What happened to the United States over the past several years is most commonly described as a recession. By the technical definition of the word we're two years into a recovery. But it sure doesn't seem that way.

Meanwhile, a growing chorus of intellectual leaders says the country is experiencing something different than a normal cyclical fluctuation: the end of an epoch.

Leading urban thinkers, from Richard Florida to James Howard Kunstler, believe we have reached the limits of our fossil-fueled, double-mortgaged, McMansion-based economy. Relief won't come, they say, until America begins confronting the systemic problems that produced the meltdown, including inefficient and unsustainable public infrastructure investments and housing development.

"What were seeing right now is an inability to look at how we live and how it relates to our problems, and financial problems," said Kunstler Tuesday during a speaking engagement with the Congress for the New Urbanism. "Production homebuilders, mortgage lenders, real estate agents, they are all sitting back now waiting for the, quote, bottom of the housing market to come with the expectation that things will go back to the way they were in 2005."

But despite massive government expenditures to restart the old economic engine driven by suburban homebuilding, recovery is elusive, Kunstler said. The author of "The Geography of Nowhere" and "The Long Emergency" argues that suburbanization has been a multi-decade American experiment, and a failed one.

Kunstler is joined in that perspective by Charles Marohn, the director of non-profit group Strong Towns. A new report from Strong Towns places blame for the lagging economy directly on policies that favor low-density housing, fossil-fuel dependence and publicly-subsidized overbuilt infrastructure.

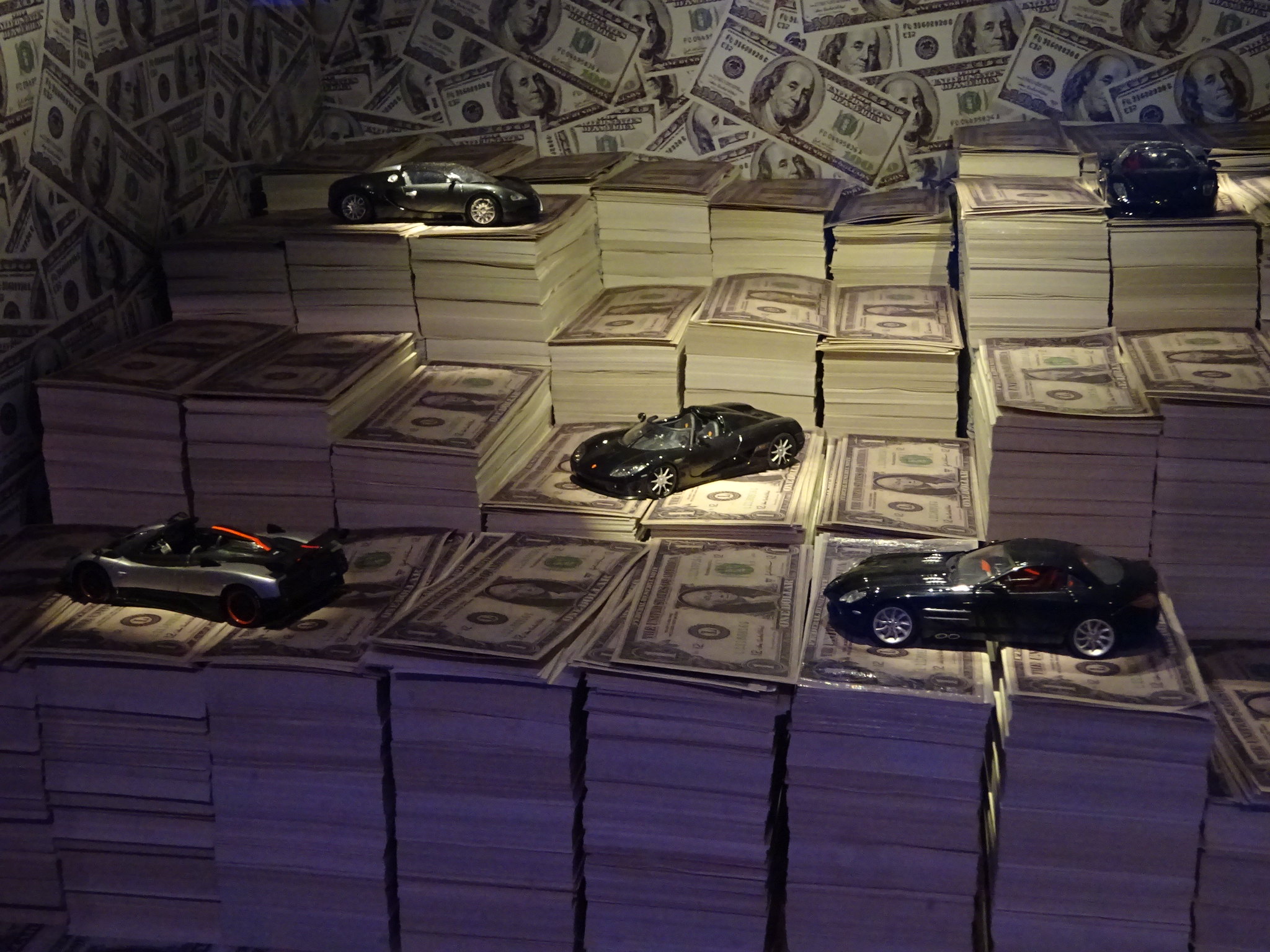

In its new booklet Curbside Chat, Strong Towns asserts that since the 1970s, the suburban growth that powered America's economy operated much like a Ponzi scheme. In towns across the country, politicians traded the short-term payoffs of sprawling development -- namely increased taxes -- for long-term maintenance obligations that are just now coming due. And they're coming up short.

As evidence, the group holds up the fact that the American Society of Civil Engineers estimates the cost of necessary infrastructure maintenance at $2.2 trillion.

"Over a life cycle, a city frequently receives just a dime or two of revenue for each dollar of liability," says Marohn in the report. "In the near term, revenue grows, while the corresponding maintenance obligations —- which are not counted on the public balance sheet —- are a generation away."

The suburban sprawl bubble has now burst, he said.

"Our problem was not, and is not, a lack of growth; Our problem is sixty years of unproductive growth," said Marohn. "The American pattern of development does not create real wealth; it creates the illusion of wealth. Today we are in the process of seeing that illusion destroyed and with it the prosperity we have come to take for granted."

Strong Towns has taken it one step further, outlining 10 development strategies to help get the country back in the black. Among its recommendations are radically altering road and street standards, adopting form-based codes and tailoring capital investment plans to maximize public return on that investment.

"The way forward for our communities is to adopt a set of rational responses to the current situation," says Strong Towns. "This will include shedding some 'dead' ideas from the recent past and embracing a broad set of strategies to start making America’s communities more productive. Local leaders need to position their communities for change if they want to be prosperous in the coming decades."

"The project of suburbia is over," said Kunstler to CNU attendees. "Even though the project of suburbia is still running. There’s no building going on. If you do see construction in these places, it’s just the last twitching."

"We now have to do things differently."