If sea levels rise just one foot in the Washington, DC, area, nearly 1,700 homes could be lost. Is the region’s transportation planning agency doing enough to stop that from happening? Several environmental and smart-growth organizations in the region are saying no. Seventeen groups have signed on to a letter, being delivered today, urging the agency to take action. The comment period on the agency's latest long-range transportation plan closes tomorrow.

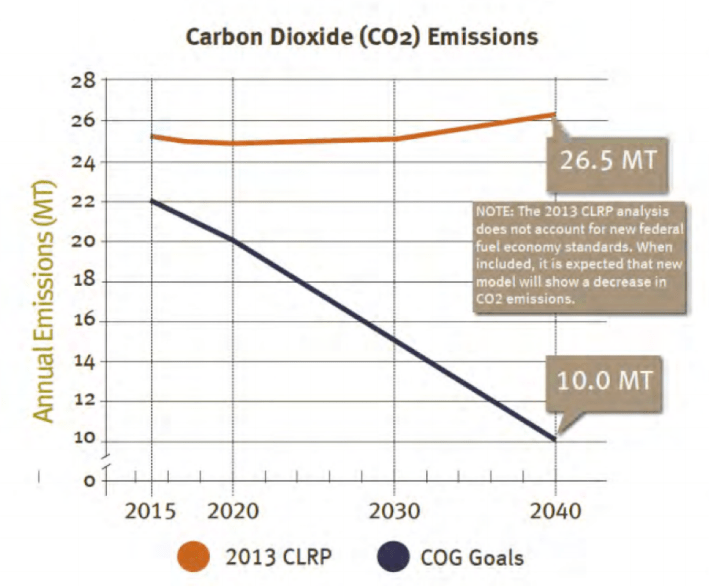

The Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments committed in 2008 to an 80 percent reduction in carbon emissions below a 2005 baseline by 2050. Two years later, the agency added a goal of 20 percent reductions by 2020. But according to its own analysis, the agency’s current transportation plan doesn’t get the job done.

The chart above is from last year’s long-range plan, but the picture hasn’t changed much with this year’s additions. While three of the 11 projects MWCOG has added for 2014 are streetcars and another two are commuter rail, the list also includes a new highway to Dulles airport, an interchange, two road widenings, and the removal of bus-only lanes.

The Coalition for Smarter Growth has asked MWCOG to reopen the plan and shift “significantly more funds to key transit projects,” said CSG Director Stewart Schwartz. He says MWCOG’s long range plans have an “artificial transit constraint,” since the plan can only include projects that have reasonably identified financial resources. However, existing funds could be shifted to transit projects. Schwartz would like to see more money go toward Metro’s Momentum 2025 plan to increase capacity.

But officials at MWCOG say they’re on track. “Climate change goals are a broader perspective than just transportation,” said Bob Griffiths, a 38-year veteran of COG’s Department of Transportation Planning. But even for transportation, they’re “well under” their target levels of ozone and nitrogen oxides, “now and into the future.”

“Because there are currently no conformity standards for the CO2 emissions,” Griffiths said, “we model those as part of our process and make the information available, but the transportation plans are not governed by any CO2 targets.”

Griffiths adds that between now and 2040, it’s projected that three out of five new households and three out of four new jobs will be created in one of 141 identified “regional activity centers,” indicating a concentration of growth and development on less than 10 percent of the total land area in the metro region.

But Schwartz says MWCOG relies too much on increased fuel standards to get them to their emissions goals. The agency has chosen a path that involves significant roadway expansions, which it calls the “aspiration scenario."

“That’s a name we’ve never agreed with because it was not everybody’s aspiration,” Schwartz said. He said it's too heavy on toll roads. "And when you looked under the hood of their analysis, it turned out that the land use and the transit actually provided all of the VMT reduction benefits -- not the toll lanes.”

MWCOG’s Transportation Planning Board -- the federally recognized MPO for the region -- includes officials from the Virginia, Maryland and District DOTs, and Schwartz says those DOTs hold “powerful sway” over the agency’s priorities.

For example, last year, Virginia passed a transportation bill that Schwartz calls a “complicated mess” that was “not good for transit in any way, shape or form.” And while Maryland is a leader on smart growth and sustainable transportation, Schwartz said the state had to cut deals, agreeing to a lot of “questionable interchange projects and highway widenings,” to get votes for increased transportation funding.

“Essentially, all these arrive at COG and are stapled together,” he said.

And while DC’s (now former) planning director Harriet Tregoning encouraged MWCOG to fundamentally reevaluate all its projects, according to Schwartz, the agency almost never takes anything out. Griffiths acknowledged that it’s a rare event indeed.

Seventeen local groups have signed on to a letter, which is being delivered today, urging the TPB to fully disclose the forecasted climate change impact of its 2014 long-range plan and to take action to align the plan with the region’s climate change goals.

“It's not unrealistic for us to achieve bold goals,” they say, noting that 50 percent of all trips in DC are already made by walking, bicycling and transit. The Sustainable DC plan, signed into law in early 2013, set a goal for those modes to account for 75 percent of all trips in the District by 2032. Already, 84 percent of new office construction across the region is within 1/4 mile of a Metrorail station, and vehicle registrations are declining, even as the city adds population.

“There’s no reason why the national capital region shouldn’t lead on this,” Schwartz said.

The comment deadline for MWCOG’s 2014 long-range plan is tomorrow.