America's mid-century freeway revolts never really stopped — and now, the advocates behind them are joining forces to create what may be the largest organized national effort to prioritize communities over highways yet.

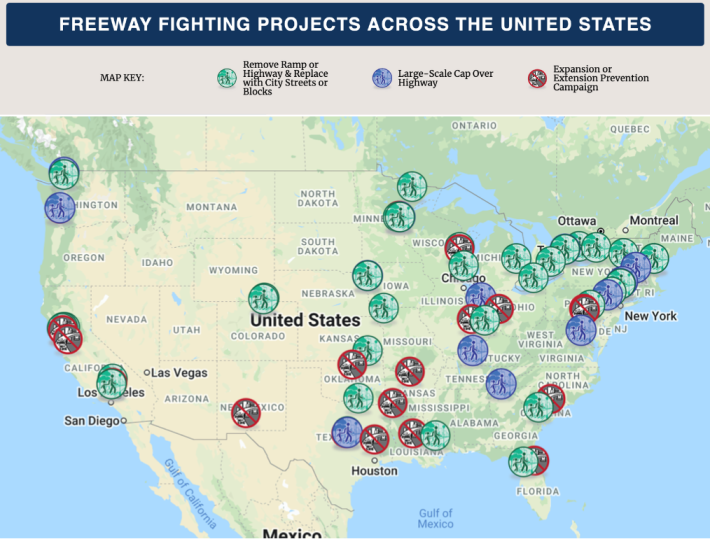

On Tuesday, the Congress for the New Urbanism formally launched the Freeway Fighters Network, a national coalition that brings together activists and allies from across the country who are fighting to keep high-speed road expansions out of their neighborhoods, tear down the highways they've already got, and heal the scars that autocentric infrastructure leaves behind — particularly in communities of color.

And those advocates are doing more than just cheering each other on. The site aims to be an organizing hub not just for the 35 distinct anti-highway campaigns and counting that are already on the site, but for national efforts to reform to auto-focused federal policy more broadly, as well as an informal clearinghouse of studies, advocacy strategies, inspiration for action.

Perhaps most critically, though, the Freeway Fighters Network offers a rare opportunity for far-flung advocates to talk shop and find new strategies. Since the coalition soft-launched last year, more than 230 activists and allies have already joined a sprawling conversation on the group's Discord chatrooms and list serv, and far more are expected to join the conversation now that the effort has gone public; advocates against four separate highway projects in Texas have already began organizing a unified front against the state DOT, thanks in part to the connections they made on the site.

"These are groups are sharing best practices, they’re showing up to each other’s fights, and it’s often providing a bit of group therapy," said Ben Crowther, program manager for the Congress for the New Urbanism. "Organizing against freeways can be isolating, and these communities are going up against large agencies that dwarf them. It’s really amazing to see them come together and build power."

