Editor's note: a version of this article originally appeared on PeopleForBikes and is republished with permission.

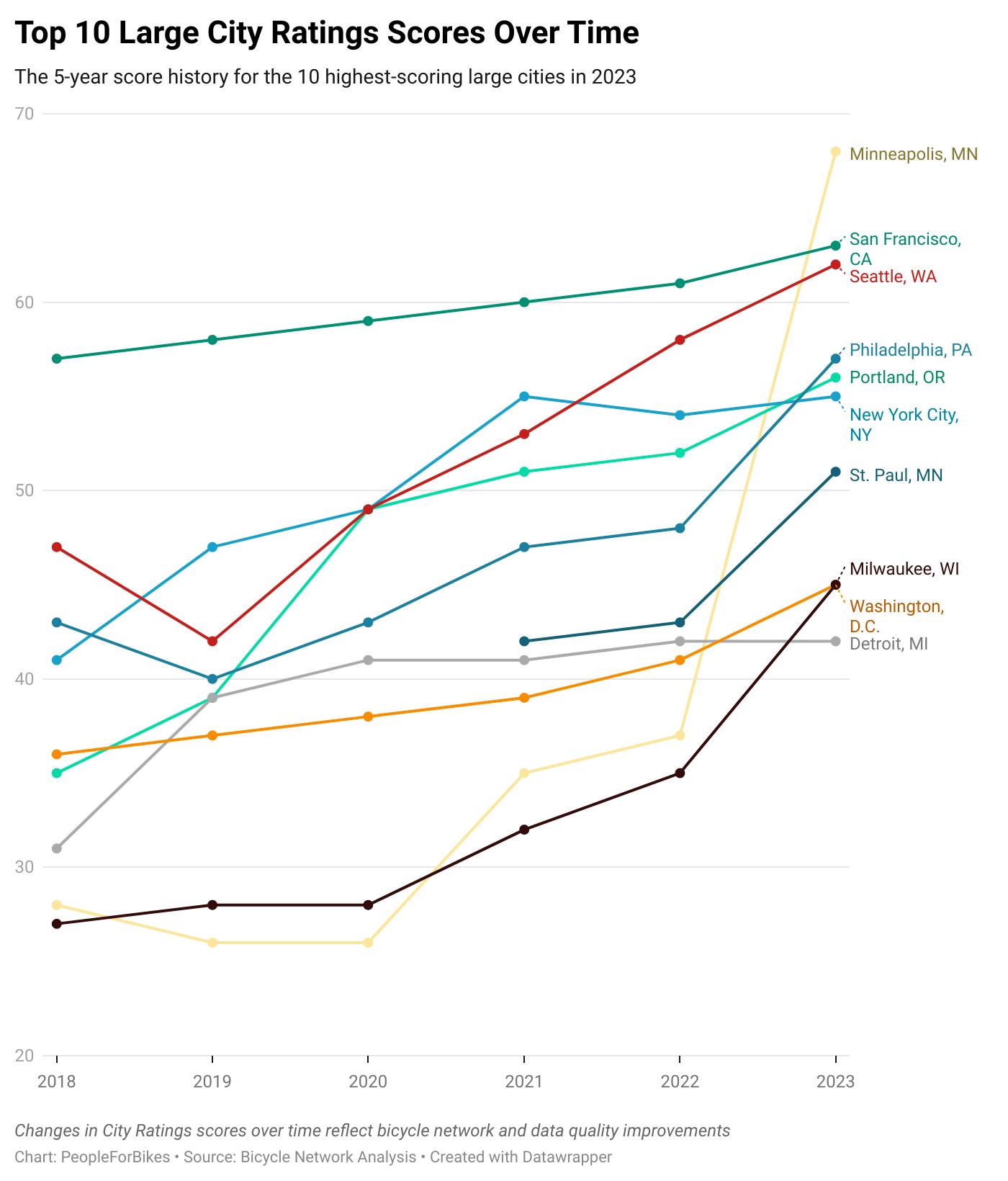

For the first time since our City Ratings program launched seven years ago, Minneapolis, Minnesota, tops the list of the best large U.S. cities for bicycling with a score of 68. In 2022, the city’s score hovered in the 30s, and its leap to number one speaks to a number of notable changes.

First, Minneapolis’ data received a massive update — and while that’s not the most exciting reason, it is essential to their success. Our scoring system is informed using data from OpenStreetMap, which is essentially the Wikipedia of street maps, meaning anyone can edit it. If a city’s data in OpenStreetMap doesn’t adequately reflect the breadth and/or quality of the city’s on-the-ground infrastructure, then its corresponding City Ratings score will be lower. Thanks to updates to its OpenStreetMap data, Minneapolis saw its score rise.

That being said, the midwestern city, home to a population of about 425,336 people, has also made huge strides in building out the safe, connected bicycle infrastructure that demands OpenStreetMap updates — and defines the world’s best places to ride.

“What's really unique about Minneapolis — what's different than many of the other notable cities for bicycling in North America — is that the backbone of our network is probably one of the best urban trail networks in the country,” says Luke Hanson, a senior transportation planner for the city. “Minneapolis' status as one of the top cities for bicycling is both a combination of strategic multimodal investments that include that kind of urban trail network, as well as deliberate complimentary policy guidance over time. Those pieces go hand in hand to create our current bike network.”

