Almost all the climate and congestion benefits of online shopping are wiped out by rush deliveries, a study finds — which could spell disaster for U.S. roadways this holiday season.

Analysts from the University of California Davis ITS Institute for Transportation Research modeled how the rising popularity of same-day delivery might translate to delivery trucks on our roads and greenhouse gasses in our skies. Unsurprisingly, the faster a company races to deliver a package, the more likely it is to send inefficient, near-empty trucks to far-flung homes.

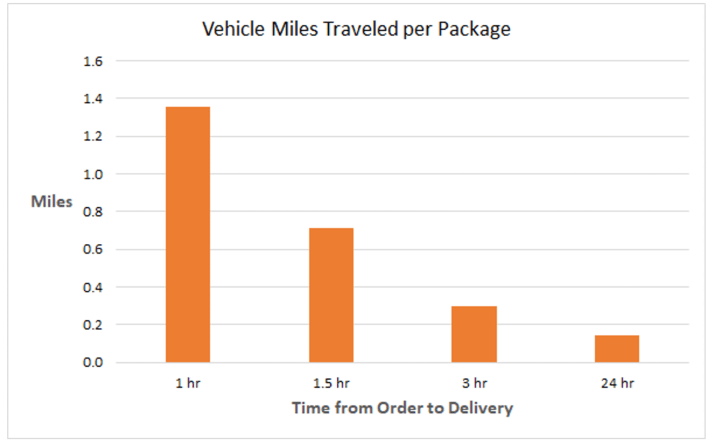

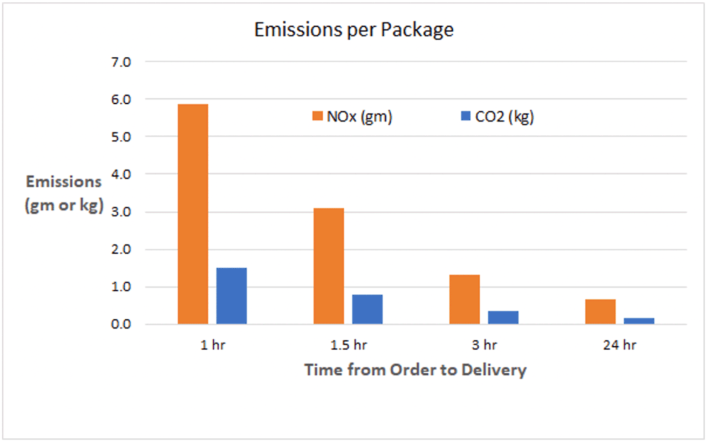

But just how much worse are those rapid deliveries are for the planet and congestion? The average vehicle miles travelled for a package that was delivered in an hour or less was seven times higher than for a package delivered in as little as 24 hours; per-package nitrogen oxide emissions, meanwhile, were about six times higher for customers who selected the fastest available shipping.

And that's before accounting for the VMT and climate effects of customers returning their packages, which happens to some 15 to 40 percent of items purchased online. (The next time you buy a sweater on the web, remember: Apparel is by far the worst online retail sector for our roads.)

The findings shine light on the effect of online shopping on our cities, which transportation researchers have long struggled to grasp — and local leaders have made almost no efforts to regulate, despite mounting evidence that rush delivery are contributing to traffic violence, congestion, and climate change.

Part of the reason why is corporate secrecy. E-commerce giants such as Amazon are notoriously silent about how many trucks they send into U.S. neighborhoods every year, although they also boast about how much they lose on rush shipping doesn't matter to them one bit.

Still, the proof is piling up. A 2019 Propublica investigation found that Amazon drivers had been involved in at least 60 car crashes across the country since 2015, a tally that experts concluded was likely only a fraction of the collisions that had occurred, because "many people don’t sue, and those who do can’t always tell when Amazon is involved" because of the company's reliance of independent contractors as drivers.

The same year, a New York Times investigation disclosed that the average number of daily deliveries to homes in New York City had tripled from 2009 to 2017. Trucks tasked with delivering more than 1.1 million shipments every day had clogged streets so badly that experts say rush delivery alone accounted for a staggering 23 percent rise in travel times in the busiest parts of Manhattan.

But the full picture of the e-retail revolution's effects on our roads has been clouded for another reason, too: the evolving logistics of getting billions of packages to American doorsteps itself, which gives corporations a smokescreen for bad behavior.

Put simply: if companies such as Amazon were subject to traditional laws of economic gravity, free, same-day shipping probably wouldn't exist. The costs of complex warehousing schemes, split orders, and returns would have crippled even the biggest online retail giant long ago — if we didn't live in an economy that treats short-term losses as a sensible price to pay for total retail domination, not to mention a political climate in which deadly, congested roads are seen as a sign of economic health rather than a crisis. (Amazon's plans to electrify its delivery fleet are admirable, but that alone won't do anything to make our roads less congested and dangerous or to make our world less car-dependent.)

A slower, more local kind of online retail, on the other hand, could reduce vehicle miles travelled — if we did it right.

In their review of the available literature, the UC Davis researchers noted a study that showed that, if half of city residents used a grocery-delivery service (preferably one with strong worker protections), it would reduce VMT by up to 20 percent — which countless communities later saw demonstrated in the early days of the COVID-19 lockdowns. If smaller companies committed to finding the right mix of in-neighborhood fulfillment centers, e-cargo bikes for last-mile delivery, and a few other logistical improvements, those effects could extend to other sectors, too.

But shrinking the congestion caused by the e-commerce giants probably won't be so simple. The UC Davis researchers pointed out that many studies hailing e-retail as a panacea for VMT reduction "assume 100 percent penetration of e-commerce ... an assumption that might exaggerate the potential of e-commerce to cut congestion and emissions."

But therein lies the problem — because the closer we get to fully online retail, the closer we get to a dystopia in which neighborhood shops and groceries are eliminated in favor of windowless warehouses. That's a world in which few would likely want to live — even though, during the pandemic, we sort of are.