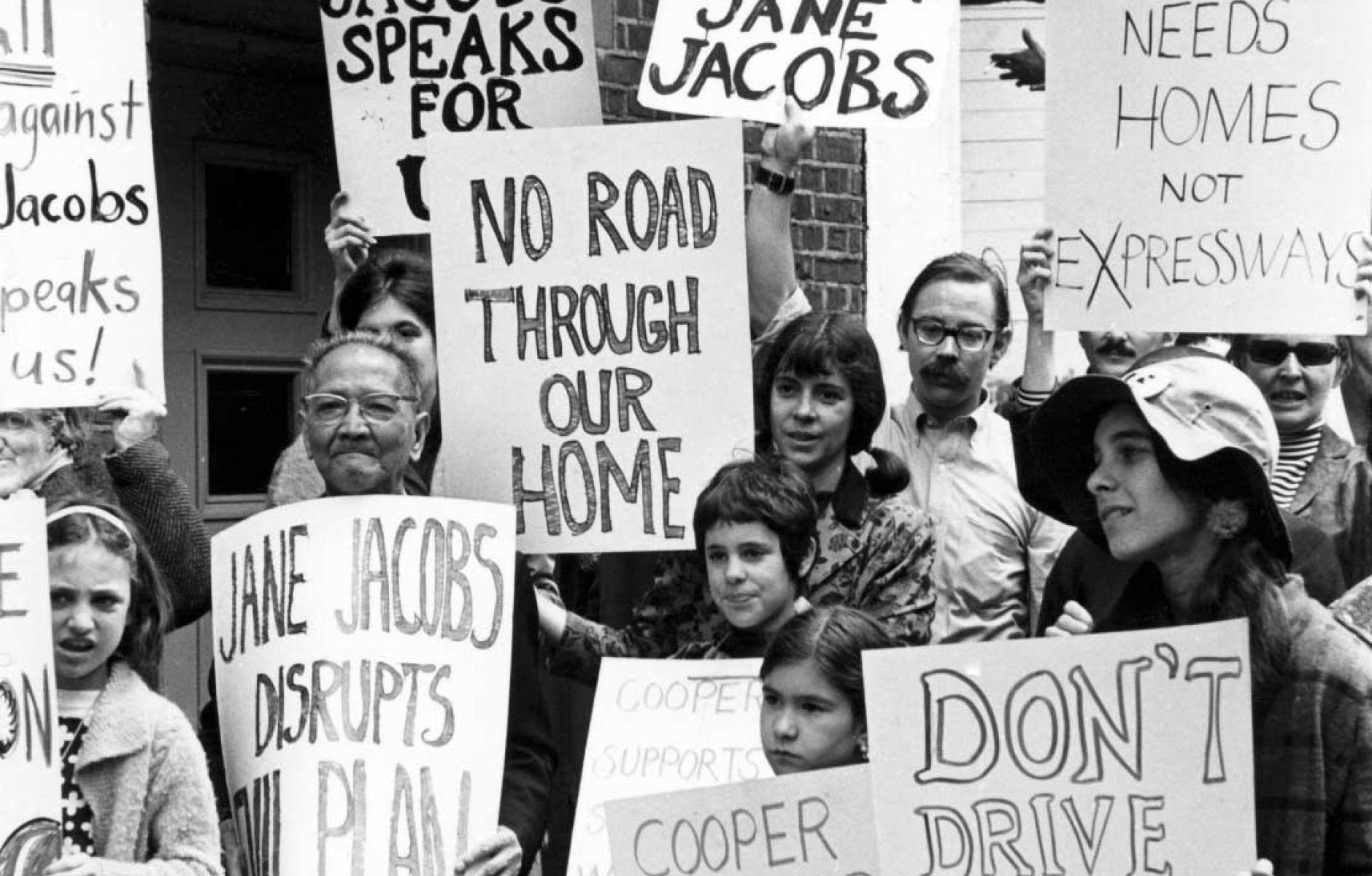

In many ways, the Network draws inspiration from the roughly 123 anti-highway efforts that sprung up across America when the interstate system was first built in the 1950s and '60s — a tally that even includes a few famous success stories, like the defeat of the Lower Manhattan Expressway that helped catapult proto-freeway-fighter and author Jane Jacobs to urbanist stardom.

Many of those local protests ultimately failed, but the advocates behind them kept fighting, organizing over the phone and even the mail to win federal protections for future communities. Now, as the highways rapidly approach the end of their lives, those policies are poised to take full effect — especially as anti-freeway advocates find each other online and build collective power.

