Voters in Austin, Texas might soon approve a historic ballot measure that would radically increase transit access in the capital — and fund an anti-displacement program that could become a model for communities across the U.S. reckoning with how to rapidly expand mobility without destroying vulnerable communities.

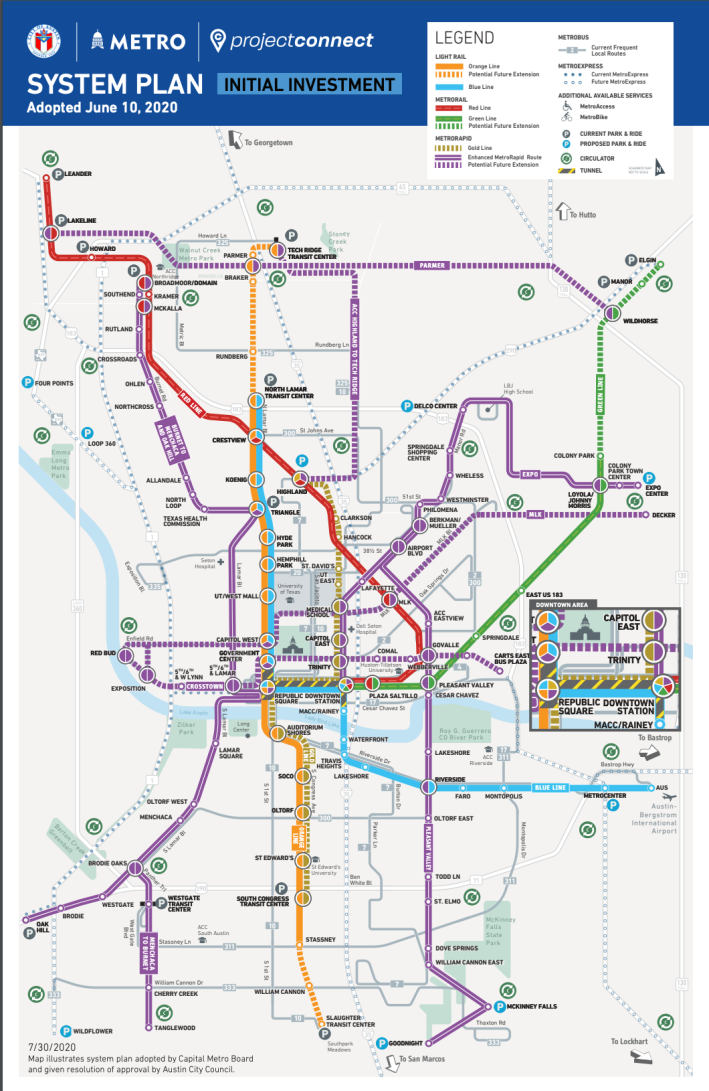

If it passes, the ballot measure known as Project Connect — also known as Proposition A — would permanently increase local property taxes by roughly 4 percent, and would commit the first locally-raised $3.85 billion to a slate of ambitious sustainable transportation projects, which the Violet Crown City anticipates to be matched by $3.15 billion in federal grants. The largest beneficiary of the $7-billion haul would be the city's light rail system, whose mileage would more than double under the plan and connect historically underserved neighborhoods with the downtown core. The bus system would also get a serious boost, including a slate of new rapid transit routes, a fleet of neighborhood circulators, and increased service throughout the network.

The city's bikeshare provider, MetroBike, would also get a gaggle of new e-bike stations at the newly established transit hubs, as well as a new payment system that integrates the bikeshare into the city's transit app.

Altogether, it amounts to one of the largest U.S. transit expansions in recent memory. But the proposition's anti-displacement measures are what's really drawing national attention — and might be most easily replicable by peer cities.

About 7 percent, or roughly $300 million, of Project Connect's initial investment will be devoted to programs specifically designed to keep lower-income Austinites in their homes as property values rise in response to the historic investments. The form those investments remains to be seen; opponents of the measure say that uncertainty is unacceptable, but advocates say it's one of the most equitable aspects of the plan.

"What we heard from communities [during our community engagement process] was, they don’t want a top-down approach," John-Michael Cortez, a City Hall special assistant, said in a presentation for the Eno Center for Transportation. "They want anti-displacement measures that work for the specific people who live in their neighborhoods."

The 'progressive trap': forestalling transit to poor neighborhoods to ward off gentrification

Low-income Austinites have good reason to prefer community-led solutions — and to be wary of a government that has not always prioritized the longevity of their communities over growth at all costs.

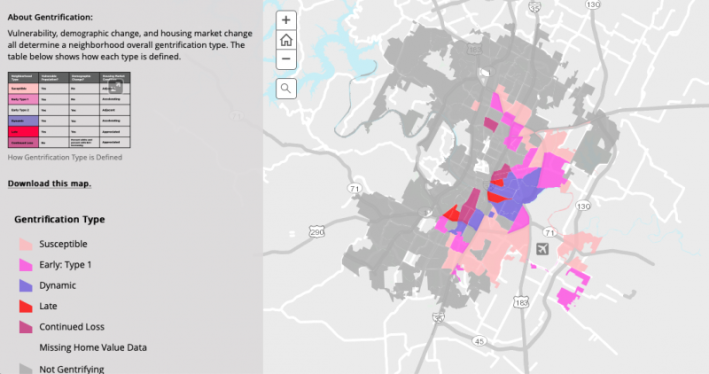

Fueled by the city's booming tech industry and a surprising influx of retirees, Austin is already far and away the fastest-growing metro area in the nation, and also one of the most quickly gentrifying. The region is rapidly getting richer — the share of households earning more than $100,000 rose 52.8 percent between 2010 and 2018 — and overwhelmingly whiter, with historically working-class areas like East Austin experiencing a stunning 442-percent increase in white residents over the same period, as well as a 33- and 66-percent decreases in Latinx and Black residents, respectively. With those shifts have come seismic disruptions in real estate: home prices have risen more than 64 percent across the city since 2010, and rental prices haven't been far behind.

