The pandemic has made car addiction three times worse.

Drivers are valuing their access to a private vehicle during the pandemic more than three times as much as they did before COVID-19 — but they can be persuaded to get around without a car with simple changes to incentivize other modes, a new study finds.

To understand why some Americans still choose to pay to maintain a private vehicle even when robust public transportation networks are right outside their door, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology surveyed around 1,000 people each in the transit-rich cities of Washington, Chicago, and Seattle. (They also spoke with 1,000 people in mostly-car-dominated Dallas, though for the record, its light rail system boasts surprisingly high ridership.) Then the researchers offered the subjects a series of hypothetical cash bribes in randomized amounts to give up their cars for up to a year — and also asked them whether they'd take the same deal if they'd been offered those incentives prior to the pandemic.

And the offers weren't limited to cold, hard cash alone. Later in the survey, the researchers tempted respondents with access to a "free, ubiquitously available ride-hailing service" in exchange for giving up their private vehicles — essentially, a gratis private car service that might sometimes require a very brief wait.

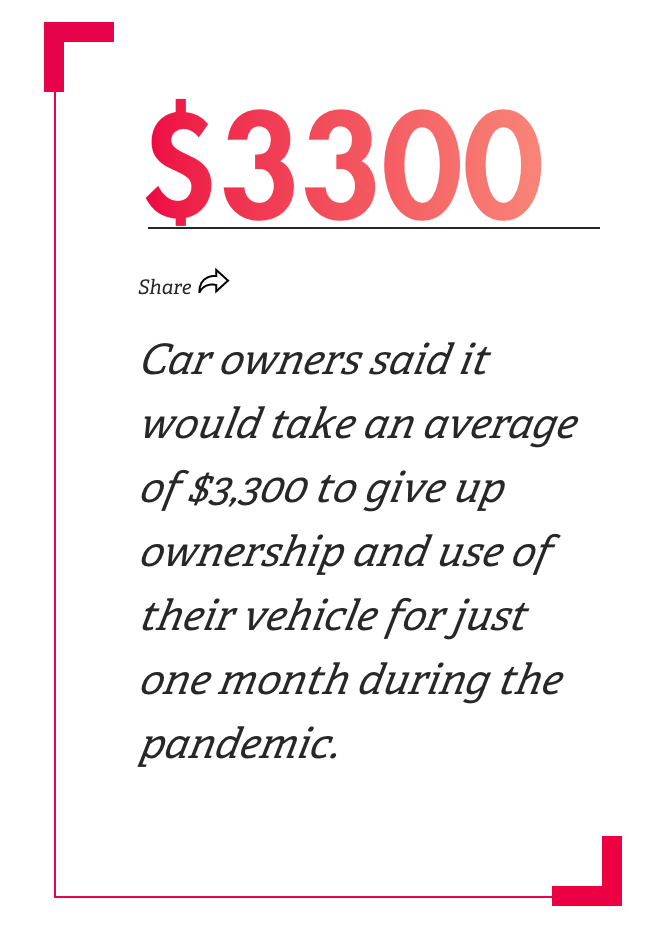

What the researchers found was astonishing: Even prior to the pandemic, drivers said they'd need a whopping $11,200 on average to entice them to give up immediate, 24/7 access to their personal cars. Even if they had a free, high-quality e-taxi at their beck and call, the respondents said they’d need around $6,500 in compensation to give up their car ownership. And during COVID-19, they said they'd need $3,300 every single month — that's $39,600 over the course of 12 months — just to say goodbye to an object that already costs the average U.S. drivers $9,300 a year just to finance, fuel, insure, store, and maintain.

Put another way: we've created a society that's so paralyzingly car-dependent (and so convinced of the myth of COVID-19 risks on public transit, not to mention taxis and other modes) that the average American earning the median income of $68,703 would need a cash payout of the equivalent of 71 percent of her total annual pay in order to even consider giving up a private vehicle during a year-long pandemic.

And even without a virus, that same would-be car-free commuter would still ask for a cash payout equivalent to the cost of an average year's worth of groceries, health insurance, and electric bills, plus a round trip flight to Paris.

How 'option value' helps decode the psychology of American car dependence

The finding is a fascinating example of how human behavior is shaped by the power of "option value" — a wonky economics term that refers to the dollar value that people place on having the option to use a good or service if they chose to do so, as distinct from the money someone will pay to actually use that thing.

The term is usually applied to stuff like a resident's willingness to pay a tax to maintain a local park he or she might only visit once in a blue moon, but "option value" is a powerful and under-examined feature of consumer psychology, too. And it definitely helps explain drivers' willingness to spend an average of 9.2 percent of their household income on a hunk of metal that sits parked 95 percent of the time — and why, during the age of mass quarantines, work from home, and historically low vehicle miles travelled, they value their wheels even more.

