A popular European app that incentivizes users to walk instead of drive with cash rewards is coming to the U.S. — and the developers behind it are betting that it can get people moving on their legs even on dangerous American roads.

For the first time, stateside cell phone users can now download the popular WeWard app, which translates the number of steps they take each day into digital coins redeemable for real-world prizes such as discounts to major retailers, donation credits to charities, and even cold, hard cash. The app makes its money from corporations that advertise on the interface, rather than user fees, and, in some cases, local governments that believe the app can help reduce their public health costs.

The idea isn't new; app developers have been slapping ads on activity trackers and offering users a cut for a while now, and health insurance companies have long offered discounts on premiums to customers who use pedometers, too.

Much like those apps, WeWard is basically a dopamine-manipulation machine with a sidebar of sponsored content, inspiring users to earn their "Wards" not just by walking further than they did yesterday, but by completing computer-generated challenges ("Take 10,000 steps a day for 15 days straight!") or besting their friends in virtual competitions. There is, of course, an adorable cartoon panda to cheer you on, as well as a dashboard of metrics, though no data is shared with third parties without explicit permission.

WeWard may be unique, though, in its emphasis on replacing vehicle travel with walking trips, rather than just, say, getting dog walkers to take a couple extra laps around the block. The company is coming to America in part because it identified the U.S. as "one of the most car-centric countries in the world," and advertises its past success not just in terms of heart-healthy miles traveled, but in terms of carbon reduction thanks to avoided automobile trips.

A study commissioned by the company claims that WeWard users reduced their collective carbon emissions by 588,000 tons in the last 12 months, roughly equivalent to the annual carbon output of 126,696 gasoline-powered vehicles (at least under the EU's slightly stricter emissions standards). In France, where the app was launched in 2019, a full 10 percent of citizens use it, and its 10 million worldwide members have reportedly increased their daily steps an average of 24 percent since downloading it to their phones.

Those environmental and health benefits, the app developers emphasize, are accompanied by harder-to-measure social benefits for society, too.

"Almost all the technology that we've created has helped us to become less active," said Yves Benchimol, WeWard's co-founder and CEO. "You can order your food directly to your door; you can order an Uber that will pick you up and take you to a restaurant; you can work from your couch on Zoom. You can interact with people, yes, but you can’t really be together in community with people. But we think we can also use technology to do the opposite."

Benchimol makes the bold (and, to be clear, completely unverifiable) claim that "compared to almost all health policies developed by government, WeWard may be more effective" at transforming people into frequent pedestrians. He acknowledges, though, that the app will face new challenges in a country like the U.S., where residents travel roughly double the number of annual miles in a private car as their French counterparts, particularly because the app's incentives are fairly small: he says the average WeWard user makes about 100 Euros off the app.

"We believe the benefits of more walking will be much more intense in the U.S., because right now, so many basically don't walk at all," he said. "[An app like WeWard] doesn't give you a big incentive, but it’s enough to stimulate your brain and give you a shot of dopamine. Even just a little bit is like magic."

Whether that magic can work on Americans in car-dependent city, though, remains to be seen.

