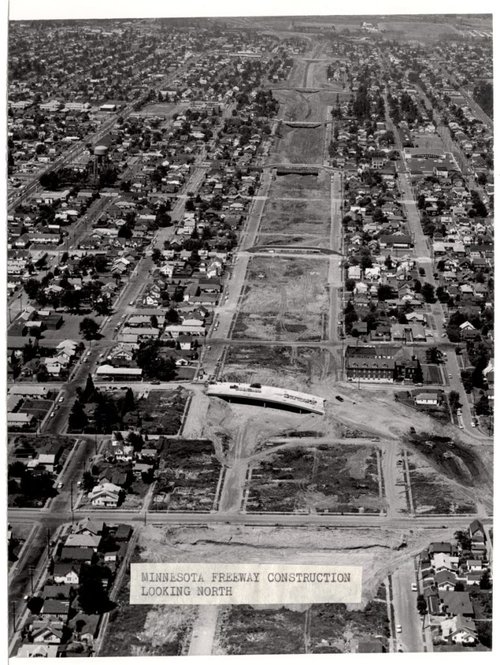

The construction of Interstate 5 in northeast Portland in the 1960s was a classic urban renewal catastrophe. To make room for this highway, the state of Oregon bulldozed hundreds of homes in Albina, a majority black neighborhood, paying owners as little as $50 apiece. The neighborhood was never the same.

In the 1970s, Portland gained a reputation for highway revolts -- successful campaigns to stop the Mount Hood Freeway and tear down Harbor Drive.

But the old political instinct to cram more cars through cities never dies -- not even in Portland. Right now, in 2018, a $450 million expansion of I-5 in the Rose Quarter area is marching forward with the backing of the city's Mayor, Ted Wheeler, and Oregon DOT.

ODOT has taken great pains to present the project as a more enlightened breed of urban freeway widening. The design includes a bicycle bridge and a landscaped cap spanning part of the sunken highway. But make no mistake, the purpose of the project is to add lanes for cars and rework interchanges to pump more traffic through I-5. That's what most of the money is for.

Oregon DOT isn't fooling the "No More Freeways" coalition, which includes the Portland NAACP, Oregon Walks, and the Eastside Democratic Club. They point out that adding highway capacity will exacerbate public health problems and undermine the city's climate goals while doing nothing in the long run to solve congestion.

"The investment is fundamentally antithetical to the Portland region’s values in the 21st century," said Aaron Brown, a leader with the volunteer group.

Widening I-5 won't solve congestion

ODOT wants to add two "auxiliary lanes" to a four-lane freeway segment just over a mile long. The agency says it will shave minutes off rush hour car commutes. But even an analysis commissioned by ODOT found that any effect won't last long: By 2027, traffic congestion will still be significant with the I-5 widening.

ODOT is also considering managing traffic with variable tolls that would rise during peak hours. Advocates want to move forward with the tolling plan without dumping half a billion dollars into highway expansion.

The highway caps are window dressing

City officials including Portland Bureau of Transportation Manager Art Pearce have come out in favor of the project, citing the surface streets and parkings that will be built over the widened highway segment. Pearce said the project will "reconnect the central city."

But Joe Cortright at City Observatory isn't impressed. The highway caps, he writes, are "actually just slightly oversized overpasses, with nearly all of their surface area devoted to roadway."

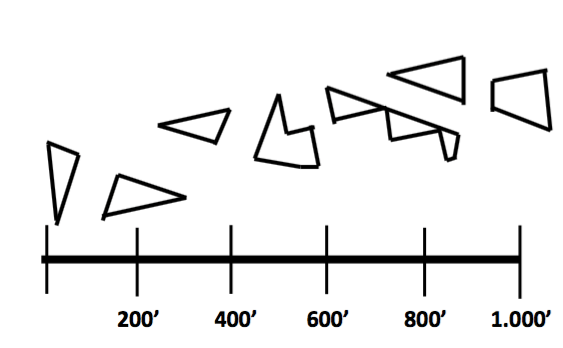

Local advocate Jim Howell created a visualization to show how disconnected the new park spaces over the highway will be.

Other streets should be much higher priorities for safety improvements

ODOT also claims that this segment of I-5 should be rebuilt for public safety, saying it's one of the most crash-prone corridors in the state.

That argument is deceptive, says Kristin Eberhard at the Sightline Institute. There have been two fatalities in the project area in recent years, she notes, and neither could be attributed to freeway design: In both cases, drivers struck homeless men walking on the highway. The high number of crashes reported by ODOT are mostly minor fender benders.

Meanwhile, Portland's arterial streets really are in dire need of safety improvements. There are roughly five times as many serious crashes on these major surface streets as there are on the city's freeways.

If ODOT genuinely wanted to improve safety, it could devote $450 million to support Portland's Vision Zero program instead of a highway widening.

"They are spending half a billion nominally to improve safety but it’s just a guise for improving traffic," said Cortright.

The project severs one of Portland's most important bike routes

Bike traffic is growing at an impressive rate on Flint Street, which currently gets around 10,000 bike trips per day. But Flint Street will lose its appeal as a bike route if the I-5 project advances, because it calls for demolishing the Flint Street overpass, severing the street in two.

The new $15 million bike bridge ODOT is proposing to build, meanwhile, is in a less useful location.

"It's symbolic to show that they’re building some bike infrastructure," said Cortright. "It’s not what anyone who wanted to improve bike or [pedestrian infrastructure] in the neighborhood would impose."

What's next

The I-5 expansion is trudging on, with the state legislature beginning to budget for the project last year. But the state will be counting on federal funding too, and the matter isn't settled yet.

ODOT still has to conduct an environmental review before it can access federal funds. In the meantime, the Portland Planning Commission could decide to remove the I-5 widening from the list of projects eligible for federal subsidies. Last year, one commissioner tried to do just that. He was overruled in a tight 6-4 vote.

Advocates like Brown aren't giving up. "It's the last gasp of freeway builders trying to get half a billion," he said.