Of course, transit investments don't always translate to landlords jacking up the price of a lease — but high-quality and high-frequency lines like many proposed in Project Connect have been shown to increase home values an average of 24 percent, according to the American Public Transportation Association. On its own, the tax proposed by Prop A probably won't push prices up much — the owner of a $325,000 home will pay about $284 more in taxes per year, one source estimates — and since Austin is heavily populated by renters, the burden will probably fall on the city's wealthier residents. But in a region that's long failed to provide strong mobility choices to non-drivers, low-income Austinites recognize that good transit will feel like a luxury amenity — and they're worried they'll be priced out when the rail lines start getting laid.

"I represent the lowest-income district in the city, and so many of my neighbors say, 'No matter what people see on TV about our neighborhood, the most dangerous thing is just crossing Lamar Boulevard,'" said Austin City Councilman Gregorio Casar, who serves as the chair of the city's housing committee. "And then they say, 'I would love for the city to invest in better public infrastructure and transit — but not tell anybody, because then my rent would go up.'"

But Casar and his colleagues on the city council — all of whom are supporting Prop A — hope that the measure's unique commitment to regionally-sensitive solutions could provide a better path forward. Austin's transit authority, Capital Metro, has committed to appointing a citizens' task force to oversee the distribution of the money, and proponents emphasize that a range of strategies could be eligible funding: some neighborhoods might use the cash to build affordable, transit-oriented housing, for instance, while others could provide critical repair funds to existing low-income homeowners, or legal assistance for those facing title disputes that could uproot them from their residences.

If it works, that approach could be a forward-thinking alternative to more familiar anti-displacement models like inclusionary zoning, which usually requires developers to price a certain percentage of units at a set percentage below the area's median rent; some housing experts argue the policy is well-intentioned, but ultimately incentivizes developers to raise the rent on the luxury units in their portfolio to make up the loss on the affordable apartments, gradually raising the median for the region and defeating the policy's own purpose.

Some progressive transit advocates, though, say that the failures of the past are no reason not to adopt better anti-displacement policies in the future — or avoid building transit altogether. And that's doubly true for Prop A, which advocates say could be key in connecting disenfranchised Austinites to opportunity, while helping them shed the financial burden of car ownership.

"We have to get out of this trap as progressives — because we can fix these legacies of historic under-investment and institutional neglect in our transit network, while also fighting off gentrification," said Casar. "It'd be one thing if this transit plan didn't serve low-income areas. [But] in some parts of my district, we’re going to have some of the best-served stations in the whole network."

When transit needs to stop taking steps and start taking leaps

Not everyone thinks Project Connect is right for Austin.

A political action committee known as Our Mobility, Our Future has drawn donations from major local Republican officials to oppose the measure, and the group has found an odd bedfellow in Progressives Against Project Connect, which staged a protest outside Capital Metro's offices in early October.

Both groups critique Proposition A for devoting too much of its funds to expensive light rail, which the former group argues is fiscally irresponsible, and the latter argues is racist, since light rail, nationally, is disproportionately ridden by white, suburban commuters. The progressive group also is skeptical of Capital Metro's reluctance to commit to specific anti-displacement measures now — especially given the widespread displacement that's followed Austin's transit investments in the past.

“We saw it in 2010 when they started the first light rail; we saw the Riverside master plan come to fruition, and we’ve now seen over 2,000 people have been displaced from the Riverside corridor," activist Susana Almanza told the Austin Bulldog. "And all the affordable apartments are gone and now we only have high-rent apartments in the Riverside Corridor. And that is the first experience that we had with the modern day iron horse, the rail, coming into East Austin.”

In the past, opposition campaigns like these have almost always won out in Austin. In 2000, the first iteration of Project Connect lost by fewer than 2,000 votes, and a slimmed-down version of the measure that would have built just a single rail line lost at the ballot box again in 2014. But advocates think both defeats were, paradoxically, evidence that Austinites wanted even more transit to match the region's astounding population growth — and they weren't willing to settle for less.

"[When we lost in 2000 and 2014], I think that was people saying, 'Well, this project doesn't serve me; it’s not comprehensive enough, and it doesn’t serve enough parts of the city,'" said Cortez. "The community wants us to do something big enough to believe it will work."

Advocates hope that by going big on transit and equity spending, Austin can help the region's mobility landscape finally take the leap it needs, while building a stable tax source that will help both efforts grow for generations to come. And they may need it now more than ever, as the state's road spending is poised to accelerate — without having to jump through any hoops with voters.

"Yes, Prop A is a lot of money — but Austin's also spending $8 billion on Interstate 35 this year, and there’s no election for that," Casar laughed. "But as soon as it’s transit dollars, the same forces that are fine with spending billions on highway expansion start to scream. ... When you get down to it, [Project Connect] is just money well spent. The parts of our city with the most people of color are going to be getting direct access to some of the highest level of light rail service in the country. Working class people who have been pushed to the edges will no longer be forced to take multiple buses to get into the city core where a lot of them work. Being able to get around town is just so important."