilized spaces between and behind buildings where drivers aren't permitted to travel. These routes feel humble, safe, and like something that we should theoretically be able to build in just about any neighborhood in the country, if developers would cede just a few extra feet of backyard.

Peacock acknowledges that bike infrastructure is far more politically difficult to retrofit into established U.S. cities than it is to build in growing metros that are adding 36 new residents a day and building brand new homes all the time. And with cycle-friendly cities in seriously short supply across America, he also acknowledges that places like NWA are at risk of the kind of rapid gentrification that could put biking out of reach of the people who live there today. Burns stresses that housing affordability has become another major priority for the Foundation, and that "protecting people who have been here for multiple generations" is an ongoing goal; Peacock estimates that 55 to 60 percent of people living in NWA today weren't born there, and says that for better and worse, the region's bike infrastructure has become a recruitment tool for corporations looking to lure workers out of the car-dominated "rat race" in big cities like Austin and L.A.

"We do have a lot of work to get some of our minority populations on the bike, to get them out riding," he adds. (A recent report found that Hispanic riders were under-represented relative to their share of the NWA population, while Asian, Black, and Indigenous cyclists were only slightly over-represented.) "We need to do better in multiple languages to get different groups out on bikes, and we know that by doing that, everyone will be healthier and more active. And so those are some of the next steps that we've got to take."

If NWA can successfully navigate those challenges, though, the region could become a model not just of how much can be done when private philanthropy sees the benefits of bike infrastructure to meet their larger goals, but how they can work together with bold, forward-thinking governments to reimagine communities quickly.

And for Peacock, it's already a prime example of how quickly bike culture can take root if its given the resources and visionary leadership it deserves — though he doesn't pretend that NWA didn't have a serious leg up.

"Northwest Arkansas has a lot of natural assets that helped spur this along the way," he adds. "But I think you can look to us as an example of a culture shift. If you can just give everyone a little taste of what it's like to have these alternatives, [you can show them] that you're not stuck doing one thing all the time. [What I'd say to] any town is, 'The next time you're doing a bond initiative or making some investments, start small and build out from there.' And I think over time, you'll change the culture."