Last week, the engine on one of Boston's Orange Line trains overheated and ignited some trash, filling traincars with smoke. Passengers broke windows to escape. Three people were hospitalized for smoke inhalation.

The scare focused attention on long-standing maintenance problems for the T: It's underfunded, upkeep is falling behind, and the quality of service is suffering. Orange Line trains, many of which are three decades old, were in line for replacement later this year. Not soon enough to prevent last week's meltdown.

The MBTA is mired in debt and has a $7.3 billion repair backlog. Following the Orange Line debacle, Mayor Marty Walsh called for a new funding source.

"The problem we have is a problem of literally decades of disinvestment," former Massachusetts DOT director Jim Aloisi told Streetsblog.

The MBTA operates the nation's fifth-largest transit system, serving about 1.3 million trips per day. And ridership has been growing rapidly.

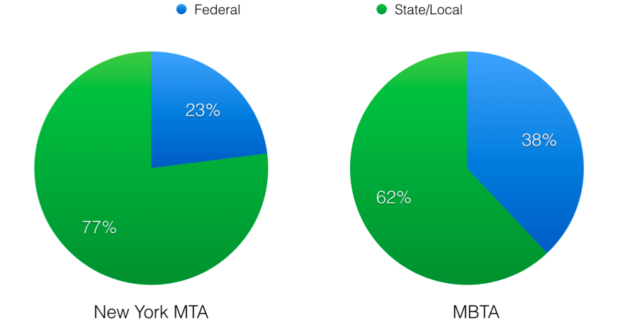

But state and local support for the MBTA is far below what peer agencies receive, according to TransitCenter, leaving the agency at the whim of federal funding sources. Compared to New York's MTA, for example, the share of the agency's capital budget that comes from federal sources is nearly two-thirds higher. If state and local support for MBTA capital expenses were proportional to the MTA, it would add $3 billion to the agency's five-year capital budget.

While funding issues may not account for all of the MBTA's troubles, they explain a lot. And the origins of the problem go back a long way.

An internal MBTA report from 2009 said the agency was "born broke" and remains stuck in a "financial quagmire." In 2000, the state legislature passed a law called "Forward Funding" that took the MBTA off the state's books and established a separate funding stream -- a one-cent, statewide sales tax. As part of the transition, $3.3 billion in debt was transferred from the state to the MBTA.

Revenue from the sales tax barely grew in the 2000s, averaging about a 1 percent annual increase, compared to 6.5 percent in the 1990s, according to the report. Short of funds, the MBTA delayed maintenance and refinanced its debt, in some cases trading lower principal payments for higher rates.

By 2015, 22 percent of the agency's budget was going to debt service. In other words, nearly a quarter of the MBTA's operating budget could not be spent on providing bus and train service.

The 2009 report called for the state to relieve the MBTA of the original $3.3 billion in debt transferred to its books, about half of which was incurred by transit improvements the state had to build in order to proceed with the "Big Dig" highway tunnel project.

Aloisi thinks that debt relief would be a good start. And some conservatives in the state, like the Pioneer Institute, agree (albeit with a lot of strings attached).

Several governors have come and gone without addressing the MBTA's structural budget problems. And current governor Charlie Baker doesn't seem inclined to take action. After the Orange Line fire, he blamed the mess solely on "protocol issues," not the MBTA's maintenance backlog.

To give the Boston region the transit system it deserves, says Aloisi, the state will have to think bigger. Options like a parking tax or a tax on driving mileage, with revenues devoted to transit, should be considered, he said.

"We have a long way to go in Massachusetts before we have a transportation system that reflects our values and our needs," he said.