More than 20 percent of car-free U.S. adults in car-dependent places are skipping medical appointments because they can't physically get to the doctor, compounding the challenge of accessing a broken health system that already too often puts care out of reach even for those with automobiles, a new study finds.

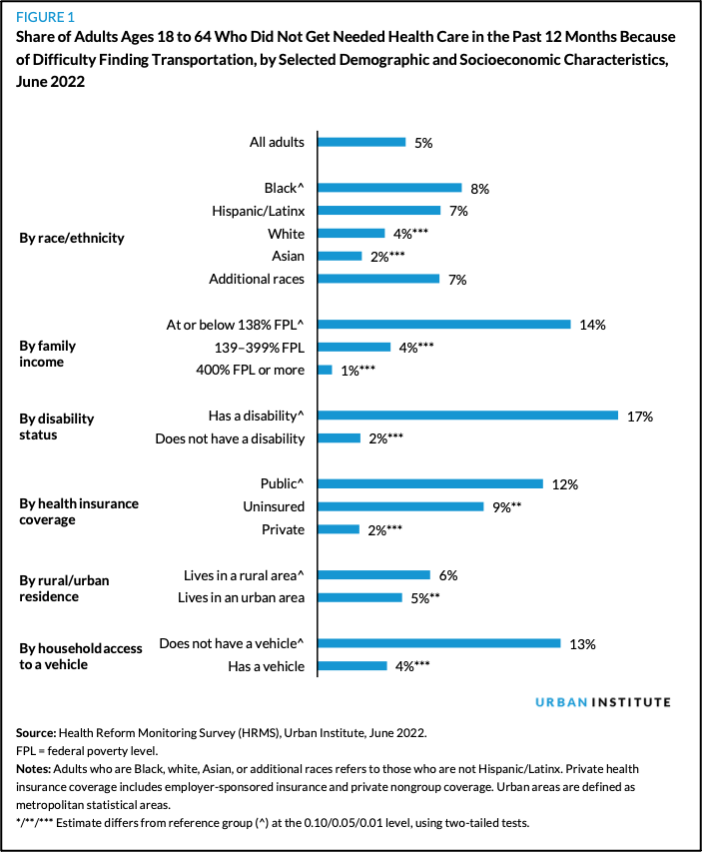

Researchers for the Urban Institute found that "because of difficulties finding transportation," roughly one in five non-elderly adults without access to a private vehicle or access to good transit were unable to obtain necessary healthcare at some point in the last 12 months. By contrast, only 5 percent of the general population said the same.

Others, including people with disabilities, low household incomes, and those who rely on public health insurance plans like Medicaid, as well as people of color and those who live in rural areas were likely to skip care because they couldn't get a ride — even if they didhave a car in the household, which those groups disproportionately didn't.

Of course, it's not exactly news that structurally racist, classist, and ableist planning policies have put critical destinations out of reach of vulnerable families across America, including grocery stores, jobs, schools, and so much more. DOTs generally aren't required to even measure how easy or difficult it will be for residents to access basic services across all modes as a result of new transportation investments — even though they are generally required to measure how those investments will impact vehicle delays for drivers.

But the researchers emphasize that gaining physical access to healthcare may pose its own unique, compounding challenges for underserved people, many of which have are woefully under-studied.

Urban Institute research associate Laura Barrie Smith pointed out, for instance, that because only 71 percent of hospitals accept Medicaid, recipients are often forced to travel longer distances to see providers they can afford — a problem that may be particularly acute in states that have made fewer people eligible for state-sponsored plans and disincentivized proximal hospitals from accepting public coverage.

A wave of hospital closures in rural areas, meanwhile, are increasingly making it even harder for people in the most transit-poor communities in the country to see a doctor for even routine medical reasons. And that's not even considering the fact that many disproportionately rural states have enacted or are poised to institute bans on specific forms of care disproportionately needed by low-income people, like abortion, or restrictions on gender-affirming treatment, which people with disabilities already struggle to access — both of which can force patients to either forgo life-saving care or travel hundreds of miles to reach it.

"We have such a complicated healthcare system that there’s never going to be a one-size-fits-all way to promote access to care," said Barrie Smith. "It’s really going to require people from outside healthcare to work together with policymakers and sustainable transportation advocates to address this."

The good news is that improved transit can make a huge difference in the lives of car-free Americans — if it's done right.

Among households without access to a vehicle, only nine percent of the people who reported their public transit access as "excellent, very good, or good" said they'd skipped the doctor for a transportation-related reason in the last year. People who simply lived near a transit line, meanwhile, weren't always more likely to get care, because proximity alone "may not capture the limitations people face as accurately as their subjective perception of public transportation accessibility," the researchers wrote. (Put another way: a train station on the corner may not do you any good if the train only comes once an hour, or if you can't afford the fare, or if you're terrified of being assaulted by transit police or murdered by another passenger onboard, or any of the other reasons why a marginalized person might not be able to make full use of their shared transportation network.)

Expanding telehealth options and non-emergency medical transportation benefits available under many health insurance plans could help, too, particularly if public transit fares are made eligible in addition to on-demand shuttles.