Build it and they will stay.

Cities can save themselves from the so-called “doom loop” by building more housing and investing in transit, according to a new report from longtime New York City planner and transportation analyst Bruce Schaller.

Schaller’s report parries the observable truths of hard hit urban cores seemingly in decline: transit ridership is down, housing costs remain prohibitive for many, and the pandemic drew upwardly mobile remote workers to heretofore un-commutable bedroom communities. Others, as Schaller noted, brought the weight of big city forces to smaller cities like Nashville and Orlando, underscoring his theory that American cities have always been and will always be motivated by the tension between the pull toward productive urban centers and the desire for more affordable, spacious space.

The meat of the report, though, lies in Schaller’s affirmation of transit and housing (the lifeblood of urban density itself) as tried and true vectors for sustainable urban development.

“The heart of the matter going forward is making more intensive use of land in and near the metropolitan center,” Schaller concluded. “That means denser housing, less reliance on the automobile, making urban centers safer and more conducive to traveling by foot and by bike, and enlarging the public realm. Rather than making city-building processes obsolete, the pandemic made them more important, and in more places.”

First, though, Schaller walks readers through the pandemic as experienced through the headlines on urbanism. Most Americans saw this in the pages of the real estate section. Connecticut home prices, for example, spiked about 25 percent during the pandemic as young and moneyed New Yorkers traded Dumbo for Darien. But it wasn’t just transitions out of legacy cities that captured the nation’s attention. Many of America’s opinion writers became armchair urbanists trying to make sense of the COVID exodus while toying with a Zoom-fueled “doom loop” for conventional city life. In October 2021, the New York Times even ran a 1961 review of Jane Jacobs’ “The Death and Life of Great American Cities.”

The pandemic changed things. But Schaller says that COVID ultimately showed the purpose, function, and spatial logic of American cities.

“We all feel the tension between the pull of a vibrant urban environment, in downtown central neighborhoods where there’s a lot to do, there’s a lot of activity, there’s a lot of people you can interact with,” said Schaller, an avowed Jacobs acolyte. “On the other hand, we feel the pull of open space and nature and a sort of greener and more relaxed environment that you find in the countryside.”

In his report, “Boom Times or Doom Loop? America’s Urban Future, Post-Pandemic,” Schaller roots his argument in what he calls the “inward/outward dynamic.” The report identifies the wealth and opportunity afforded by dense urban centers as inward forces. Consequently, the wealth and gridlock resulting from these urban centers tend to push people outward toward more spacious and less-expensive places. Essentially, Schaller concludes that cities generate material, cultural, and all other kinds of wealth, but the externalities push people toward the suburbs.

For Schaller, looking at cities through the lens of inward/outward tensions means understanding urbanism as an iterative process that the pandemic was able to rattle, but not break. Schaller dismisses critiques that telework permanently severed ties between where we live and where we work as a sort of pandemic aberration.

“There was a lot of logic to people leaving the city” during Covid, Schaller said. “There wasn’t anything going on in the city, and why put up with the expense? And why not get more space? You’re working at home. So there was this one-time shift in the amount of space that people want in their living quarters. That drove up housing prices all over.”

By all over, Schaller means that almost literally, as pandemic-induced migration brought urbanites to cheaper, smaller cities with many of the amenities found in Boston or Los Angeles, places Schaller calls “super-star cities.” This also exported the weight of inward/outward forces — i.e. the generative potential of dense urban centers and the resulting desire to escape them — well known to San Francisco and New York to Nashville and Orlando.

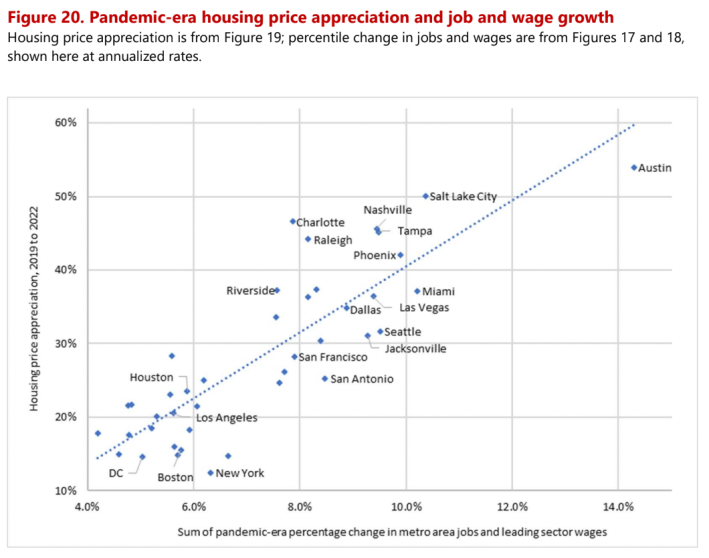

Schaller’s report explains this by diving deep into nearly 70 years of census data. By mapping the spatial and demographic profiles of 43 cities over time, Schaller shows the ebb, flow, and tentacles of American metropolises. In one of the report’s most telling figures, Schaller graphed the increase of housing prices from 2019-2022 versus the sum of pandemic-era change in metro area jobs and leading sector wages. Effectively, he mapped “the boom.”

Per Schaller’s analysis, leading sector wages in legacy cities like DC and Boston increased by around 5 percent versus a roughly 15-percent appreciation in housing prices. San Francisco, which is in all other ways generally the outlier when calculating land and labor statistics, fell near the middle with an 8-percent increase in wages versus a 30-percent increase in housing prices. Austin, Texas, with a more than a 14-percent increase in wages versus a more than 50-percent appreciation in real estate, practically broke the scale.

By mapping the boom, Schaller made an empirical argument for the fact that even pandemic urbanism generates a spatial relationship between wealth and demand for it. Austin’s off-the-charts numbers show that no city is immune to the pressures of “super-star” metros, and that cities across the country have to think critically about how to make growth equitable and sustainable through investments in housing and transit.

“The appeal of urban didn’t go away,” Schaller said. “And the central driver of the economy is needing that dense urban environment. … So the central point to the report is that this process of growth, development, urbanization, has now become pervasive. … Everybody is experiencing this process as there is growth in and near the metropolitan core. That is what is driving up housing prices is growth, for land is scarce and valuable. And everyone has to come to grips with what that means for how they grow.”

Migration, the rise of remote work, semi-occupied office buildings, lagging transit ridership, and low municipal tax revenues are all issues Schaller says that cities are facing, and by extension, fueling the debate over whether the next urban doom loop is already underway. Further complicating the post-pandemic city is the spate of issues that plagued pre-pandemic cities, perhaps most urgent among them, the housing crisis.

“The bottom line is that the inward pull, the centripetal pull, is still very much a key part of the dynamic here and people may opt for smaller metros, and some people may work remote, but it’s by no means the end of the big city,” Schaller said. “The big city still has all the advantages that come with in person interaction and exchange that it always did. But it has exacerbated the housing crisis. Because people want more space, wherever they are.”

Schaller’s parting words of caution: “For both the nation’s leading metros and for the country as a whole, the stakes of getting this right are enormous.”