"When we isolated how much drivers valued car ownership on its own, [independent of the value they placed on actually being able to drive that car], we found that it was about $6,500 in a typical year before the pandemic," said Joanna Moody, research program manager for MIT's Mobility Systems Center and one of the authors on the study. "That means only 58 percent of the perceived value of car ownership actually comes from ownership itself — not use."

So if drivers don't value their cars simply because they're useful — and often, outright necessary — to navigate our auto-dependent cities, why do they insist on pouring money down the gas tank, even if they live in a transit-rich city like D.C.? Moody says that option value as well as intangible factors like social status, privacy, and emotional and symbolic connections to car ownership all play a role — and right now, the terrifying uncertainty of the pandemic is a major factor, too.

"Car ownership is a security blanket," Moody says. "The more risk-averse we are, and the more unpredictable our travel needs are, the more attractive the flexibility, reliability, and control that comes with car ownership becomes. Especially right now, people are asking themselves: what if I need to get to the hospital at a moment's notice? What if transit service is cut because of the pandemic and I can't make it to work? It’s really about having the option of being able to take the car when they might need it that's so important to people — even if they don't actually do it much at all."

How to lower the value of easy driving

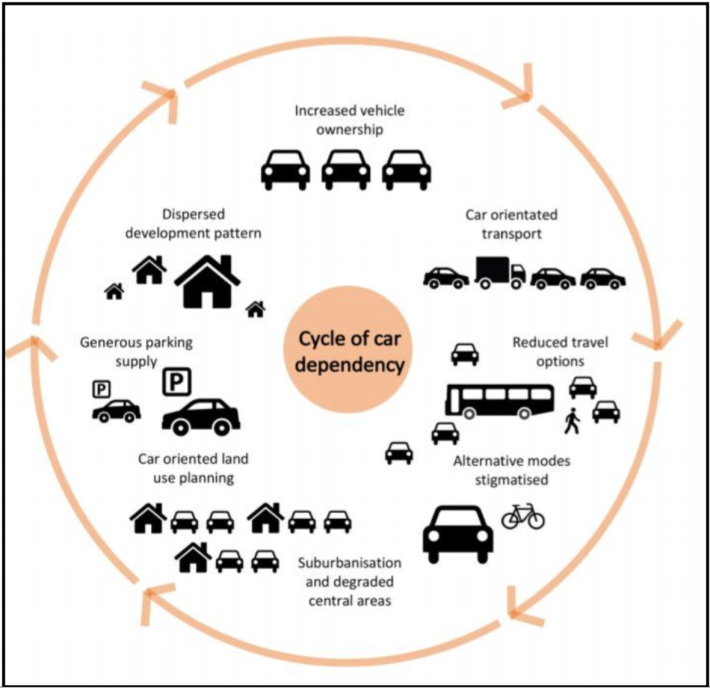

Of course, even without a major public health disaster, our car-dominated places essentially force Americans to maintain a constant state of disaster-preparedness — hemorrhaging money to maintain massive overkill vehicles that can meet our every conceivable mobility need, despite what they cost our families and our society.

But if our cities had networks of strong mass and shared transportation options that could collectively make us feel confident we could get anywhere we need to go with comfort and ease, experts think could help level the playing field.

"Ultimately, how we make our transportation lifestyle choices isn't just about our day-to-day travel," Moody said. "It's about those extremes, those 'What if...' scenarios: 'What if I need to travel somewhere further away for a weekend? What if I get sick suddenly and need to visit a clinic?"

Of course, the lesson of option value isn't that we simply need to write drivers checks to choose more sustainable ways to get around. Moody saysIt's more about making all other modes more convenient and attractive in every way — and that includes land-use reforms that put both basic and desirable destinations within easy reach by foot, bike or transit, rather than simply making that bus ride to your far-flung workplace a tiny bit faster or cheaper.

"In the longer term, it’s really about land-use planning — shaping our transportation systems to be less car-dependent in a comprehensive way," Moody said. "For the majority of Americans, buying a car is a rational choice, and that's because we've built the system to be that way...Our study focused on the value we place on car ownership and car use, but we also looked at how people valued other urban mobility options in their cities, and each of the alternative modes were valued at under a $100 each or less. That’s transit access, ride-hailing, bike share, scootershare — everything. We're a long way from providing a package of transportation alternatives in cities that, together, give consumers the same value as the private car."

Fortunately, we can raise the option value on sustainable travel by improving service quality and coverage — and even truly revolutionary public investments in other modes would be hell of a lot cheaper than continuing to subsidize driving like we do now. And with countless human lives and the fate of the planet at stake, we must do everything we can.