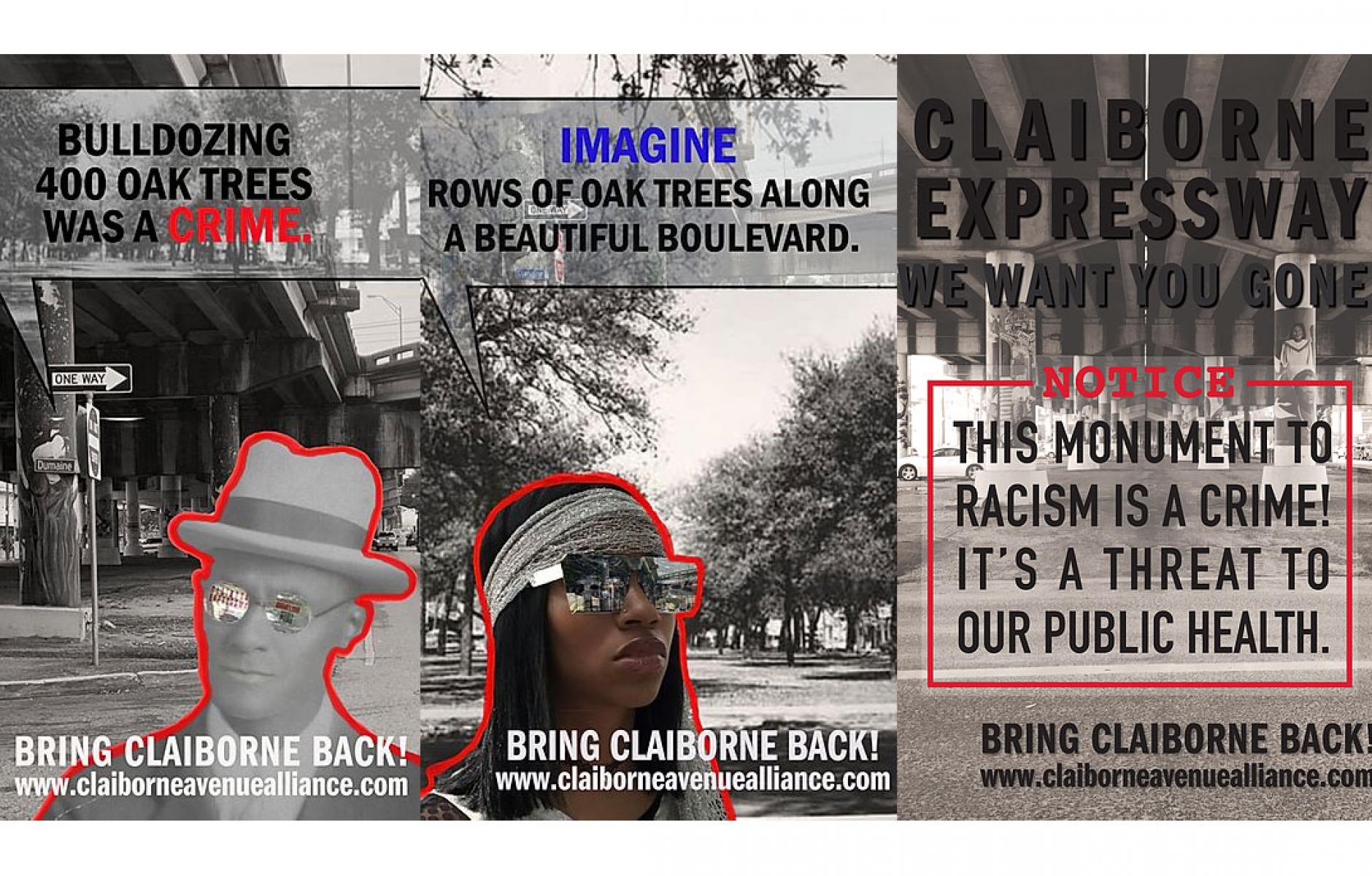

"I’ve never liked 'the monster' — that's what our community calls the highway — and I vowed as a kid that when I was old enough to change it, I would," said Amy Stelly, a multidisciplinary artist and urban designer from New Orleans, La. "What I realize now is that even if I had started back then, I wouldn’t have been as effective as I am now...Timing is everything."

Stelly's "monster" is the infamous Claiborne Avenue Expressway, an elevated portion of Interstate 10 that has cast a devastating shadow over the historically Black Tremé neighborhood for more than five decades. President Joe Biden publicly cited the project as a prime example of the racist urban renewal policies for which U.S. DOT must atone, though the funds he hoped would help the agency do that were whittled down from $20 billion to just $1 billion during negotiations over the latest infrastructure package.

Stelly hopes that the Freeway Fighters Network will help build support for expanding that pot of money — and give each other tips on how to recruit more allies to the fight.

"The best resource that we have is one another," Stelly added. "But it's not just about sharing experiences and stories. In my experience, tapping into the brain trust of the community is the way to get to more of the hardware – the money, the funding, the support of institutions."

Like all freeway fights, Stelly's quest to quell the Claiborne monster is unique, and the messaging that she's found most effective with her neighbors is unique, too. But she and her fellow freeway-fighters stress that their campaigns have more in common than they don't.

"You want every freeway movement to use different language that resonates with local leadership," said Aaron Brown, an organizer with the Portland-based nonprofit No More Freeways. "But we all have this fundamental problem that state DOTs have too much power over decisions that have a huge impact on local communities. In pretty much all of America, the normative assumption is that the state has the right to obliterate a city if it can make commutes shorter for exurban residents — at leasts for a short while, until it’s filled up with cars again."

Brown has been active in the fight against the Rose Quarter expansion project, which threatens to roughly double the width of a major Portland highway that runs astride one of the region's few predominantly Black middle schools. He says the Network is helping him not just find the strategies and co-conspirators that will help them win — Stelly recently spoke at a conference he helped organize — but to have a meaningful conversation about what comes after.

"Freeway expansion is, in my view, the cardinal sin of modern planning," Brown added. "If we’re serious about providing reparations to communities of color, we need to say, 'we fucked up.' We need to tear them out and give [resources and land] back to the Black and brown people whose intergenerational wealth we plundered."

And in the meantime, he hopes the platform helps philanthropists for climate and racial justice discover a cohesive, national movement that needs their support.

Until that happens, though, at least the advocates are finding each other.

"Fighting freeways feels very alienating, because you’re up against such a well-funded powerful exorbitant machine," he said. "The sappy answer, I guess, is just knowing we’re not alone."