Urbanists have long told tales of the success story of Arlington, Virginia. Named a gold-level walk-friendly community by the Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center, this Washington, DC suburb made the smart decision in the 70s to develop along the metrorail line. Because of that, Arlington workers drive alone at a rate 25 percent lower than the region as a whole and take transit more than twice as much. With 11 Metro stations in its jurisdiction, Arlington has more transit ridership than the rest of Virginia combined. Five percent walk or bike to work and carpooling is at three times the regional rate [PDF].

But it wasn’t written on the clouds that Arlington would develop this way. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a community with more obstacles to overcome on its way to smart growth -- and yet, it’s doing it.

Arlington County, at just 26 square miles, is the smallest and densest county in the nation. But it’s far from homogenous. The main-street-style Arlington with wide brick sidewalks, cute cafes and indie bars -- the part people are usually thinking of when they’re lauding the city for its smart development -- exists along the orange line in the dense, mixed-use neighborhoods of Rosslyn, Clarendon, and Ballston. These neighborhoods have taller apartment and office buildings than are allowed in DC, creating a lot of density and a semi-urban feel -- even though those tall buildings line wide arterial streets with lots of fast-moving traffic.

The parts of Arlington just south of the Pentagon, on the blue and yellow Metro lines, don't get as much "walking-gold" spotlight. The Pentagon is the country’s largest office building, and it’s a fortress, disconnected from the community by a mess of highways. The “community” on the other side of those highways is a constellation of shopping malls on either side of a wide arterial road. Still, Arlington’s Director of Transportation Dennis Leach said this area has the best mode split in the county, with 20 percent car-free households, and is making more major infrastructure changes than any other part of the county -- against all odds.

I was there last week on a walking tour as part of the National Walking Summit. Several Arlington planners were on hand to tell us about the streetcars, green bike lanes and café seating we’d soon be seeing along Hayes Street, but for now, it’s a car-centric hellscape. We stood outside a metro station with covered bike parking, yelling over the engine noise of an idling charter bus sitting outside the Fashion Centre shopping mall. Planner Kate Youngbluth admitted the multimodal project in Pentagon City is still in its “ugly duckling phase.”

With a bus network already nearing capacity, the county is building a streetcar system to connect Pentagon City to other nearby communities and counties. They’re upgrading their bus shelters, installing a green bicycle lane, and building a landscaped median on busy Hayes Street. They’ve put in a mid-block crosswalk so people can safely walk between the shopping centers. Army-Navy Drive, which forms a T with Hayes Street between the malls and the highway overpasses, is getting similar treatments. Though the Maryland suburbs are just jumping on the bandwagon now, Arlington was a founding member of Capital Bikeshare.

But the county can only control the streets in its jurisdiction. Jefferson Davis Highway and other state routes follow state guidance on vehicle throughput without much thought for other road users. “Everything that’s ours, we’re going to skinny up and make much pedestrian and bicycle friendly,” said bike/ped planner David Patton. But they can’t do much about the state highways.

The planners said they use the federal governments as a “senior partner” to try to override state mandates. Even the decision to allow on-street parking as a buffer between moving traffic and pedestrians has been a battle with the state. But FHWA isn’t used to building walkable urban environments either, and so the county sometimes has to “clean up” after them too.

The Transportation Security Administration and the Drug Enforcement Agency both have buildings right by the Pentagon City metro station, providing good daytime foot traffic and transit customers but also forcing security precautions that make walkable planning difficult.

Not to mention the 800-pound gorilla just on the other side of Army-Navy Drive: the Pentagon.

“The Pentagon has been not really very supportive of changing how they use their property,” Patton said. "They’ve got vast surface parking lots all over the reservation." The Metro agency, WMATA, would like to create a bus transfer area on one of those parking lots, but that’s a subject of debate.

