In the United States, official bicycle safety messaging heavily emphasizes helmet use. In a way, it's worked: American rates of helmet usage are high. But by almost any quantifiable safety metric, the helmet fixation has failed. People bike at low rates in the U.S. compared to international peers, and suffer higher injury and fatality rates per mile of cycling.

It's not a coincidence that bicycling remains dangerous in our helmet-obsessed safety culture, according to University of Heidelberg professor Gregg Culver. Emphasizing helmets as a singular solution to bike safety -- rather than designing streets for safer car speeds or better bike infrastructure -- upholds a political structure that favors "unfettered automobility," Culver argues in an article published this month in the journal Applied Mobilities.

To analyze the attitudes of American public officials toward cycling and bike helmets, Culver conducted a qualitative analysis of official bike-related texts posted online by the planning departments of 25 U.S. cities. His intent was not to single out planning departments, but to use their materials to illustrate broader political dynamics. He determined that American governments have an "exaggerated and arguably misplaced fixation with helmets."

While none of the 25 cities devote especially long tracts to helmet use, all but one (Atlanta) mentioned them. In general, Culver reports, they prioritize helmets over other safety measures in a few key ways.

Helmet use was typically right up front in cities' bicycling materials, mentioned either first or among the first safety measures.

Admonishments about helmet use were also given special emphasis with exclamation points, italics, or other punctuation, while other safety measures were not. The city of El Paso's bike page, for example, warns cyclists to "WEAR YOUR HELMET!"

In official visual representations of cyclists, helmets are a given. "There is a prominent helmet orthodoxy presented in these images which ties bicycle helmets to happy, safe, and responsible cycling," Culver writes. And these images "work to reinforce the unique focus on the bike helmet."

The tone of helmet-related messages also stood out as especially moralizing, advancing the notion "that helmet use is not a legitimate personal choice, but instead is a moral duty for cyclists."

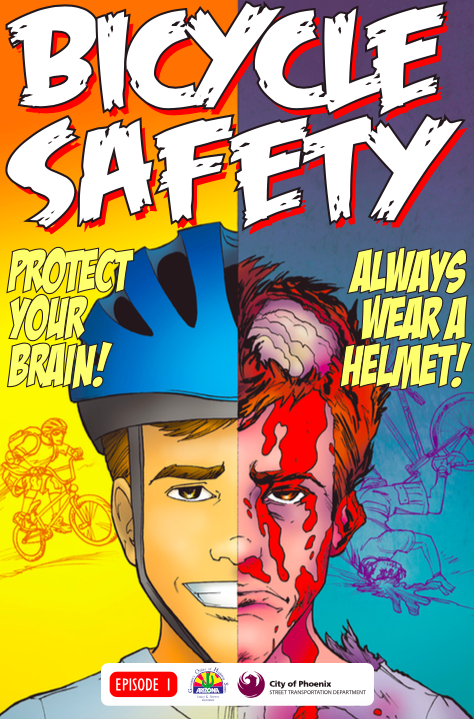

In an extreme example, the city of Phoenix used an extraordinarily graphic comic to illustrate the dangers of not wearing a helmet to children. The images show a cyclist's head split open and brains spilling out on the sidewalk.

Among the 25 cities, only Minneapolis characterized helmet use as a personal choice rather than a moral duty, noting that helmets are not legally required in Minnesota.