A key component of Minneapolis’ cycling urban trail network is the Grand Rounds Scenic Byway, a continuous, 51-mile loop of off-street bike trails that traverses the entire city. For more than 100 years, the byway has been a recreational and transportation resource for people biking, walking, and rolling — a historical network that the city has been able to build off of over time with strategic and complimentary investments primarily along former rail corridors. That includes the Midtown Greenway, the Cedar Lake Trail, the Hiawatha LRT Trail, and the Dinkytown Greenway, which are all repurposed, grade-separated trails that avoid conflicts with motor vehicles and connect some of the most important destinations in the city.

“All of this has been augmented by a series of initially painted buffered bicycle boulevard facilities throughout the city that provided network-level connectivity,” says Hanson. “More recently, many of these facilities have been improved by transitioning them from traditional unprotected bike lanes to protected facilities in a variety of different design types, utilizing things like protected intersection design and other tools we have available to us.”

Hanson is quick to point to the various policies that have helped Minneapolis develop one of the country’s most robust bicycle networks: its 2011 Bicycle Master Plan, 2013 Climate Action Plan, and 2015 Protected Bikeway Update to the Bicycle Master Plan. The 2015 plan outlined a long-term objective of creating 174 miles of protected bike lanes as part of the city's bike network. In 2019, the city also conducted a neighborhood greenway study to look at ways to transition traditional bike boulevards to make them more comfortable, safer, and more appealing to a wider group of people. Finally, the city’s 2020 Transportation Action Plan provides policy guidance to continue implementing protected and safe bike facilities throughout the city.

Minneapolis currently boasts 21 miles of on-street protected bike lanes and 106 miles of off-street sidewalk and trail miles. By 2030, the goal is to have 141 miles of newer, upgraded all ages and ability bikeways throughout the city, along with a micromobility mode share of 10% (the Climate Action Plan outlines a long-term goal of raising the bicycle commute mode share to 15%). Unfortunately, the loss of the city’s Nice Ride bike share system earlier this year complicates that vision (and is arguably a huge oversight on the part of the city).

“[Mass mode shift] is still a goal and it’s important to work towards that even with the challenge of not having a reliable bike share system,” says Hanson. “What we're trying to establish is a complimentary transportation network where people have options beyond just driving and single occupancy vehicles. In addition to transit, we're thinking through walking, biking, rolling, and other methods to make sure people have transportation options and choices to help us get to those mode shift goals. Marketing is important but we’re reinforcing that with infrastructure.”

Other complementary policies, such as redesigning intersections and reducing speeds, play an equally important role. In 2020, Minneapolis and its twin city St. Paul lowered their default speed limits, switching from 30 to 20 mph on residential streets and 25 mph for larger, arterial, city-owned streets. Lowering speed limits aligns with Minneapolis’ Vision Zero workby reducing the likelihood of crashes and the likelihood of a crash leading to serious injuries or death. Since lower speeds are critically important in places where people are walking, rolling, and biking — which is most locations in Minneapolis — they correspond with higher City Ratings scores.

“Lowering speed limits is a tool but we're also using street design to compliment those lower posted speed limits,” says Hanson. “Traffic calming measures such as raised crossings, speed humps, speed cushions, medians, and narrowing roadways are equally important. Even if they’re not explicitly a bike project per se, they make it safer and more comfortable for people to bike.”

Other things Minneapolis is doing well include leveraging federal grants to fund projects, taking advantage of street resurfacing projects to upgrade infrastructure, and creating a brand new Street Design Guide. According to Hanson, in addition to providing guidance on what an all ages and abilities bikeway should look like, the guide also includes guidance on when to install them (the short answer: on any major throughway undergoing reconstruction). Notably, the city also eliminated parking minimums and made the choice to transition away from single-family housing, choices that contribute to better cities for cycling (it also helps that Minnesota is progressive when it comes to its state transportation policy).

“It's not as simple as the silo of transportation infrastructure — these things build upon one another to make a functional, practical system for people to rely on and use,” says Hanson. “It’s important to acknowledge that there are a lot of additional projects that aren’t bike-specific that work to make biking safer and more comfortable.”

Having worked on bike projects for more than a decade, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Hanson himself is a regular cyclist, relying on his bike for most trips. He credits the local bike culture as a major contributing factor to what makes Minneapolis such a great place to bike. On any given week, there are dozens of social rides throughout the city, including non-drop rides, family-friendly outings, and meet-ups for identity-specific groups. There are organizations that empower people to be comfortable on their bikes through all four seasons, as well as Grease Rag and other groups that provide inclusive environments for bicycle education.

Hanson also credits local advocacy groups and community-based organizations with helping create a safer, more comfortable, and more equitable environment for bicycling.

“We've found a lot of value in partnering with established community groups and organizations to perform better, more meaningful project engagement,” says Hanson. “Doing so allows us as city staff to better build relationships with residents through trusted community members. Meaningful relationships are a really, really important resource for us.”

In recent years, Minneapolis has also been the site of racial unrest and the need to connect with and prioritize the needs of historically underserved communities has been pushed to the forefront. The city recently created a Racial Equity Framework for Transportation, which acknowledges that certain populations and geographies in the city have borne the brunt of displacement, pollution, and a slew of other outcomes directly tied to an inequitable transportation system. Importantly, this framework can help city planners be strategic and prioritize transportation investments in those same communities.

Hand in hand with those investments is a tangible plan for lowering barriers to bicycling through youth education. Currently, Minneapolis Public Schools are rolling out universal bike education for fourth and fifth graders in two-thirds of the city’s public schools, with plans for it to eventually be district-wide. After all, an all ages and abilities bike network only benefits youth that know how to ride.

“In the last few years, I think we’ve made some really meaningful progress,” says Hanson. “And I also appreciate that there’s always ongoing work to do.”

Kiran Herbert is the content manager for PeopleForBikes.