The Pentagon is in the middle of updating its master plan right now, and perhaps its ocean of surface parking -- on both sides of the highways -- will be revisited. Prof. Mark Gillem, who wrote the armed forces’ smart-growth guidance, says the Pentagon needs to go on a “parking diet” and should start by eliminating the surface lots on the Pentagon City side of the highways. He says those Pentagon City shopping malls provide an elegant solution Pentagon planners haven't yet embraced: The shopping centers and the Defense Department have opposite peak hours, creating a perfect scenario for shared parking.

As the entire military establishment seeks to retrofit its assets for a more smart-growth, transit-oriented, walkable approach, the Pentagon itself is making big changes. Gillem says the Pentagon has improved its Metro access, built a mixed-use retail and dining center inside the building, and resisted pressure to fill in the Pentagon's trademark inner courtyard with offices, preferring to maintain green space.

Despite these forward-thinking updates, however, the military maintains that a Capital Bikeshare station on the Pentagon "reservation" would be a security risk -- which is too bad, since the distance from the Pentagon to the shopping and dining mecca of Pentagon City is ideal for biking. “It’s a five-minute bike ride -- or a dreary 15-minute walk across parking lots,” Patton said. “And they’ve got an instant customer base [for bike-share] in one centralized location. It doesn't get any better than that.”

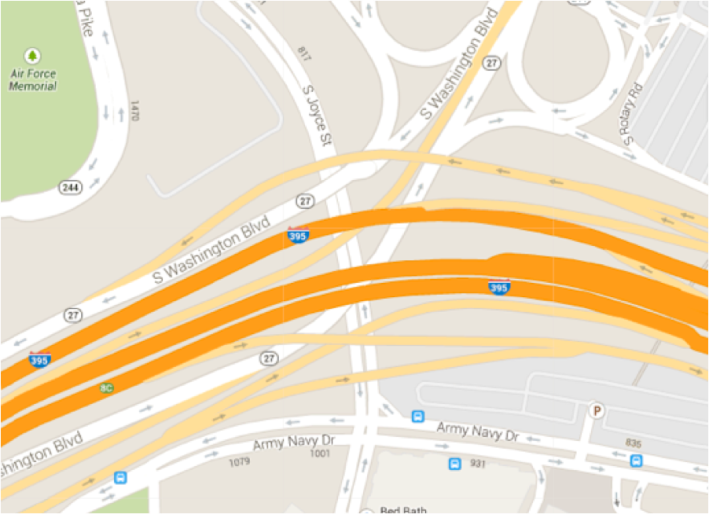

The Pentagon isn’t the only barrier Arlington faces on its journey to walkability. Between the Pentagon City shopping area and Arlington Cemetery is a cluster of no fewer than nine interstate bridges.

Arlington has rebuilt the stretch of Joyce Street underneath all those overpasses to widen the sidewalk, armor the median in anticipation of the streetcar, and install pedestrian-scale lighting. It’s a proud accomplishment, considering that it replaced an unlit four-foot sidewalk separated from 13-foot car traffic lanes by metal crash barriers lined with trash. It’s still a pretty ugly, desolate stretch of underpass, but it’s the bike/ped connection between Pentagon City and the cemetery and the Pentagon itself.

“Where interstates touch urban neighborhoods, they are a challenge, and they create barriers to good walking and biking access,” Leach said. “In almost every city I’ve been in, some of the worst environments are where the interstate ramps touch down and meet local streets. What we’ve tried to do here is at least partially reclaim an environment that may not be a walker’s paradise, but I can tell you as a person who walks a lot and also bikes, I feel a whole lot safer now than I did before.”

A few blocks south of that mess of highway overpasses, Joyce Street becomes a lovely little walkable retail strip, with a housewares store, a Chinese restaurant and a cleaners. Across the street is a massive apartment building, set far back from the street with a moat of parking in between. The county wisely zebra-striped a crosswalk between the two, with shark’s teeth markings and a raised median and yield signs warning drivers to cede the right of way to anyone walking. As we tried to cross Joyce Street, though, the "don't walk" signal lasted so long this entire cadre of planners and walkability advocates ended up crossing against the light.