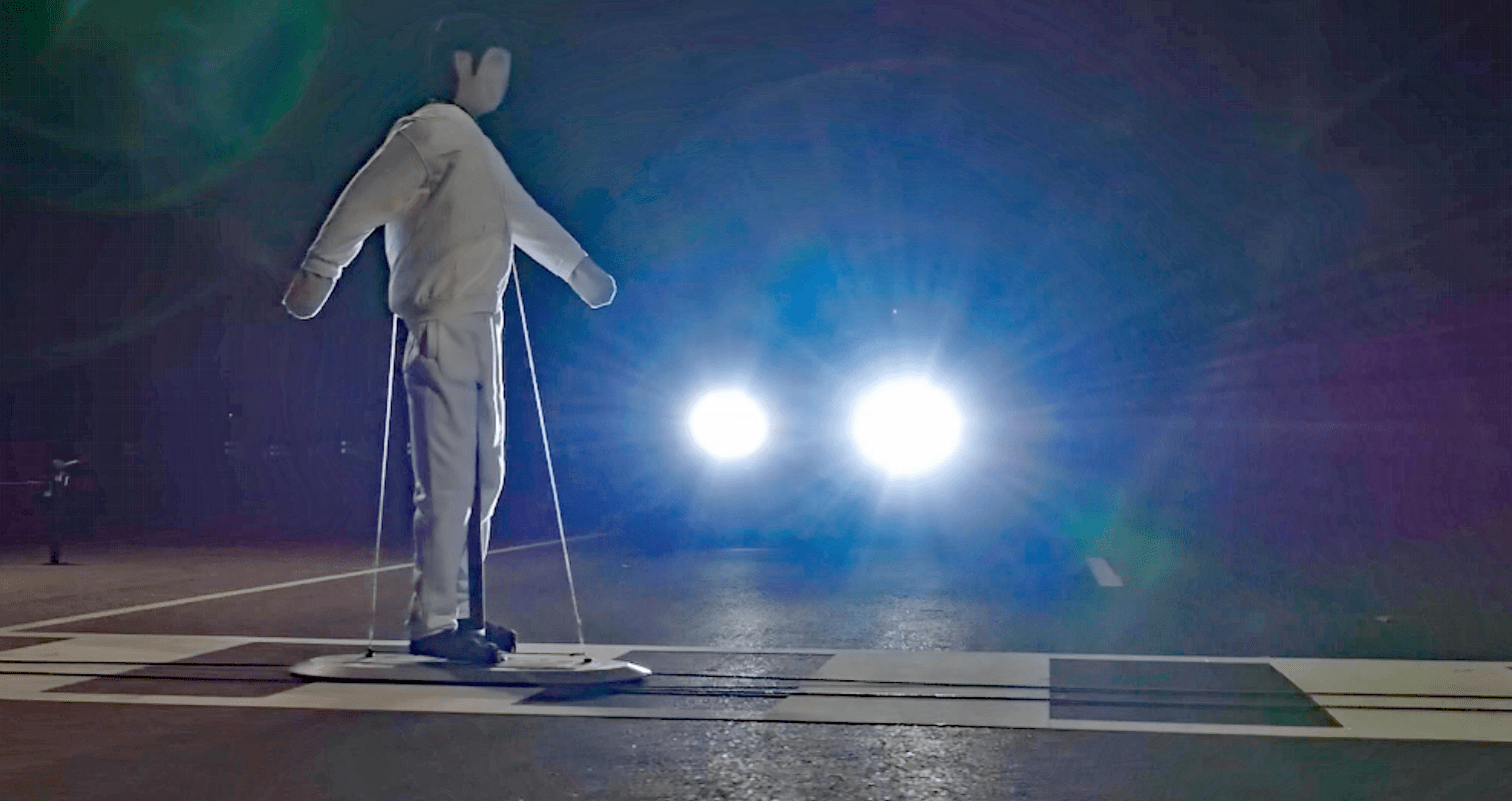

Why such emphasis on helmets? Culver says it's a reflection of the dominant car culture. "The helmet fixation redirects attention away from the overarching problem of vehicular violence, assisting in its denial."

"It redistributes blame," he writes. "By constantly reinforcing the need for cyclists to feel responsible for their own safety (akin to the manner in which jaywalking was invented in the early 20th century), this helmet fixation serves to redistribute blame back onto the victim of vehicular violence."

But Culver did observe some progress in the messages cities put out. He reviewed 20 cities in 2015 and 25 cities in 2017. During those two years, he noticed some cities shift from "more aggressive admonishment and threat of violence to more mild forms of admonishment and suggestion."

In the 2017 review, Boston, Detroit, and San Francisco all prominently displayed photos that included some bicyclists not wearing helmets. Since some of the photos appeared to have been staged, Culver determined that city officials are not as determined to present helmet use as a moral imperative.