An international nonprofit has developed a calculator to help Colorado residents quantify how adding highway miles in their state will translate into more cars on the road, and they’re hoping advocates in other states will follow suit.

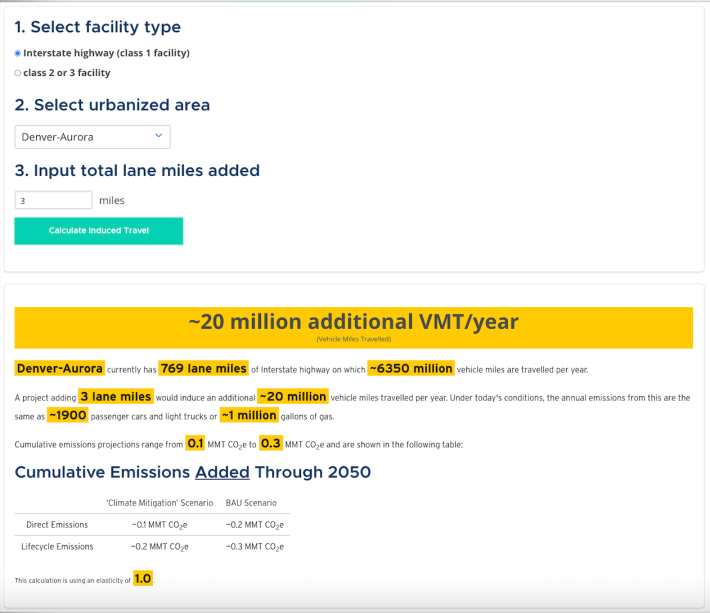

According to an analysis from RMI (formerly known as the Rocky Mountain Institute), the next 10 years of planned highway-expansion projects in the Centennial State could add more than 70,000 cars and as much as 1.5 million vehicle miles to roads each year. Even if only a few projects go forward, the surge in driving will be huge — a fact that Coloradans can see for themselves by plugging in the mileage and facility type for a proposed project into the team’s interactive calculator.

The findings may seem surprising for a state that has committed to reducing vehicle miles travelled by 10 percent by 2030. Just half a dozen states have set such a goal as part of their greenhouse-gas-reduction strategy, even though the RMI team found that the U.S. can’t meet its goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius without cutting VMTs by 20 percent and transitioning 70 million gas-powered cars to electric vehicles by 2030.

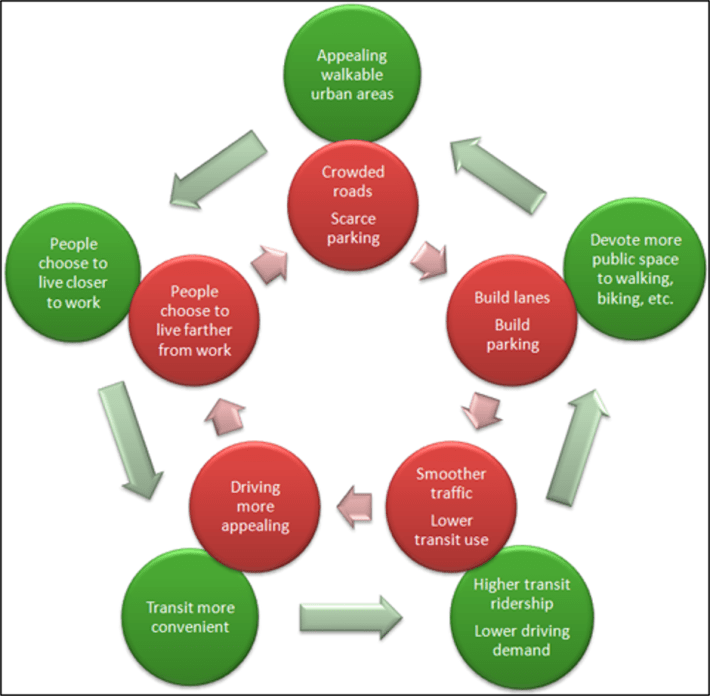

Of course, Colorado isn’t the only state that’s paying lip service to big transportation goals while rolling out the asphalt carpet for drivers — and that's by design. Most traffic models used by state and federal agencies in advance of new projects don’t adequately account for "induced travel" — when a community builds a highway in order to relieve congestion, but the road instead encourages drivers to travel longer, farther, and more often, leaving cities more car-clogged than ever.

Study after study has showed that a 1 percent increase in lane mileage results in about the same increase in vehicle miles travelled in a few years. But because the federal government funds highway expansion more robustly than just about anything else, state and local DOTs have little incentive to adjust their traffic projections to account for induced travel, much less kill projects that will bring more cars.

“When [departments of transportation] project for induced demand in their traffic models, they underestimate it by a factor of five to 10,” said Zack Subin, senior associate at RMI’s U.S. program. “We wouldn’t quibble if it was a small difference, but it’s huge. When the conventional process is this insufficient, it bears some attention.”

The RMI team isn’t the first to develop such a tool; University of California-Davis researchers used a similar methodology for a calculator for the Golden State. State highway director Shoshana Lew initially cast doubt on the model, saying that it omitted “a broad range of other factors pertinent to traffic modeling that affect vehicle miles traveled, mitigations, and the geographic nuances of individual projects,” but the team stressed that its methodology has been vetted by experts.

The RMI team is hoping that when state leaders actually take a look, they will start considering broader strategies to cut congestion, cure climate change, and meet the state’s VMT-reduction goals — without giving in to the seductive fantasy that stopping climate change will only require electrifying cars.

“As my colleague Zack likes to say, Almost all of the analytical firepower associated with transportation climate strategy has been devoted to getting people into electric vehicles,” said Ben Holland, senior association for RMI’s urban transformation program. “Understanding the impacts of highway expansion is just one piece of a whole puzzle, but when we [stop doing those projects,] it clears the way to talk about how land use, transit investment, zoning reform — how all these other things can help achieve our climate goals.”

Of course, the RMI calculator alone won’t precipitate that critical conversation. Equipping advocates with simple tools to quantify the effects of bad highway projects is one thing; requiring transportation leaders to do the same before they break ground on a boondoggle, as California did just last summer, would mean more.

Holland says that quantifying the positive effects of VMT-reducing projects could be an even bigger win — but data remains scarce.

“What policymakers really need is a defensible argument for including all these effective non-EV-related transportation strategies into climate transportation plans,” Holland said. “To date, they haven’t really had that, so people have defaulted to, ‘well, by 2035 all vehicles sold will be electric.’ It’s an area that’s under explored, and we’re really eager to put some real numbers to what we can do for the environment with things like zoning reform.”

Meanwhile, the RMI team hopes its tool will at least give Colorado advocates more ammunition to push back against highway expansions — and that advocates around the country will have similar tools soon.

“There’s been a ton of enthusiasm for replicating this calculator for other states,” Holland said. “We may be working on it ourselves, soon, but we certainly don’t want to stop anyone else.”