In a new report, Highway Boondoggles 2 (the original came out in 2014), U.S. PIRG and the Frontier Group teamed up to profile the most wasteful highway projects that state DOTs are building. Streetsblog will be serializing the case studies in the report. Today, we look at the widening of I-70 in Denver, a project with a potentially high social and economic cost.

The need to tear down the viaduct carrying I-70 through the center of Denver is clear, but widening it while while it undergoes much-needed replacement would waste tens of millions of dollars.

The bridge, which was built in 1964, first had detectable cracks in 1981. Since then, it has required many repairs. A major 1997 project installed rods intended to reduce cracking. In 2005, the weight of vehicles on the viaduct was limited in hopes of extending the bridge’s life.

But the bridge continued to crumble. By 2010, the bridge was considered “structurally deficient,” a federal designation indicating significant problems in its structure. A $30 million maintenance project in 2010 was expected to give the viaduct another 10 to 15 years of service. But just four years later, the Colorado Department of Transportation announced that some of the work done in 1997 was failing. The repairs themselves needed to be repaired.

The viaduct is also an eyesore whose removal has been sought by the local community for many years. Since it was built, neighbors have complained that it divides their community, which is one of Denver’s poorest.

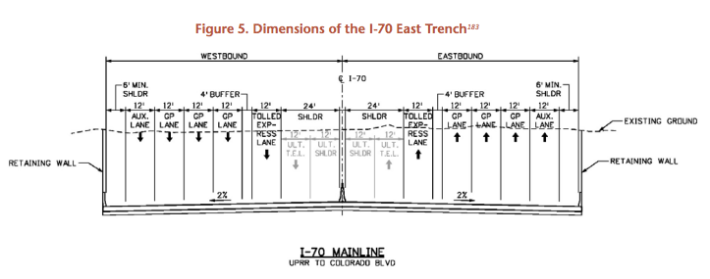

The Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) has proposed replacing the viaduct with a trench for the highway, and partially covering the road with a park. In September 2015, CDOT put out a formal call for private companies willing to finance and build the project. However, CDOT is also proposing to widen the highway.

Originally, CDOT wanted to widen a section of I-70 from I-25 to Tower Road to 10 lanes, up from four- and six-lane segments today, for a total cost of $1.8 billion. Without enough money, the agency scaled the work back to just the area around the failing viaduct, for a cost of $1.17 billion. But its plans to widen the road remain.

There is another major step CDOT could take to reduce the cost: It could decide not to widen the highway. The agency says in an online fact sheet that the additional cost of expanding the highway from eight lanes to 10 would be “very modest." Without detailed evaluations of six- and eight-lane options, cost comparisons have proven difficult.

In 2008, however, CDOT provided the savings associated with a narrower highway. Its original Draft Environmental Impact Statement estimated that building an eight-lane trench instead of a 10-lane one would save $58 million, in part because of reduced need to acquire additional private property on which to dig the trench, but also because of reduced construction costs.

Since then, CDOT has done no additional cost analysis on a narrower project that has been made readily available to the public. Perceived need for highway expansion is already under scrutiny in Colorado. Expert reviewers from the American Planning Association’s Transportation Planning Division suggested in October 2014 that CDOT consider options for I-70 expansion with fewer than 10 lanes, because the state’s review process had not yet done so.

Their report had several criticisms of the existing proposal, including:

- CDOT did not evaluate options with fewer than 10 lanes, instead focusing on one that would “maximize rather than minimize impact on the abutting . . . neighborhoods.”

- In examining the options it did evaluate, CDOT used an outdated traffic modeling system, which had been supplanted in 2010. That old system assumes that people won’t change their travel habits when using routes that are commonly congested, and does not account for the increased traffic created by highway expansion projects.

- CDOT also used an out-of-date model for determining how highway expansion projects drive development and land-use decisions, which in turn influence traffic levels. The department erroneously assumed land-use patterns would remain the same whether the highway was expanded or not; had CDOT properly incorporated the effects of highway construction on development and resulting traffic, it would likely have found worse traffic outcomes than it did.