Downtown rush hour has still not roared back to pre-pandemic levels even as car travel surges in the suburbs, a new study finds — and it may help explain why traffic deaths have stayed so stubbornly high in U.S. communities.

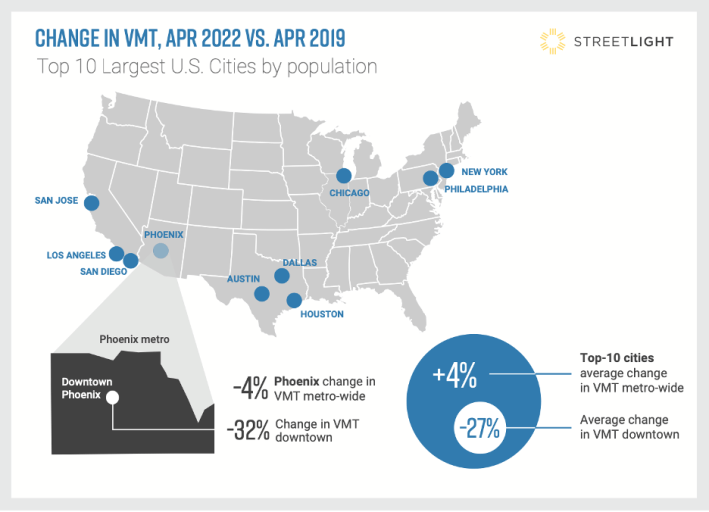

According to the transportation analytics firm Streetlight, the number of motorists driving through America's 10 largest city cores in April 2022 was down a whopping 27 percent compared to the same month in 2019 — with some particularly car-dependent areas, like downtown Phoenix, experiencing as much as a 32-percent decline.

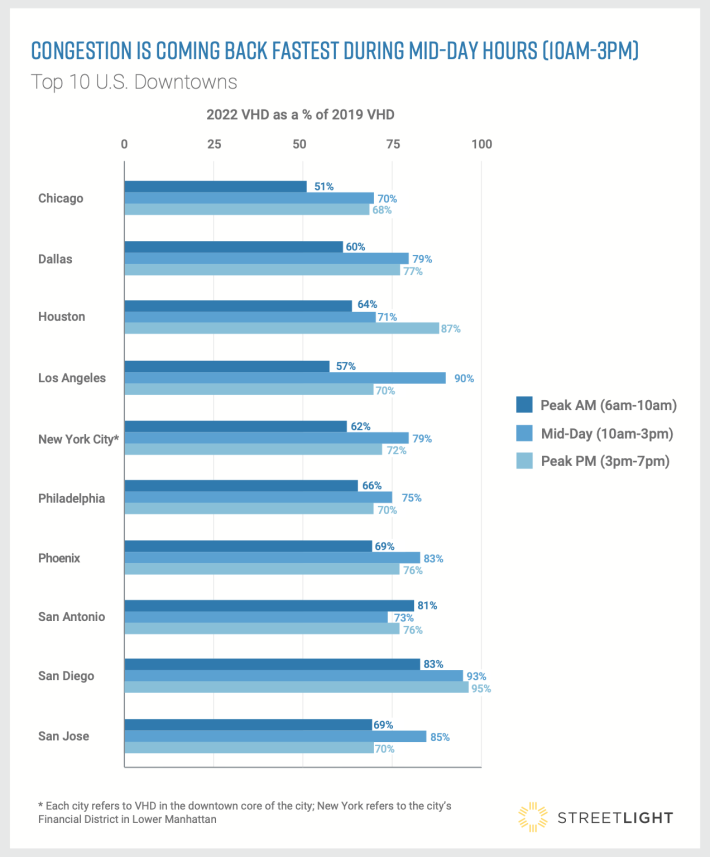

And those drops weren't distributed evenly throughout the day, either. During what used to be the peak morning rush hour, average "vehicle hours of delay" were down a staggering 40 percent compared to before the pandemic. At midday, they were down just 22 percent — and given high rates of vacancy in downtown office buildings, the researchers theorize that the rise of remote work is why.

"Historically, these areas have depended a lot on the daily office population, even in supposed 24-hour cities like New York and San Francisco," said Martin Morzynski, a spokesperson for the company. "Even now, there are hundreds of thousands of people missing from American downtowns — and they're predominantly white-collar workers who used to work in offices and now work from home."

At first, fewer drivers in places where people are most likely to walk might seem like a win for traffic safety. But as countless American communities learned all too well during the Covid-19 quarantines, an absence of traffic jams without accompanying infrastructure changes to slow down the drivers who remain can transform whole communities into wide-open raceways — and send road deaths skyrocketing, particularly among vulnerable road users.

Pedestrian deaths spiked 21 percent between 2019 and 2020, despite — or, more accurately, because — of the near-total absence of congestion as U.S. residents sheltered in place.

Experts have struggled, though, to explain why deaths kept going up in 2021, even as national vehicle miles traveled climbed closer towards pre-pandemic averages. Streetlight's data may lend credence to one popular theory: that now-remote workers are spreading their mileage more evenly throughout the day and across a wider variety of non-downtown roadways, enabling them to avoid traffic jams and maintain deadly speeds almost everywhere they go.

"A lot of these workers are driving as much as ever, but they're not always commuting downtown anymore," Morzynski adds. "They may be getting out and driving to coffee in their suburban neighborhood than walking to the coffeeshop down the street from their office; they might be picking up the kid from school rather than having them take the bus; they’re running a midday errand that they otherwise would have bundled with another trip."

Morzynski is careful to note that changing traffic patterns probably can't explain all of the pandemic's traffic death trends, and that reckless driving, dangerous vehicle design, and people walking more on pedestrian-hostile roads are probably playing a role, too. Still, he says the safety impacts of the shift deserve further study — not just in city centers.

"We do data to back up that, despite traffic being down on average in the urban core, there are certain roads — highways and highway-feeders in the suburbs— where there are a lot more cars than there were before," he adds. "What that means for safety is that, if you’re a cyclist on one of those roads, well, things might be a little more dangerous and dicey than they were before."

Rather than attempting to woo automobile commuters back downtown, the Streetlight researchers say the pandemic has offered officials "a chance to return many public spaces to pedestrians and cyclists" and allow city cores to go back "to their roots as mixed-use communities with denser urban amenities like restaurants, cultural venues, schools, and other services."

Morzynski adds that some local governments got a taste of that when they piloted open streets events and other initiatives during quarantine — and he's hopeful that many are contemplating more permanent change.

"What we're hearing a lot more from cities since the pandemic feels like a culture shift," he said. "[Leaders are saying], 'While we care about congestion, we care more about safety — and if we have to slow down cars to make people safer, that’s okay.'"