If there’s a problem connecting workers with workplaces, it stands to reason that there’s a problem connecting workplaces with workers. A new report from the Brookings Institution has teased out the subtleties of this side of the transit/jobs equation.

Last year, Brookings found that, on average, 70 percent of jobs in a metropolitan region are inaccessible to a typical resident via transit. Or at least, it would take over 90 minutes each way to get there.

This time around, Brookings looked at how large a pool of potential employees each employer has access to, assuming those employees would use transit to commute to work. And just as only 30 percent of jobs are accessible to most workers, only 27 percent of workers are accessible to most jobs, they found.

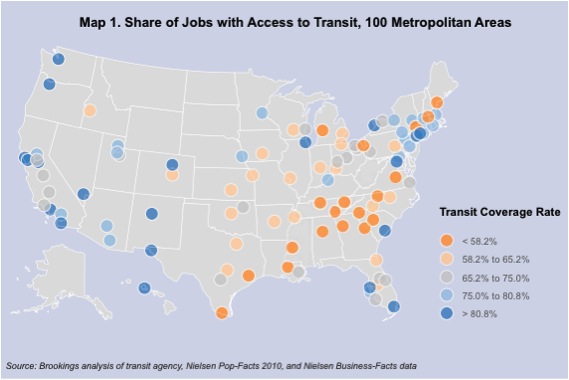

In terms of general access to transit, 70 percent of people in metropolitan areas live in neighborhoods that are served by transit and more than 75 percent of jobs are served by transit. Not surprisingly, the big divide is between suburban and urban locations within those metro areas. In cities, 95 percent of jobs are in transit-served neighborhoods, while in suburbs, only 64 percent of employers have transit service.

The Northeast and the West have better-connected job centers, while the Midwest and the South have more job sprawl and less transit access. In the Northeast, almost 100 percent of city-based employers can take advantage of transit. In southern suburbs, that figure falls to 52 percent.

“The suburbanization of jobs obstructs transit’s ability to connect workers to opportunity and jobs to local labor pools,” the report concludes. “As metro leaders continue to grapple with limited financial resources, it is critical for transit investment decisions to simultaneously address suburban coverage gaps as well as disconnected neighborhoods.” The authors elaborate:

For example, consider the cases of San Jose and Richmond. Both metropolitan areas offer transit service to over 97 percent of city jobs. But while San Jose’s suburban transit routes extend well beyond the city core, offering service to 84 percent of its suburban jobs, Richmond’s suburban routes stop close to the municipal borders, offering service to only 29 percent of suburban jobs. The end result is that San Jose’s overall transit coverage rate ranks fourth and Richmond’s ranks 94th. And Richmond isn’t the only metro that registers this extreme city/suburban dichotomy. Atlanta, Grand Rapids, and McAllen all show near-ubiquitous transit coverage in their primary cities and limited suburban coverage, pushing their overall coverage rates to the bottom quintile.

This report, like the last one, will likely invite observers to wonder whether it’s incumbent on transit systems to undo their hub-and-spoke models and sprawl along with jobs using less efficient service patterns – or whether the solution lies with addressing job sprawl itself. After all, why should struggling public transit systems condone and subsidize employers who chose not to locate near their workers?

Brookings provides a reminder that one way or another, there's a problem that needs fixing: Unemployment is stubbornly high, while in some places there’s a shortage of skilled and educated workers. Clearly, there needs to be a better way to connect jobs and people.

After all, commutes have grown longer and longer over the years, and a continued dependence on single-occupancy vehicles is simply unsustainable. The report says:

The nation’s average distance to work jumped from 9.9 miles in 1983 to 13.3 miles in 2009.6 Meanwhile, as solo drivers topped 74 percent of all commuters, the average number of hours wasted in traffic increased from 14 hours in 1982 to 34 hours in 2010.7 Just as importantly, there is still a sizable portion of Americans that confront longer commuting distances without a vehicle. The costs of owning and operating a vehicle are such that ten percent of American households in the nation’s largest metro areas do not have access to a private vehicle.

Transit can be part of the solution to these problems, and can provide employers with a more reliable way to bring their workers in to work on time every day. But whose job is it to make sure more workplaces are on the transit map? Does the transit system have to build a new line every time some company opens up shop in the exurbs?

Brookings suggests that both public and private sector leaders need to take responsibility for enhancing transit accessibility to jobs. They should route transit to where the jobs are, including in the suburbs, and do a better job of collecting and analyzing data so they can make good decisions, the report says.

But those are all tasks for public officials. What responsibility should private employers take in addressing the accessibility crisis? By locating in a city, an employer will have access to an average of 38 percent of available workers. That same job in a suburb will have less than half the labor pool to choose job candidates from via transit -- just 17 percent of the population.

That doesn’t necessarily mean there’s no transit stop near the employer. But if it’s so far out in the suburban hinterland that it would take the average resident more than 90 minutes each way to get there, it doesn’t count – that’s too long a commute to reasonably ask anyone to undertake.

So in addition to its list of recommendations to public officials, Brookings should add one addressing employers: Locate where your labor pool is. Don’t make them drive alone for 13.3 miles each way to get to work. You’ll suck their souls and waste their money and end up with a less healthy, less reliable workforce that shows up in the morning with a fresh case of road rage (or road fatigue).

Sure, transit agencies need to make sure their expansions are keeping pace with development and that their service is staying relevant. But employers need to realize there are good job candidates out there without cars, and those people won't work at a place that's inaccessible to them.