A first-of-its-kind municipal law now requires many employers in Washington, D.C. to provide cash to workers who turn down their company-sponsored parking benefits — and experts say it could serve as a model for other American cities that want to de-incentivize car commuting.

After more than a year stuck in regulatory limbo, local leaders in the nation's capital are finally enforcing the Transportation Benefits Equity Act of 2020, which requires "that employers ... offer a 'Clean Air Transportation Fringe Benefit' in an amount equal to or more than the market value of the parking benefit" for employees who turn down the company-provided space.

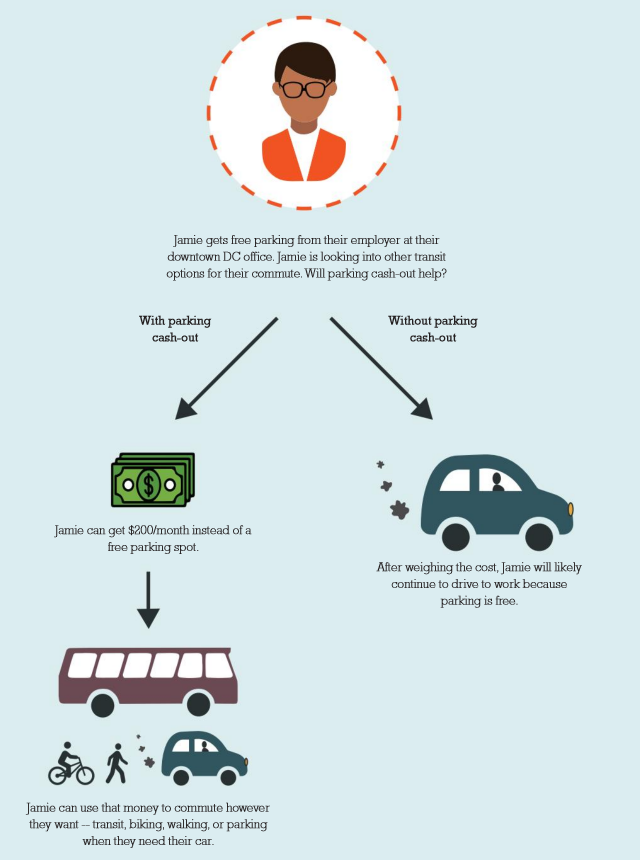

The new requirement is based on parking expert Donald Shoup's innovative "parking cash-out" model, which studies have shown is an effective tool to disincentivize car use. (Free parking, of course, has long been proven to encourage vehicle commuting.) Similar laws have passed at a statewide scale in California and Rhode Island, but neither applies to workplaces with fewer than 50 employees, and both offer generous exemptions for employers located in regions that already have good air quality, or that don't have strong transit networks that workers could realistically use instead of driving.

And critically, the California law only pays workers the amount their employer saves by not having to provide them with a parking space, not what that space is actually worth — which can mean a lot less money if the boss is getting a good deal on a contract with a private parking company.

The D.C. law, by contrast, will apply to virtually every employer in the District with 20 or more employees — a category which includes the vast majority of workplaces — and will require them to pay out the full market value of each spot, or follow other compliance paths aimed at decreasing regional driving mode share in other ways.

"It's a big deal," said Allen Greenberg, a D.C.-based parking reform advocate who wrote a thorough analysis of new law. "In the age of concern about climate and overuse of our streets and the danger of too many motor vehicles, it’s absolutely insane that we provide incentives to people to drive more."

#ParkingCashout: "The 1997 study found that after employers offered the cash option, solo driving to work fell 17%, carpooling increased 64%, transit ridership increased 50%, and walking or biking increased 39%." https://t.co/GPS2ciZNt9 via @citylab

— Gladwyn d'Souza (@godsouza) January 4, 2022

Washington's new law isn't perfect. In addition to exempting small businesses, the new rule won't apply to companies that own their parking lots rather than leasing them — a big carveout that Greenberg hopes other cities won't mimic.

"There really is no good policy argument for a blanket 'owned parking' exemption," Greenberg writes."Employers that own their own parking typically retain very substantial control over [that asset], including [the right] to sublet it to recapture the market value of parking that their employees 'cash-out' of."

And due to a quirk in the federal tax code, only employees who spend money on their commute — think transit passes, bike maintenance, and private shuttle service memberships — will benefit from the new law, meaning that workers who walk or catch a free ride with a coworker won't get anything. Those commuters can still qualify for a cash-out if they take an eligible mode at least once a month, but the workaround is inelegant, and advocates worry that some walkers will miss out.

At least initially, not every stakeholder was so sure that walking benefits should be a priority for the new D.C. law. Greenberg says that during the lengthy debate over the bill's details, some worried the cash-out scheme would largely benefit wealthy residents who can afford to live in pricey apartments within strolling distance of downtown offices, rather than low-income essential workers with lengthier commutes that often require that car. (In D.C., the highest walk-to-work rates before COVID-19 were found in relatively wealthy and overwhelmingly White Ward 2, where the median annual household income is over $112,000, with White residents enjoying significantly higher incomes than their BIPOC neighbors.)

Greenberg hears the concern, but emphasizes that only half of low-income households in D.C. even have access to a private vehicle — and those who qualify for subsidized bus passes stand to net some of the biggest payouts of all. Moreover, the new policy will encourage workers who do drive to stop clogging up the roads, making transit riders' commutes a little faster.

"Without transportation benefits equity, employers are [essentially] 'paying' car drivers with free parking — some of whom might otherwise not drive — to block the bus, while not compensating bus riders for their delay," Greenberg wrote.

Moreover, the climate, safety and quality of life benefits of getting a few more car commuters off the road will benefit the entire D.C. community — and other cities, too, if they follow the District's lead and adopt parking cash-outlaws of their own.

"We all pay the price as a society when employers bribe their employees to drive to work," Greenberg added. "There’s no good reason that if someone is given a parking spot, a parking cash-out shouldn’t be required [for their coworkers who don't drive], or that the employer shouldn’t have to meet goals to reduce single-occupancy vehicle commuting...Now that D.C. has done it, other cities won’t have to go through as much to get cash-out laws on the books."