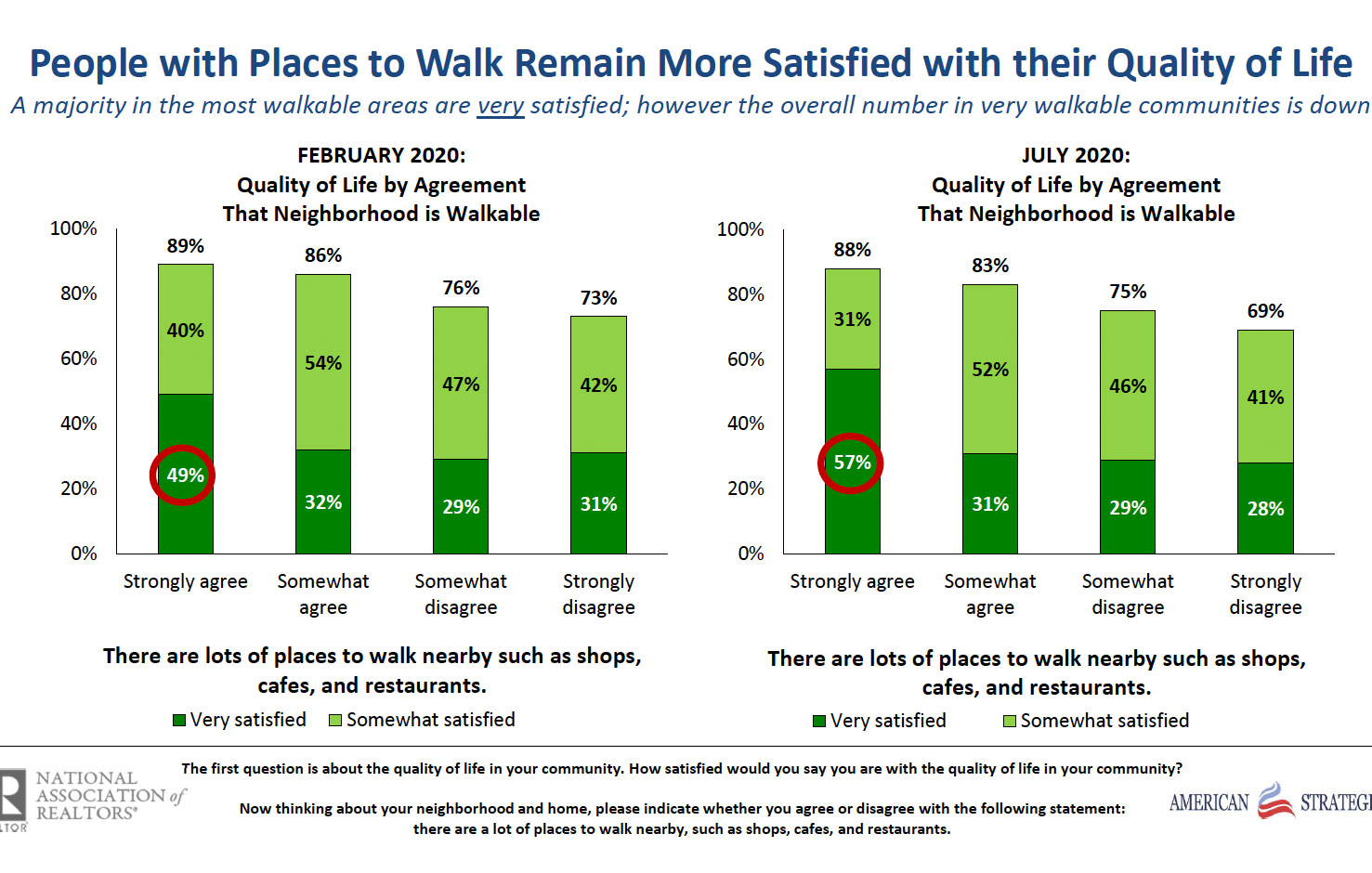

The sad fact of the matter is, only about one in 12 U.S. residents lives in a neighborhood with a WalkScore of at least 70, indicating that they can accomplish most of their daily errands on foot — and since WalkScore itself tends to overestimate a neighborhood's actual walkability, the number may actually be lower.

Suffice it to say, getting the other 11 Americans moving on their own power will probably take a lot more than a cute panda and the tantalizing promise of a coupon at the Gap. It will take building sidewalks near their homes where there are none, and slowing cars to non-lethal speeds, and remaking decades of bad zoning that has placed the nearest grocery store more than two miles from the average American household. And that's to say nothing of the unique and often profound barriers faced by people from marginalized groups, like fear of police harassment among people of color, fear of sexual harassment among women and queer people, and so much more. (It should also be noted that WeWard does not offer an step-equivalent option for people in wheelchairs or forgo car travel.)

In order to earn enough coins from WeWards to get a $70 bank transfer — the app's top prize — the average American would need to walk at least 10,000 steps a day for 1,000 consecutive days, more than twice the 3,000 to 4,000 daily steps she logs now.

Still, Benchimol is optimistic about WeWard's potential to get Americans walking — or at least, to get them talking about why walking matters.

"When we talk about sustainable transportation, people think about cycling, electric cars, transit, but they don’t talk so much about walking," he added. "We think we need to make walking the center of the debate."